One of the interesting linguistic “coincidences” of the English language is that we can sing of the “Son” of God also as the “sun” which brings such glorious light into our lives, the two words Son and sun sounding identical, even though spelled differently. At the center of the Christian faith and the Christian life is joyful acclamation of and adoration toward the Lord Jesus Christ. In one of the seven “I Ams” in the Gospel of John, Jesus said, “I am the Light of the World” (John 8:12). The best devotional writing, theological development, and musical praise all speak of His majesty and of our love for and dependence on Him. In other words, as the sun is essential for material life, even more so is the Son essential for spiritual life in more ways than we can ever describe or fully appreciate.

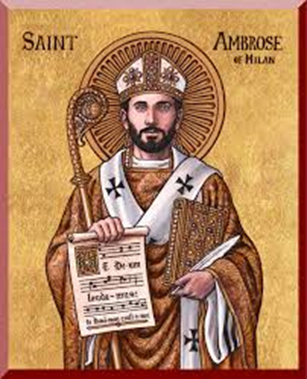

And so it’s not surprising that lyrical poetry in our hymns does sometimes make this connection. One example of that comes to us as a modern adaptation of the ancient writing of Ambrose of Milan (340-397). It is found in our hymnals as “O Splendor of God’s Glory Bright,” whether as a hymn in praise of Jesus Christ, or as a hymn for the morning. The Christian tradition of morning and evening hymns customarily gravitates around prayers for God’s guidance and protection throughout the day or night. In the case of this hymn, these prayers gather around the theme of light, and move from the Son, Jesus Christ, considered here the Light of the World, to the Father who sends the light and from whom all blessings flow, with a passing mention of the Spirit, the third person of the Godhead, in the second stanza. This “theological organization” of the Trinity points, once again, to Ambrose’s goal of theological education in his hymns. The prayers directed towards Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are for illumination, sanctification, protection from sin, and guidance throughout the day’s decisions and interactions with others. These requests create a sung prayer of unique character and flow.

Ambrose, one of the great Latin church fathers, is remembered best for his preaching, his struggle against the Arian heresy, and his introduction of metrical and antiphonal singing into the Western church. Born in Lyons, he was trained in legal studies and distinguished himself in a civic career, becoming a consul in Northern Italy. When the bishop of Milan, an Arian, died in 374, the people demanded that Ambrose, who was not ordained or even baptized, become the bishop. He was promptly baptized and ordained, and he remained bishop of Milan until his death. Ambrose successfully resisted the Arian heresy and the attempts of the Roman emperors to dominate the church. His most famous convert and disciple was Augustine.

Ambrosius (his Latin name) was the second son and third child of Ambrosius, Prefect of the Gauls. At the death of his father in 353, his mother moved to Rome with her three children. Ambrose went through the usual course of education, attaining considerable proficiency in Greek. He then entered the profession which his elder brother Satyrus had chosen, that of the law. In this he so distinguished himself that, after practicing in the court of Probus, the Praetorian Prefect of Italy, he was, in 374, appointed Consular of Liguria and Aemilia. This office necessitated his residence in Milan. Not many months after, Auxentius, bishop of Milan, who had joined the Arian party, died. It was critical that the right person be appointed as his successor. The church in which the election was held was so filled with excited people that the Consular found it necessary to take steps for preserving the peace, and he himself exhorted them to maintain peace and order. A voice suddenly exclaimed, “Ambrose is Bishop,” and the cry was taken up on all sides. He was compelled to accept the post, though still only a catechumen. He was promptly baptized, and within in a week was consecrated Bishop, on December 7, 374.

The death of the Emperor Valentinian I, in 375, brought him into collision with Justina, Valentinian’s second wife, an adherent of the Arian party. Ambrose was supported by Gratian, the elder son of Valentinian, and by Theodosius, whom Gratian in 379 associated with himself in the empire. Gratian was assassinated in 383 by a partisan of Maximus, and Ambrose was sent to deal with the usurper, a piece of diplomacy in which he was fairly successful. He found himself, however, left to carry on the contest with the Arians and the Empress almost alone. He and the faithful gallantly defended the churches which the heretics attempted to seize. Justina was foiled. The advance of Maximus on Milan led to her flight, and eventually to her death in 388.

It was in this year, or more probably the year before (387), that Ambrose received into the Church by baptism his great scholar Augustine, once a Manichaean heretic, who became (after Paul) the greatest theologian of the church for its first thousand years. Theodosius was now virtually head of the Roman empire, his colleague Valentinian II, Justina’s son, being a youth of only 17. In April of 390 the news of a riot when people had gathered in the Thessalonica circus brought to him at Milan. Theodosius decided that a clear demonstration of his anger was required and so the emperor’s troops were let loose. The slaughter was horrible, as 7,000 men, women and children were massacred in three hours. When he presented himself a few days after at the door of the principal church in Milan, Theodosius was met by Ambrose, who refused him entrance until he demonstrated repentance for his crime. It was not until Christmas, eight months after, that the Emperor declared his penitence, and was received into communion again by the Bishop.

Ambrose was indeed a great scholar, an organizer, and a statesman. He was still greater as a theologian, the earnest and brilliant defender of the Catholic faith against the Arians of the West, just as Athanasius was its champion against those of the East. Augustine of Hippo in north Africa (354-530) was drawn to Milan to listen to the eloquent preaching of Ambrose as a way to improve his career as a rhetorician. Listening to the singing of the Psalms in Ambrose’s congregation was one of the factors that played a part in Augustine’s ultimate conversion. Besides being a mentor to Augustine, Ambrose is remembered for his diligent opposition to the spreading heresy of Arianism, a doctrine first attributed to Arius (256-336) in the early centuries of Christianity that subordinated Christ, born at a specific time, to God the Father. One of their “creedal” statements was that there was a time when the Son was not.

As a musician and poet, “The Father of Latin Hymnody” as he has been called, he introduced from the East the practice of antiphonal chanting, and began the task, which St. Gregory completed, of systematizing the music of the Church. As a writer of sacred poetry he is remarkable for depth and intensity. A large number of hymns has been attributed to his pen. Benedictine editors acknowledge twelve Latin hymns as his.

- Aeterna Christi munera.

- Aeterne rerum Conditor.

- Consors Paterni luminii.

- Deus Creator omnium.

- Fit porta Christi pervia,

- Illuminans Altissimus.

- Jam surgit hora tertia.

- 0 Lux Beata Trinitas.

- Orabo mente Dominum.

- Somno refectis artubus.

- Splendor Paternae gloriae.

- Veni Redemptor gentium.

Some traditions credit Ambrose with being the author of the 4th century “Te Deum,” but most regard this attribution as unfounded.

An English translation of “O Splendor of God’s Glory Bright” was made by physician Robert Bridges (1844-1930), one of many hymns proposed by Bridges and several of his contemporaries as an alternative to what they considered unsatisfactory hymnody of the late Victorian period in England. American hymnologists Harry Eskew and Hugh McElrath describe how “in 1899, Bridges prepared the ‘Yattendon Hymnal,’ seen as an alternative to and higher quality hymnal than the earlier Church of England ‘Hymns Ancient and Modern’(1861). The ‘Yattendon Hymnal’championed the restoration of old metrical psalm, chorale, and plainsong tunes.” Faced with the challenge of supplying adequate English translations of these old metrical psalms, chorales, and Latin tunes, Bridges found he had to make new translations or create completely new texts.

Bridges was, according to eminent hymnologist Erik Routley (1917-1982), “a superb metrist and also a cultivated musician.” Because of his mastery of the English language and his talent for verse, “he was uniquely equipped to give [offer these new translations] since (. . .) he could provide that text.” Thus, the “Yattendon Hymnal” does more than simply offer an alternative to what he saw as bland singing, because it “set a new standard of text writing and tune-choosing; his book contains only one or two newly composed tunes, being almost entirely constructed by the pairing of fine but forgotten tunes with appropriate words, new or old.”

Today, many hymnals use a revision of Bridges’ translation, one proposed by American Presbyterian minister and hymnologist Louis FitzGerald Benson (1854-1930). Educated at the University of Pennsylvania, he was admitted to the Bar in 1877, and practiced until 1884. After a course of theological studies he was ordained by the Presbytery of Philadelphia North in 1888. His pastorate of the Church of the Redeemer, Germantown, Philadelphia, extended from his ordination in 1888 to 1894, when he resigned and devoted himself to literary and church work at Philadelphia. He edited the series of hymnals authorized for use by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. His 1915 book, “The English Hymn: Its Development and Use in Worship,” remains one of the classic texts for the study of English hymnody.

Before examining the text of Ambrose’s hymn, this is a good place to include a few comments about Augustine of Hippo (not to be confused with Augustine of Canterbury, who was made archbishop of Canterbury in 597, and is regarded as “the Apostle to the English”), because of the impact made on him by Ambrose of Milan. Here is part of a helpful description from Keith Mathison at Ligonier Ministries.

Augustine was born in A.D. 354 in the town of Thagaste in North Africa to a pagan father and a Christian mother. From these inauspicious beginnings, he would eventually become one of the most influential thinkers in the history of the Church and Western civilization. The ramifications of his debates with the Donatists and the Pelagians are still felt to this day in the Church. His “Confessions” remains a spiritual classic among Christians of widely varying traditions. His magnum opus, “The City of God,” laid down the political and religious foundations for the following 1000 years of medieval history. Those involved in serious theological debate continue to appeal to the writings of Augustine for support.

It is too easy, however, for those of us who live over 1500 years after his death to read his works in a vacuum, without taking into consideration the context in which they were written. We sometimes forget that Augustine was the Bishop of a small port town in North Africa called Hippo Regius and that he was living in a turbulent time in the waning days of the Western Roman Empire. We forget that he had to deal day in and day out with the pastoral pressures and distractions of a sinful congregation. We forget that he lived within a particular cultural, historical, religious and philosophical context that shaped his life and his work. Peter Brown has written a magnificent book that helps us to remember all of these things and to see Augustine within his own cultural context. The original edition of Brown’s biography was published in 1967, and since then it has attained the status of a modern classic ….

Part Four (of Brown’s biography) covers the final years of Augustine’s life from the years 410 to 420. The world changed dramatically in 410 when the barbarian Alaric entered Rome. This was the beginning of the end for the western half of the Roman Empire. The biggest immediate impact that this event had on Augustine was the flood of refugees who fled to North Africa. Pelagius himself, who would later become Augustine’s greatest nemesis, passed through Hippo at this time. Unfortunately (because it would have surely been an interesting encounter), Augustine was away at the time and never met him personally. In these chapters, Brown focuses much of his attention on Augustine’s battles with Pelagius and his followers, and he briefly discusses the later works of Augustine that included such books as the “Retractions.”

It is almost impossible to overstate Augustine’s influence upon the Christian Church. Peter Brown has done the Church a great service by providing the world with a wonderful portrayal of the man and his work.

Returning to the text of “O Splendor of God’s Glory Bright” by Ambrose, we focus on Jesus, the Light of the World about whom John wrote this in the prologue to his Gospel.

In Him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. He came as a witness, to bear witness about the light, that all might believe through him. He was not the light, but came to bear witness about the light. The true light, which gives light to everyone, was coming into the world.

We should always take note of who is being addressed as we prepare to sing a hymn. In this instance, we are singing not just about the Lord Jesus, but to Him. Since He is present wherever two or three are gathered in His name (Matthew 18:19-20), we should be self-conscious of His being in our midst as we are singing to Him.

Stanza 1 announces the theme by describing Jesus as that light, which in its divine glory, even though veiled in flesh (as Wesley wrote in his hymn “Hark! the Herald Angels Sing”), was still filled with the “splendor of God’s glory.” Ambrose used the imagery of the morning sunshine from an eternal dawn, and in the language of the Nicene Creed, as the “Light of light,” meaning the greatest of all light, illumining all days as in a never-ending springtime beauty.

O Splendor of God’s glory bright,

from Light eternal bringing light,

O Light of light, light’s living Spring,

true Day, all days illumining.

Stanza 2 adds to that imagery of Jesus, the Son of God, as the sun of God’s glory brightly shining in our midst and in our hearts. He is the “very Sun of heaven’s love,” shining with warm radiance into every part of our lives and in every one of our days. He does that through His abiding with us by His Holy Spirit, pouring His life-giving ray “on all we think or do today,” and each day.

Come, very Sun of heaven’s love,

in lasting radiance from above,

and pour the Holy Spirit’s ray

on all we think or do today.

Stanza 3 addresses God the Father as the one to whom “our prayers ascend.” As Trinitarians in our faith, we pray to the Father in the name of the Son through the Holy Spirit. Ambrose’s text gives us great confidence in our praying since our heavenly Father is “glorious without end,” and answers us as we plead for His sovereign grace to give us the “power to conquer in temptation’s hour,” something that we recognize we need more and more as we grow older.

And now to Thee our pray’rs ascend,

O Father, glorious without end;

we plead with sov’reign grace for pow’r

to conquer in temptation’s hour.

Stanza 4 refers to more specific ways in which we need the Lord to come to our aid. In this world, and with the remnants of our old sinful nature within, we ask that the Lord will “confirm our will to do the right,” since we too often return to our old ways. “Envy’s blight” tempts us to want what others have, the fires of our faith tend to grow cool, and we fight to be able to “hate the false and love the true” since Satan fills the airwaves with his lies every day.

Confirm our will to do the right,

and keep our hearts from envy’s blight;

let faith her eager fires renew,

and hate the false, and love the true.

Stanza 5 entices us to long for the day when those desires will be most fully granted, when our thoughts that now are too often dark will become “as pure as morning’s ray,” when our faith that now is too often dim will become “like noontide shining bright,” and when our souls that feel often like we are living in the shadows of spiritual reality will be “unshadowed by the night.” What vivid imagery Ambrose has used.

O joyful be the passing day

with thoughts as pure as morning’s ray,

with faith like noontide shining bright,

our souls unshadowed by the night.

Stanza 6 maintains the imagery of light to describe the way we want our days to begin, as we awaken to find that “dawn’s glory gilds the earth and skies.” It should be our morning desire every day that Jesus, the splendor of God’s glory bright,” would arise upon us. Ambrose again uses phrases that are reminiscent of the creeds of the church that identify Jesus as one with the Father, and with the Father’s image conveyed to us in the Son.

Dawn’s glory gilds the earth and skies,

let Him, our perfect Morn, arise,

the Word in God the Father one,

the Father imaged in the Son.

Since the text has been set in Long Meter (L.M.), there are many tunes which can be and have been used, including PUER NOBIS and ROCKINGHAM OLD. Many mainline denominational hymnals (Methodist and Episcopalian) have used the WAREHAM tune, which apparently came from the pen of William Knapp (1698-1768), a parish clerk at the Poole Church in Dorset, England. He has been described as “a typical specimen of the new breed of self-appointed country singing teachers who had little or no formal training.” As these singing teachers were not usually equipped to harmonize their tunes, the version of WAREHAM and other tunes by country singing teachers we find in contemporary hymnals are often later versions, harmonized and/or adapted by others. It must also be pointed out that the books organized by these teachers were a mix of original material and tunes collected from different sources.

Another possibility (found in the “Trinity Hymnal” and the “Trinity Psalter”) is WINCHESTER NEW, from the Hamburg “Musikalisches Handbuch” of 1690 by Georg Wittwe. That melody was also used by John and Charles Wesley for their texts and was reworked by William J. Havergal as a long-meter tune in his “Old Church Psalmody” (1864). Havergal’s version closely resembled its original 1690 form. Named for the ancient English city in Hampshire which was noted for its cathedral, the tune gained much popularity because of its extended use. It is called WINCHESTER NEW to distinguish it from WINCHESTER OLD.

Here is a link to one version of the hymn, as sung using the PUER NOBIS tune.