Why do we sing in our worship services? Congregational singing is something that is unique to Christian worship, in contrast to pagan religions, where worshippers are primarily silent observers in the presence of leaders, or carrying out personal ritual acts of devotion. For us, do we sing just because we enjoy it? Is it that it makes worship more emotionally rich? Is it that music drives the words deeper into our soul? Is it because it enables us all to unite together in worship? Is it that when we sing, we are imitating God the Creator as we create music with our voices? Is it that it creates an environment that will attract unbelievers to come and experience the presence of God?

Yes, all those are a part of it. But isn’t the primary reason we sing that God has commanded that we do so? That is certainly evident when we read (and sing!) the Psalms, all of which are songs, and which contain numerous references to singing to the Lord our Creator and Redeemer, as something which He enjoys. After all, He is the one who designed music itself, as well as the voices and instruments we use in singing. But more than that, we sing now because when we are home in glory, we will forever be joining with the saints in the songs of heaven. So we’re practicing now for our eternal vocation! We find that beautifully shown to us in the book of Revelation, where we are given glimpses of heaven itself. And with our imagination, from the verbal descriptions, we can almost eavesdrop to hear the songs being sung there right now.

And what a sound that must be! The voices of myriads and myriads of angelic voices joining with the countless billions of saints of all the ages gathered in concentric circles around the throne of God, with the Lamb, and before the sea of glass. In Revelation 4 and 5 the Apostle John described what he saw and heard. That vision afforded him a glimpse into what is going on in the presence of God right now, and will continue into eternity as we who know Christ will be privileged to be among that number.

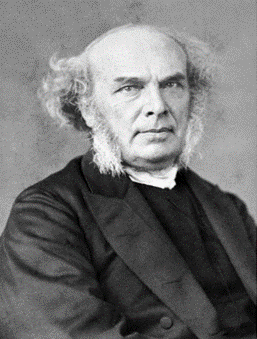

And what are they singing? The same thing we should be singing now. “Worthy is the Lamb!” And as they are ascribing blessing and honor and glory and power to the Lamb on His throne, so should we. That’s what Horatius Bonar (1808-1889) has enabled us to do with this hymn: Blessing and Honor and Glory and Power. An older brother of Andrew Bonar, they grew up in Edinburgh’s high school and also the university there. It was at that university that Horatius came under the influence of Thomas Chalmers, one of his teachers, a leader in the Free Church of Scotland after the doctrinal controversies that led to division in the famous Disruption of 1843. At that time, one-third of the ministers and churches in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland left in protest against the increasing liberalism of the state church, and began the new evangelical Free Church.

Bonar’s ministry began in 1837 when he was ordained as pastor of the church in Kelso on the Tweed. He preached with fervor and unction, and in house-to-house visitation proved himself the comforter of the sorrowful, and guide of the perplexed. In 1839 the Free Church of Scotland sent a commission composed of four ministers, of whom Horatius’ brother Andrew Bonar and Robert Murray McCheyne were the younger members, to visit the principal centers of the Jews in Europe and Palestine. (Andrew Bonar wrote a marvelouos biography of McCheyne.) It aroused widespread interest and Horatius Bonar also visited Palestine in 1856. This visit to Palestine seems to have given occasion for his hymn, I Heard the Voice of Jesus Say. It was while they were there that the famous revival in Dundee broke out, and was energized by McCheyne’s preaching and Bonar’s encouragement.

Bonar remained at Kelso for 28 years, before moving to Edinburgh in 1865, where he continued to minister till his death as pastor of the famous Chalmers Memorial Church, named after his university professor, who had become a patriarch for the Free Church. In 1883, he was elected as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church. Bonar had great interest in prophecy related to Christ’s Second Coming. From 1848 to 1873 he served as editor of a prophecy journal and then for the “Christian Treasury” from 1859 to 1879. He was passionate about revival. He and his brother, Andrew, defended Dwight Moody’s evangelistic ministry in Scotland and authored several excellent works on revival. Throughout his ministry, he was a powerful soul-winner.

He was a prolific writer of hymns, composing more than 600, fourteen of which are included in the PCA/OPC Trinity Hymnal. Among them are I Was a Wandering Sheep; Thy Way, Not Mine, O Lord; Here, O My Lord, I See Thee Face to Face; A Few More Years Shall Roll; Not What My Hands Have Done; and O Love of God, How Strong and True. He died in Edinburgh, July 31, 1889, and was buried at the base of Colton Hill, where he lies with his kindred, near the house of the reformer John Knox. At his funeral no word of eulogy was offered. No better eulogy could be offered than that of the rich legacy of hymns he has left to the household of faith.

In stanza 1, we repeat the very words of heaven’s chorus, with the seven qualities ascribed to Him (in a book filled with sevens!). And we sing these to Christ as the conqueror who has won the battle that results in His being given “the kingdom, the crown, and the throne.”

Blessing and honor and glory and pow’r,

wisdom and riches and strength evermore

give ye to Him who our battle hath won,

whose are the kingdom, the crown, and the throne.

In stanza 2, we sing that all of creation echoes that exuberant praise. It extends to the heavens and rings the earth, and even inanimate creation reflects His greatness. And what is the message they broadcast? Jesus’ glory, fame and power. Words fail us to fully exhaust how great are those divine qualities.

Soundeth the heav’n of the heav’ns with His name;

ringeth the earth with His glory and fame;

ocean and mountain, stream, forest, and flow’r

echo His praises and tell of His pow’r.

In stanza 3, we rejoice that there will be no end to this praise that fills creation. These themes will ever ascend from earth to heaven (our singing), and will ever descend from heaven to earth (the angels’ and saints’ singing). The theme continues to be the same … that He is worthy because of His glorious victory which heaven celebrates.

Ever ascendeth the song and the joy;

ever descendeth the love from on high;

blessing and honor and glory and praise-—

this is the theme of the hymns that we raise.

In stanza 4, we once more announce the glory of the Lamb. We imagine ourselves among the Palm Sunday crowd as well as with our robes in heaven. And the theme is sharpened to focus on the greatest reason for our praise … that He was slain, dying in weakness, but rising in power. This is hymnody at its best, exalting the Savior!

Give we the glory and praise to the Lamb;

take we the robe and the harp and the palm;

sing we the song of the Lamb that was slain,

dying in weakness, but rising to reign.

Here you can hear the first and last stanzas as they are sung.

The tune most associated with this text is O QUANTA QUALIA; its name is taken from the first line of the Latin text by Abelard. The melody first appeared in the Paris Antiphoner, 1681, and was harmonized by John B. Dykes in 1868 for Hymns Ancient and Modern, 1868 (Young, 1993, 535).

Peter Abelard was born in Pallet, France, in 1079 and died in Priory of St. Martel, France, in 1142. At a young age, Abelard showed an unusual capacity for knowledge. He soon became a lecturer at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Although many students flocked to Abelard because of the grace and simplicity of his lectures, his rationalistic views brought him into conflict with many of his colleagues.

Abelard’s life took many twists and turns because he was a priest who fell in love with Heloise, the niece of Canon Fulbert of Notre Dame. When the two could no longer hide their affair, they fled to Brittany, France, where they privately married and had one son. When Abelard and Heloise returned to Paris, Canon Fulbert hired men to emasculate Abelard. After this, Heloise became a nun; and Abelard, a monk. In fact, it was for Heloise’s Convent of the Paraclete, founded at Nogent-sur-Seine in 1129 that Abelard wrote “O Quanta, Qualia Sunt Illa Sabbata.”

Finding a place at the Abby of St. Denis, Abelard resumed teaching and again attracted crowds. St. Bernard of Clairvaux instituted a trail for heresy based on Abelard’s Theologia. He was condemned for heresy by the Council of Soissons in 1121 and by the Council of Sens in 1141 and was forced to cease teaching. He appealed to Rome; unfortunately, he died on his way there. He and Heloise are buried together in the Cemetery of Père-la-Chaise, Paris. This storied romance has been the subject of numerous novels and plays (Glover, 1994, vol. 3A, 311); (Young, 1993, 714) .

John Mason Neale’s (1818–1866) translation of Abelard’s text appeared first in 1854 for the Hymnal Noted. Neale was an Anglican priest, scholar, and hymn writer. His contribution to hymnody in the nineteenth century is vast. Neale is primarily known for his translations from Latin and Greek sources into English. Neale is the original author or translator of over 350 hymn texts.