It has been said that the history of the church is the history of martyrdom. The very first promise of the gospel in Genesis 3:15 included the hatred of Satan toward those who belong to God. That hatred burned in Herod’s heart as he ordered the slaughter of the infants in Bethlehem. The Bible records occurrences of this malicious anger over and over again, as when Stephen was martyred, with Saul standing by. Such hatred was poured out on those faithful to the gospel during the Reformation. It was there in the jungles of Ecuador in the martyrdom of Jim Elliot and his companions in 1956. And it was there when newly-wed missionaries John and Betty Stam were beheaded by Chinese communists in 1934.

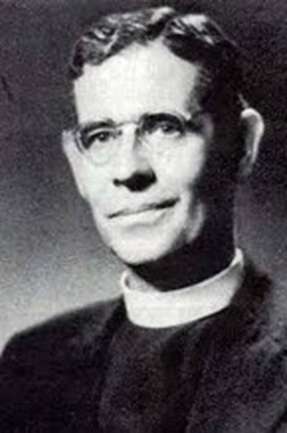

One of the pioneers in missions was Hudson Taylor, who founded the China Inland Mission (CIM) in 1865. Today it is known as the Overseas Missionary Fellowship (OMF). Taylor spent 51 years in China in amazingly fruitful gospel ministry, with hundreds of missionaries motivated to follow in succeeding years. Frank Houghton (1894-1972, pictured here) was an Anglican priest who served with CIM, traveling to China in 1920, first as its executive secretary (director) in China and then as Bishop of Szechwan. Houghton remained there until missionaries were driven out in 1951. He was the author of the hymn, “Thou Who Wast Rich” and also the great missions hymn, “Facing a Task Unfinished.” The Gettys have “revived” that second hymn as a major music project in 2016, featuring it in their concerts and recordings. In his later years, Houghton served in parish ministry at several churches in England.

This is where the stories of Houghton and the Stams intersect. John Stam and Betty Scott met as students at Moody Bible Institute. Betty had grown up in China, the daughter of missionary parents. After her graduation from Moody, she returned to China in 1931, where she again met John in Shanghai in 1932. They sensed God’s call to missions, and after marrying in 1933, were appointed to China by the China Inland Mission. With joy, they anticipated a fruitful ministry, as John had mastered the Chinese language before arriving on the field. They settled in the village of Tsingteh southwest of Shanghai, in a beautiful valley between mountains, accessible only by stone paths through the heights.

They arrived in the village in November of 1934 with their newborn baby girl, Helen. They had been there less than a month when rumors reached the village leaders that marauding bands of communist bandits were in the area. Local officials quickly fled at dawn, but the Stams hesitated, praying that the Lord would show them what they should do. Before they had time to reach a decision, these marauding rogues from the Red Army arrived and cut off all exits. The Stams were taken prisoner and marched 12 miles to the nearby town of Miaoshou. John’s arms were bound behind him, and Betty was transported on horseback, carrying their tiny daughter. Overnight there, John was able to write a short note to mission authorities. It was secreted out, informing them what had happened, and concluded with these words: “My wife, baby and myself are today in the hands of communist bandits. Whether we will be released or not no one knows. May God be magnified in our bodies, whether by life or by death. Philippians 1:20.”

After a night of uncertainty and prayer in a hut, they were pulled out the next morning, stripped of most of their clothing, and marched through the village for all to see. John and Betty were forced to kneel side by side. John started to speak, certainly to point people to the Savior, but before he could do so, his throat was slit. Then the executioner’s sword swung at the back of Betty’s neck, nearly decapitating her. She had wrapped their baby in warm blankets in the hut. Amazingly, the child never cried out until she was found 27 hours later by a local Christian lay evangelist, Mr. Lo, who successfully rescued her. In the blanket, Betty had included a ten dollar bill and some powder for making milk formula, hard to find in that region. Helen wound up being raised by her maternal grandmother until she was five. Following that, Betty’s sister and her husband adopted her and raised her in the Philippines, where they were missionaries. John and Betty’s bodies were retrieved from wooden coffins filled with lime. Mr. Lo had tenderly covered their bodies, and even sewed their severed heads back in place, to await the resurrection.

Word of their martyrdom reached Frank Houghton, who was in an area not yet threatened. He felt the need to travel around to visit and encourage other missionaries serving in China. Reflecting on the suffering of the Stams, he thought about the suffering of the Lord, and particularly the words of 2 Corinthians 8:9, “For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though He was rich, yet for your sake He became poor, so that you by His poverty might become rich.” It was that consideration that led him in 1934 to write the hymn, “Thou Who Wast Rich.” It is a profoundly beautiful meditation on the humiliation (stz 1), incarnation (stz 2), and exaltation (stz 3) of Christ. In that, it follows the pattern of Philippians 2:5-11, how Jesus humbled Himself by becoming a servant and being obedient to death on a cross, and then was highly exalted by the Father and given a name above all names so that at the name of Jesus every knee will bow and every tongue confess that He is Lord. We may not at first think of this as a Christmas hymn, but a second glance will show it to be one of the finest hymns of the season.

We sing the hymn to the tune QUELLE EST CETTE ODEUR AGREABLE (“Whence Is That Goodly Fragrance Flowing”), a 17th century French nativity carol about the shepherds of Bethlehem which John Gay incorporated into his Beggar’s Opera in 1728.

Each stanza points us to the incredible contrast between the heights from which Jesus came to the depths to which He stooped in order to redeem us.

In stanza 1, Houghton writes of the enormous contrast between His riches and His poverty. He exchanged thrones for a manger, sapphire courts for a stable floor. No one else in all of human history has ever come from possessing such extravagant riches to embrace such abject poverty. And why? “All for love’s sake.”

Thou who wast rich beyond all splendor,

All for love’s sake becamest poor;

Thrones for a manger didst surrender,

Sapphire paved courts for stable floor.

Thou who wast rich beyond all splendor,

All for love’s sake becamest poor.

In stanza 2, Houghton writes of the enormous contrast between Jesus’ eternal divine nature and status and His stooping to take on human nature, and even taking on the guilt and punishment of our sins. But by stooping that low, He has raised us all the way to heaven. And why? “All for love’s sake.”

Thou who art God beyond all praising,

All for love’s sake becamest man;

Stooping so low, but sinners raising,

Heavenward by Thine eternal plan.

Thou who art God beyond all praising,

All for love’s sake becamest man.

In stanza 3, Houghton writes of the enormous, incomprehensible love that is Jesus’ very nature, a love “beyond all telling.” And this divine Savior and King is also Emmanuel, God with us. What is his goal? “Make us what Thou wouldst have us be.” And for what purpose? That we would bow in worship before Him. That will be our everlasting joy.

Thou who art love beyond all telling,

Savior and King, we worship Thee.

Emmanuel, within us dwelling,

Make us what Thou wouldst have us be.

Thou who art love beyond all telling,

Savior and King, we worship Thee.

Here’s a beautiful anthem arrangement of the hymn by Lloyd Larson.

Here’s a re-telling of the story of the Stam’s martyrdom.