The times in which we live can be very unsettling. We not only read about things that disturb us. We also experience them that have their origin in our own hearts. Whether it’s worries about our kids or job pressures, financial woes or health fears, relationship breakdowns or job losses, concerns about future threats from hostile foes or car repair bills, they all leave us feeling very out of control and filled with insecurities. A common symptom in such times is a feeling of insecurity and helplessness.

So where do we turn? The world turns to drugs or alcohol, to distractions or denial. But none of those things will deliver us from the deep-seated sense of uneasiness that confronts us. We have a sense that Jesus is the answer (isn’t He ultimately the answer to every question, in some sense?), but how does He set us free? The answer lies at the heart of what it means to be a Christian. It is trusting Him, not just as a vague sentiment, but deeply and closely abiding in Him and seeking to live in obedience to His will.

When in our faith we talk about trusting in Jesus, we mean believing His promises and relying on them. We mean that we are not depending on ourselves, our strength or wisdom, but on His. The beauty and the mystery of this is not that trusting Him will make our problems go away, but that we will not face them alone. He has promised to be that friend that sticks closer than a brother. He has invited us to trust Him and find that He will always be faithful. He has assured us that He will never leave us or forsake us. So when we are determined to trust in Him, we are on solid ground.

For Christians, trust is at the heart of what it means to be saved, to have faith in God. This brief 2001 article from Ligonier Ministries’ Tabletalk magazine is a good summary of what it means to trust in God.

In Biblical terms, to have faith is to trust someone, specifically God. And to trust God basically means to take Him at His word, to accept His promises as valid. This is the attitude for which Abraham is lauded in the New Testament. God promised him descendants, but years went by with no son being born.

Furthermore, Abraham and his wife, Sarah, were old, well past the ages when couples normally have their children. Considering these things, Abraham grew fearful and doubtful, so much so that when God appeared he blurted out, ‘ “Look, You have given me no offspring’ ” (Gen. 15:3a). God responded by specifically stating that Abraham would father a child, and from that child would come a vast nation of people, as many as the stars in the night sky. And on the basis of that word of promise alone—for Abraham had not yet seen any mighty acts by God (with the possible exception of the plagues God brought upon Pharaoh’s house in Egypt in Gen. 12—Abraham “believed in the Lord” (Gen. 15:6a). In other words, he trusted God to do what He had said He would do. He had faith.

Faith like Abraham’s is the key to a relationship with God. Hebrews 11:6 makes this abundantly clear: “Without faith it is impossible to please Him.” Furthermore, the verse goes on to say, in order to come to God a person must believe (that is, he must have faith or trust) that He exists and that He is benevolent. Apart from such trust, we remain lost and dead in sin.

But such faith is not something we produce on our own. The Scriptures tell us that it is given by God. “By grace you have been saved through faith, and that not of yourselves; it is the gift of God” (Eph. 2:8). God gives people of His own choosing the ability to trust Him—for salvation, sanctification, even their next breaths.

There are many 19th century gospel songs about trusting the Lord (“Trusting Jesus,” “Trust and Obey,” “Only Trust Him,” and “Tis So Sweet to Trust in Jesus”). But the church has sung about trusting Jesus for centuries, even if the word “trust” is not in the opening line. In the mid-16th century Joachim Magdeburg (1525-1587), wrote the first stanza (others added to it in the 20th century) of the hymn “Who Trusts in God, a Strong Abode.” This is from the earliest generations of the Reformation in Germany. Remember that Martin Luther had posted his 95 Theses in Wittenberg just eight years before Magdeburg was born.

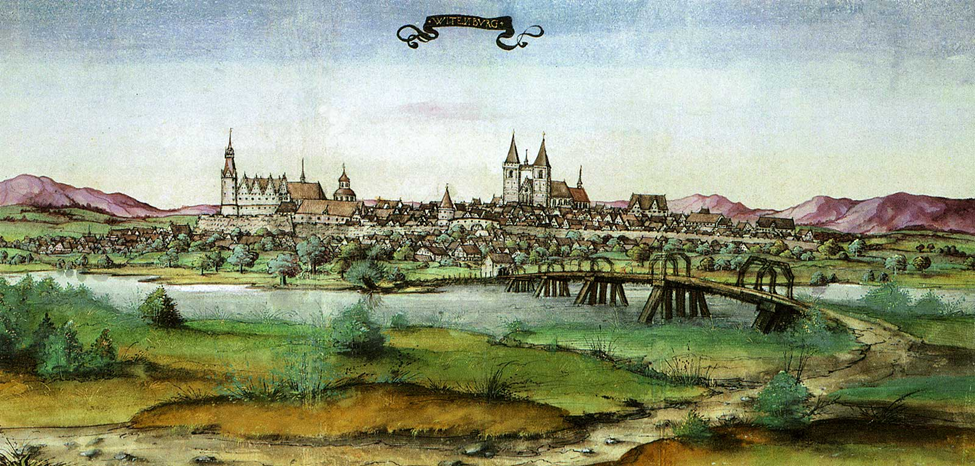

He was born at Gardelegen in the Altmark region of Germany in northern Saxony, the “cradle of Prussia.” He matriculated at the University of Wittenberg, April, 1544, and in 1546 was appointed rector of the school at Schöningen, near Helmstädt, Brunswick. We have no pictures of Magdeburg, but a drawing of the town of Wittenberg of his time is attached with this study.

He became pastor of Dannenberg in Lüneburg in 1547, but being unable to exist on his slender income resigned in 1549, and in the same year became pastor of Salzwedel in the Altmark, an area still very much under the influence of Rome. While Luther did establish some congregations which were separate and independent of Rome, most congregations were still “Roman” in tradition if not loyalty. The change from being of the “one true church, the church of Rome” to something else took literally decades to be anything other than minor and inconsequential. So Magdeburg, having been trained at the epicenter of the early days of the Reformation and a dedicated Lutheran, was banished from the Electorate of Brandenburg. It was because he refused to adopt the Roman ceremonies prescribed by the Act of Interim, that he was banished on Easter Sunday, April 17, 1552. About May of that same year, by the influence of Johann Aepinus, Superintendent of Hamburg, he was appointed diaconus of St. Peter’s Church in Hamburg.

He next got a position at St. Peter’s church in Hamburg, but once again, because of his unwillingness to submit to the Roman church’s proscriptions in various matters was removed. He then went to a church in Thuringia (the area the Bach family was soon to spring from). Again, he ran afoul of the leadership because of his reformist beliefs and was told to leave the area. In those days, if one’s beliefs were unacceptable to the political/spiritual powers he could be forced to relocate or could face imprisonment or worse.

After the death of Aepinus, May 13, 1553, Paulus von Eitzen, his successor, was not so friendly, and when, during the controversy in 1558 regarding Holy Communion, Magdeburg published a tractate without submitting it to be first reviewed by Eitzen, the latter obtained the removal of Magdeburg from his post, May 25, 1558. He then went to Magdeburg to help his friend Flacius as one of the compilers of the Church history known as the “Magdeburg Centuries.” Shortly thereafter he was appointed pastor of Ossmanstedt in Thuringia; but, as a follower of Flacius, was dispossessed in 1562. He then stayed for longer or shorter periods with Count von Mansfeld, Baron von Schönburg and others, until, after the Emperor Maximilian II had once more permitted Protestant preachers in Austria, he was, at Count von Mansfeld’s recommendation, appointed by the commandant of Raab in Hungary as regimental chaplain at Raab in 1564.

After his house there was burnt, at the castle of Gräfenworth (east of Krems), he was assigned to the German-speaking Austrian troops. There he had to contend with the machinations of the Roman clergy, and after joining with nineteen others of the Evangelical clergy in Austria in presenting a Confession of Faith to an Austrian Diet (Landtag), was compelled to leave. In 1571 we find him living at Erfurt. In 1581 he was preacher at Efferding in Austria, but in 1583 was expelled as an adherent of Flacius. He died four years later at the age of sixty-two.

Over the years of his ministry, Magdeburg experienced so many disruptions and controversies, and was forced to move so many times, it is no wonder that he would compose a hymn text like this: “Who Trusts in God, a Strong Abode.” His years were spent in serious devotion to the Lord and in defense of evangelical doctrine, but also in trusting the Lord amidst uncertainty as what the Lord’s design was for him. He trusted the Lord as he was led, step by step, in the path the Lord sovereignly ordained for him. The hymn text is based on the theme of trust as it is found in numerous scripture passages. Among them could be this in Psalm 73:25-26, “Whom have I in heaven but You? And there is nothing on earth that I desire besides You. My flesh and my heart may fail, but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever.”

The hymn lyrics we have today are only a single stanza. We would have expected Magdeburg to have written more. If he did, they have been lost. Two additional stanzas appear in our hymnals today, having come from a 1597 Lutheran songbook by Sethus Calvisius (1556-1615), “Harmonia Cantionum Ecclesiasticarum.” Calvisius, a cantor in St. Thomas Church in Leipzig before Johann Sebastian Bach began at that position in 1723, contributed significantly to the body of Lutheran religious music in the late Renaissance, including a collection of Tricinia (three-voice vocal works in imitative style). But as for the Magdeburg hymn, the composer(s) of those two additional stanzas remain anonymous.

Even within this small example of Magdeburg’s writing, coming after already experiencing so many trials because of his uncompromising commitment to Reformation truths, one can see the bed rock from which his faith rests. In language reminiscent of Luther’s “A Mighty Fortress,” he describes God as a “strong abode.” He then lists what he gains from his Lord: Sweet hope and consolation; our shield from foes, our balm for woes, our great and sure salvation.

We sing an 1863 English translation by Benjamin H. Kennedy (1804-1899), son of Rev. Raun Kennedy, sometime Incumbent at St. Paul’s Anglican Church, Birmingham, and editor of “A Church of England Psalm-Book” 1821). He was born at Summer Hill, near Birmingham and educated at King Edward’s School, Birmingham; Shrewsbury School; and St. John’s College, Cambridge. Graduating with a B.A. in 1827, he was Fellow of his college (1828-1836); Headmaster of Sherewsbury School (1836-1866); and Regius Professor of Greek in the University of Cambridge and Canon of Ely (1867). Having been ordained in 1829, he was for some time Prebendary at Lichfield Cathedral and Rector of West Felton, Salop. He was elected an Honorary Fellow of St. John’s College, Cambridge in 1880.

Kennedy’s translation of Magdeburg’s text was altered in 1864 to the version we now sing by William Walsham How (1823-1897). Born in Shrewsbury, How studied at Wadham College, Oxford and Durham University. He was ordained in the Church of England in 1847 and subsequently served in various congregations before becoming Suffragan Bishop of East London in 1879 and Bishop of Wakefield in 1888. He was called both “the poor man’s Bishop” and “the children’s Bishop,” he was best known during his lifetime for his work among the destitute in the London slums and among the factory workers in west Yorkshire.

He wrote a number of theological works about controversies surrounding the (Anglo-Catholic) Oxford Movement and attempted to reconcile biblical creation with Darwin’s new theory of evolution. He was joint editor of “Psalms and Hymns” (1854) and “Church Hymns” (1871). While rector in Whittington, How wrote some sixty hymns, many for children. His collected “Poems and Hymns” were published in 1886. Among his hymns that remain in common use today are “O Word of God, Incarnate,” “Who Is This, So Weak and Helpless,” “For All the Saints,” “We Give Thee But Thine Own,” and “O Jesus, Thou Art Standing.”

In stanza 1 we sing words that resemble a confession of faith, the biblical faith rediscovered by the reformers, the faith which Magdeburg learned at Wittenberg. The element of trust gives a person great security by abiding in God, dwelling in Him, resting in Him. It reminds us of Psalm 46 which assures us that God is our strength and refuge, our “mighty fortress,” as Luther described Him. And Magdeburg rightly pointed to God, not in a vague sense, but specifically in the person of Jesus Christ. He is the one who promised that as we abide in Him, He also abides in us, even when fears threaten to oppress us. He then is our “sweet hope and consolation, our shield from foes, our balm for woes, our great and sure salvation.”

Who trusts in God, a strong abode

in heav’n and earth possesses;

who looks in love to Christ above,

no fear his heart oppresses.

In You alone, dear Lord, we own

sweet hope and consolation:

our shield from foes, our balm for woes,

our great and sure salvation.

In stanza 2 we sing our profession of faith by articulating more of the specific ways we can feel the insecurities that press on us in this life. Chief among them is the difficulty of living in this fallen world into which Satan has been cast, having been banished from his lofty position in heaven. Until he is finally cast into the eternal pit of hell, his wrath against God is being turned against those whom God loves and the world that God has created. Along with his massive army of demons, he enlists “worldly scorn” to add to our oppression. But even with such potent adversaries as these, we have our Good Shepherd who has promised to remain near us, and whose “strength shall never fail us,” as long as we make Him our “strong abode.” The remainder of this second stanza is clearly drawn from the twenty-third Psalm, with references to His “rod and staff,” and the assurance that though we may suffer for a time, we “shall dwell in the house of the Lord forever.”

Though Satan’s wrath beset our path,

and worldly scorn assail us,

while You are near we will not fear,

Your strength shall never fail us:

Your rod and staff shall keep us safe,

and guide our steps forever;

nor shades of death, nor hell beneath,

our souls from You shall sever.

In stanza 3 we sing triumphantly of our certain victory. This mortal life will trouble us in many ways, but “our feet shall stand securely” because we have made Him our “strong abode.” Temptations will come at us from the world, the flesh, and the devil, but because the Lord is guarding us all the way home, “temptation’s hour shall lose its power.” And until “we stand at Your right hand,” our God will be constantly renewing us in “body soul, and spirit until we stand at Your right hand.” And Magdeburg’s text (though here in this third stanza by some anonymous writer) appropriately concludes with the great Reformation soteriology that our salvation is possible and assured, only “through Jesus’ saving merit.”

In all the strife of mortal life

our feet shall stand securely;

temptation’s hour shall lose its pow’r,

for You shall guard us surely.

O God, renew, with heav’nly dew,

our body, soul, and spirit,

until we stand at Your right hand,

through Jesus’ saving merit.

Among the tunes that have been used for this text, one that works very well is CONSTANCE, written in 1875 by Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900). He was born in London of an Italian mother and an Irish father who was an army bandmaster and a professor of music. Sullivan entered the Chapel Royal as a chorister in 1854. He was elected as the first Mendelssohn scholar in 1856, when he began his studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London. He also studied at the Leipzig Conservatory (1858-1861) and in 1866 was appointed professor of composition at the Royal Academy of Music. Early in his career, Sullivan composed oratorios and music for some Shakespeare plays. However, he is best known for writing the music for lyrics by William S. Gilbert, which produced popular operettas such as “H.M.S. Pinafore” (1878), “The Pirates of Penzance” (1879), “The Mikado” (1884), and “Yeomen of the Guard” (1888). These operettas satirized the court and everyday life in Victorian times.

Although he composed some anthems, in the area of church music Sullivan is best remembered for his hymn tunes, written between 1867 and 1874 and published in “The Hymnary” (1872) and “Church Hymns” (1874), both of which he edited. He contributed hymns to “A Hymnal Chiefly from The Book of Praise” (1867) and to the Presbyterian collection “Psalms and Hymns for Divine Worship” (1867). A complete collection of his hymns and arrangements was published posthumously as “Hymn Tunes by Arthur Sullivan” (1902). Sullivan steadfastly refused to grant permission to those who wished to make hymn tunes from the popular melodies in his operettas.

Here is a link to the music for the CONSTANCE tune, though without vocalists. Only a picture of the page in the “Trinity Hymnal” is visible at the site.