One of the greatest, and most under-appreciated, benefits that God has given us as redeemed, adopted believers is the spiritual nourishment for our souls in the Lord’s Supper. The first Sunday in October is a good time to remind ourselves of that, since this day is so widely observed as World Communion Sunday. What a wonderful foretaste that is of the wedding supper of the Lamb (Revelation 19:6-9) when, as come to the Lord’s Table with the knowledge that we are united in that event on the same day with our brothers and sisters in every place in this wide world. Every time we celebrate the Lord’s supper, our pastors remind us that we are actually coming into the presence of the Lord who is the one who not only instituted this sacrament, but is actually spiritually present to nourish our souls. And on this day our celebration extends around the world with our brothers and sisters who are coming to the same table.

The Protestant Reformation forcefully rejected the Roman Catholic error of transubstantiation, which continues even today to teach that, by the authority of the priest, the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Christ. The essence of the error is that in so doing, Jesus is sacrificed over and over again every time the Mass is celebrated. That means that the payment for sin achieved by His death on the cross was insufficient to atone for our sins. These repeated sacrifices in the mass in Roman Catholic churches are necessary to complete the payment required by divine justice. And this is in direct contradiction to the multiple Scriptural assurances that “Christ died once for all” (Romans 6:10), something we celebrate in song with the hymn “Jesus Paid It All.”

In rejecting the error of transubstantiation, Reformed believers do not reduce the Lord’s Supper to a mere memorial, a dramatic way of being reminded of Jesus’ death as the all-sufficient atoning sacrifice to cover our sins. No, we rejoice at every opportunity to come to the table to actually be fed, not physically, but spiritually. We don’t believe the Scripture allows us to think that Jesus dies over again each time for our sins by the elements becoming His body and blood. Rather, we believe that Jesus is truly present spiritually, and truly provides nourishment for our souls in a unique way in this sacrament. And we believe that this is different in essence from the nourishment we receive from the Word of God read and studied and preached. As the sixteenth century Scottish pastor Robert Bruce said, we don’t get a better Jesus in the sacrament, but we get Jesus better!

When it comes to our Lord’s Day celebrations of the Lord’s Supper in worship, we have an abundance of hymns from which to draw in our singing. Our hymnals will always have a section of hymns specifically for communion. But we also find appropriate hymns in the hymnal sections on the death of Christ and on His fulfilling the office of priest. Think of such hymns as “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross,” “O Sacred Head, Now Wounded,” “Alas, and Did My Savior Bleed,” “At the Lamb’s High Feast We Sing,” and “Amidst Us Our Beloved Stands.” We would not think of minimizing the importance and value of solid expository preaching on communion Sundays. But should not our services also include a substantial number of Scriptures and hymns?

One of the musical treasures with which we ought to be more familiar (it’s found in more than 100 different hymns!) is the marvelous Lutheran communion hymn, “Soul, Adorn Thyself with Gladness,” written in 1653 by Johann Franck (1618-1677), and sung along with the tune, “Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele,” written in 1649 by Johann Crüger (1598-1662). Both of these men have contributed substantially to our treasury of great Christian hymnody. They both lived through the horrors and suffering of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). During those years, as Catholic and Protestant armies moved back and forth across Germany, conquering and then leaving destruction as they fled, one third of the population of the country died from battlefield injuries or the plagues and famines that followed the conflict. The many hymns of that period reflect an amazing depth of dependence on the Lord coupled with an almost unbelievable degree of joy in the midst of all that anguish.

That joy is wonderfully evident in this hymn. It draws us away from the troubles of this world and opens our eyes to the blessings that Christ gives us in the sacrament. He invites us, in the words of one translation, to “Leave behind all gloom and sadness, Come into the daylight’s splendor, There with joy thy praises render Unto Him whose grace unbounded Hath this wondrous supper founded.” Crüger’s bar form melody has been described as joyful and dance-like. It avoids the funereal tone that sometimes characterizes Reformed observances of the Lord’s Supper. This is dance music for a feast! Many composers have set it for choir or organ. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote a chorale cantata based on the hymn, “Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele” (BWV 180) in 1724. And he composed an organ chorale prelude based on this melody, to be played during communion (BWV 654) in a setting that adorns the melody, as the title suggests, with elaborate ornamentation.

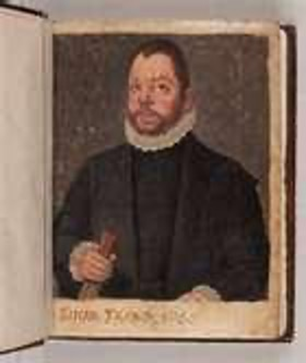

Johann Franck was born at Guben, Germany on June 1, 1618. After his father’s death, in 1620, his uncle by marriage, the Town Judge, adopted him. On June 28, 1638, he matriculated as a student of law at the University of Königsberg, the only German university left undisturbed by the Thirty Years’ War. He returned to Guben at Easter, 1640, at the urgent request of his mother, who wished to have him near her in those times of war during which Guben frequently suffered from the presence of both Swedish and Saxon troops. After his return from Prague, May, 1645, he commenced practice as a lawyer. In 1648 he became a burgess and councilor, in 1661 burgomaster, and in 1671 was appointed the deputy from Guben to the Landtag (Diet) of Lower Lusatia. He died at Guben, June 18, 1677.

As a hymn writer he holds a high rank and is distinguished for his genuine and firm faith. In his hymns we find a wonderful personal, individual tone. That is especially evident in the longing for the inward and mystical union of Christ with the soul, as in his 1655 composition, “Jesus, meine Freude” (“Jesus, Priceless Treasure”). And as with so many Lutheran hymns from this period, as well as with the later hymns of pietism, we are almost stunned by the richness of the soul’s deep, intense love for the Lord Jesus. This will become even more evident when the hymn texts are thoughtfully read as devotional poetry.

The music for this hymn comes from Johann Crüger. He was born in 1598 near Guben, Prussia, Germany. His education included the study of theology at the University of Wittenberg. He moved to Berlin in 1615, where he published music for the rest of his life. In 1622 he became the Lutheran cantor at the St. Nicholas Church. In addition to his writing of hymn tunes, which includes the music for “Now Thank We All Our God,” (he actually wrote no hymn texts), he also wrote music instruction manuals and tirelessly promoted congregational singing. His publication, “Praxis Pietatis Melica” in 1644 is considered one of the most important collections of German hymnody in the seventeenth century. It was reprinted forty-four times in the following hundred years. Crüger also published a complete psalter in 1657. He died in Berlin on February 23, 1662.

As we look at the text of Lutheran chorales like this, we ought to remember that they were all written in German. The translation into English required considerable skill, in both theology and poetry. Many of these are the product of the extraordinarily gifted English hymn writer and educator, Catherine Winkworth (1827 – 1878). Born near London, she was the daughter of a silk merchant, a business which led the family to move to Manchester, where her father had a silk mill. The family later moved near Bristol. It was while spending time in Dresden, she became interested in German hymnody. Around 1854, she published her book, “Lyra Germanica,” a collection of German hymns which she had translated into English. Several additional collections followed in the next few years. According to “The Harvard University Hymn Book,” she did more than any other single individual to make the rich heritage of German hymnody available to the English-speaking world. She died suddenly of heart disease near Geneva on July 1, 1878.

Her translation of Franck’s hymn, “Soul, Adorn Thyself with Gladness,” wonderfully captures the joyful attitude of heart with which we should come to the Lord’s Table. We should do more than just remember with sadness the price He paid by His death. We should also remember with joy the many benefits He has won for us by His atonement. We have forgiveness of sin, adoption as children of God, access to heaven’s throne, the loving presence and guidance of the Holy Spirit every day, and the assurance of eternal life at the moment of our death and in the new heavens and new earth at the time of Christ’s return. While few hymnals contain them all, Franck wrote nine stanzas.

In Stanza 1, we address our own souls, much as we do in Psalm 103. Many have pointed out that we need to preach the gospel to ourselves regularly. And from the very start, the theme of joy dominates the text. If we understand, and believe by faith, what we sing, then there is no room for “gloom and sadness!” How we ought to rejoice that He is willing to dwell with us.

Soul, adorn thyself with gladness, Leave behind all gloom and sadness;

Come into the daylight’s splendor, There with joy thy praises render

Unto Him whose grace unbounded Hath this wondrous Supper founded.

High o’er all the heav’ns He reigneth, Yet to dwell with thee He deigneth.

In Stanza 2, we have the theme of our engagement to Christ as His bride, and look forward to the wedding supper of the Lamb. We sing with delight of the privilege we have to open the doors of our hearts as He knocks and invites us to be joined to Him.

Hasten as a bride to meet Him And with loving rev’rence greet Him;

For with words of life immortal Now He knocketh at thy portal.

Haste to ope the gates before Him, Saying, while thou dost adore Him,

“Suffer, Lord, that I receive Thee, And I nevermore will leave Thee.”

In Stanza 3, we remind ourselves that the most wonderful gift we could ever receive, Christ’s own body and blood, broken and shed for us, is offered to us freely here at the table of the Lord.

He who craves a precious treasure Neither cost nor pain will measure;

But the priceless gifts of heaven God to us hath freely given.

Though the wealth of earth were proferred, Naught would buy the gifts here offered:

Christ’s true body, for thee riven, And His blood, for thee once given.

In Stanza 4, we have the imagery of spiritual hunger, which drives us to the table, where we find such rich food for our souls. The greatest food is the unmerited love of the Friend of sinners, a love which unites us to Him.

Ah, how hungers all my spirit For the love I do not merit!

Oft have I, with sighs fast thronging, Thought upon this food with longing.

In the battle well-night worsted, For this cup of life have thirsted,

For the Friend who here invites us And to God Himself unites us.

In Stanza 5, we use the language of spiritual mysticism in our longing for Jesus, and our sense of awe as we contemplate His love for us, a contemplation that fills our souls with wonder. What incredible power is this which seeks us, forgives us, and joins us to Christ!

In my heart I find ascending Holy awe, with rapture blending,

As this mystery I ponder, Filling all my soul with wonder,

Bearing witness at this hour Of the greatness of God’s power;

Far beyond all human telling Is the pow’r within Him dwelling.

In Stanza 6, we go further into this wondrous mystery. How is it that Christ’s body “remaineth” the same and yet also continually “sustaineth” countless souls? And though this is beyond human reason, we who walk by faith and not by sight are able to see the glorious reality.

Human reason, though it ponder, Cannot fathom this great wonder

That Christ’s body e’er remaineth Though it countless souls sustaineth

And that He His blood is giving With the wine we are receiving.

These great mysteries unsounded Are by God alone expounded.

In Stanza 7, we have sweet terms to speak of our Savior. He is the “Sun of Life,” our “splendor” and “Friend,” the “joy of our desiring” (remember Bach’s chorale setting, “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring”), who inspires our souls. We come to Him for this “blessed food from heaven,” asking that we might be fit partakers of this food.

Jesus, Sun of Life, my Splendor, Jesus, Thou my Friend most tender,

Jesus, Joy of my desiring, Fount of life, my soul inspiring:

At Thy feet I cry, my Maker, Let me be a fit partaker

Of this blessed food from heaven, For our good, Thy glory, given.

In Stanza 8, we recall the sadness involved in this sacrament, recalling Jesus’ suffering. His “love and mercy” drove Him from His “throne in heaven,” dying on the cross “in bitter anguish,” forgoing joy and gladness for our sakes, leading us to praise Him with thanksgiving.

Lord, by love and mercy driven Thou hast left Thy throne in heaven

On the cross for me to languish And to die in bitter anguish,

To forego all joy and gladness And to shed Thy blood in sadness.

By this blood redeemed and living, Lord, I praise Thee with thanksgiving.

In Stanza 9, we look directly at the one who called Himself the “Bread of Life,” the one who invites us to come. Here at the table we find the vast and deep treasure of His love. How amazing that we are invited to be His guest not only here, but eternally in heaven!

Jesus, Bread of Life, I pray Thee, Let me gladly here obey Thee.

By Thy love I am invited, Be Thy love with love requited;

From this Supper let me measure, Lord, how vast and deep love’s treasure.

Through the gifts Thou here dost give me As Thy guest in heav’n receive me.

Here is a rendition with the singing of stanzas 1, 7, and 9.