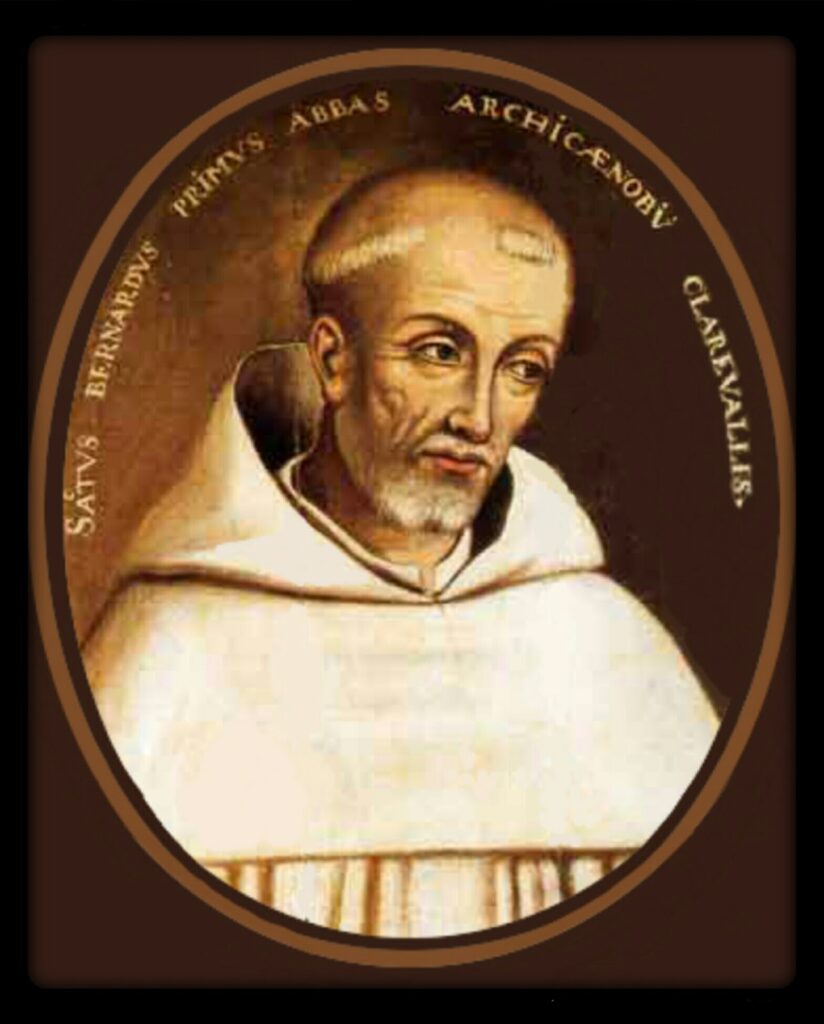

Widely known as “The Passion Chorale,” this profound meditation on Jesus’ crucifixion has guided the devotion of believers for a thousand years! While it has been translated and modified over the years, the original Latin poem has historically been attributed to Bernard of Clairvaux.

He was born in Burgundy, France in 1090. At the age of twenty-five he helped found a monastery which ultimately attracted many others to live in this community of strict spiritual disciplines that led to the formation of the Cistercians. He died there in 1153.

Though many today would disagree with some of his teachings, his devotion to the Lord Jesus was very strong, which led even Calvin to quote from him forty-one times.

Bernard was captivated by Jesus’ person and work, both His compassion and His sacrifice. By his example and his writings, Bernard promoted a deeply experiential expression of Christian faith. The hymn O Sacred Head, Now Wounded, is the best-known of his contemplative writings. The original text included seven stanzas, each focusing on a different part of Jesus’ body … His head, His hands, His feet, His side.

One author has pointed out three dimensions of Jesus’ suffering in the three stanzas which are most commonly used today: the graphic nature of it, the grace that flows from it and the gratitude with which we are to respond when we embrace it.

Graphic Suffering

The words of the first stanza, O sacred head now wounded, with grief and shame weighed down, point us to the reality of Jesus’ physical and emotional anguish. We remember that the Savior was brutally beaten even before He was nailed to the cross. Dr. Luke tells us that even in the Garden of Gethsemane the night before, the Lord sweat, as it were, great drops of blood. It’s not an exaggeration when we sing in stanza one that this execution was “gory.” But we need to remember, too, that the most horrible dimension of Jesus’ suffering was not the physical pain. It was the spiritual agony of taking on Himself the guilt of our sin, and suffering there the undiluted wrath of the Father. After all, as we read in Isaiah 53:10, it was the Father’s will to crush Him as our vicarious substitute. This is the meaning of the New Testament word “propitiation,” that Jesus’ death satisfied divine justice.

O sacred Head, now wounded, with grief and shame weighed down;

now scornfully surrounded with thorns, Thine only crown;

O sacred Head, what glory, what bliss ’til now was Thine!

Yet, though despised and gory, I joy to call Thee mine.

Gracious Suffering

That reality becomes even more evident in the second stanza as we sing, Mine, mine was the transgression but Thine the deadly pain. The cross is a symbol of God’s hatred of sin, hatred under which we deserve to die. But Christ’s pain was for our sakes: What Thou, my Lord, has suffered was all for sinners’ gain. Christ endured the cross to remove our curse (Galatians 3:13) and in so doing show us His amazing grace. Jesus’ death was far, far more than an example of selfless sacrifice for us to emulate. If that were all that was involved, we would still be under the curse of God for our sin. And we would still be incapable of imitating that example because of our sinful nature. No, it was as the Lamb of God that He took on Himself our guilt and our punishment.

What Thou, my Lord, hast suffered was all for sinners’ gain:

mine, mine was the transgression, but Thine the deadly pain.

Lo, here I fall, my Savior! ‘Tis I deserve Thy place;

look on me with Thy favor, vouchsafe to me Thy grace.

Gratitude-Inducing Suffering

In the third stanza, we sing that we can find no words to describe the profound gratitude we should experience as we look upon the bloody sight of our suffering Great High Priest. How can we best thank our dearest friend? The writer picks up on the precious words Christ spoke to his disciples, Greater love has no one than this, than to lay down one’s life for his friends (John 15:13). We plead for divine help in living a life of true love and devotion to our Savior.

What language shall I borrow to thank Thee, dearest Friend,

for this, Thy dying sorrow, Thy pity without end?

O make me Thine forever; and should I fainting be,

Lord, let me never, never outlive my love to Thee.

The Latin text of Bernard’s devotional poem has been translated into many languages. We are especially indebted to Paul Gerhardt whose German text was used, along with the beautiful music of Hans Leo Hassler, by Johann Sebastian Bach in his magnificent St. Matthew Passion. It is from that composition that the hymn has become so widely known and loved.

As one writer has said, “Bernard of Clairvaux’s solemn hymn, O Sacred Head Now Wounded, helps us better understand that the gospel is grounded in Christ’s sacrifice, not in our faithfulness. It also helps us affirm that those who are restored to God through Christ’s sacrifice enter a new friendship with God (“reconciliation”). These themes are not restricted to medieval hymns. But the beauty with which Bernard presents these themes is, needless to say, hard to match.”

If you listen to a recording of the St. Matthew Passion, you will find the chorale interspersed through the music narration.