One place where all true believers should be able to come together is at the Lord’s Table. This can bridge the gap between denominations and ethnicities and social standing, as long as the pure gospel is honored and those who participate in worship in the observance of this sacrament (or ordinance, as some prefer to call it) are true saints (in the biblical sense) who have been “born from above” (John 3:3). One of the things Jesus prayed for in John 17 in His “High Priestly Prayer” (that is the REAL Lord’s Prayer!), was that we might all be one, even as He and the Father are one. The Lord’s Table is a holy place where that prayer, in part, can be seen to be answered,

There have been occasions in which this becomes a visible reality, as in conferences or on mission fields. For some evangelical denominations, their annual national meeting, with representatives from churches across the country, often opens or closes with communion at the table. At the triennial InterVarsity Christian Fellowship Urbana Conference between Christmas and New Years, as many as 18,000 college and university students have shared their love for the Lord and their commitment to Gospel missions by celebrating the Lord’s Supper together before going home. And it’s not unusual in foreign lands for gospel-believing missionaries from multiple sending agencies to join together with nationals for combined worship that includes sharing the bread and wine.

One way in which this is demonstrated and experienced more regularly is on the first Sunday in October, “World Communion Sunday.” It’s a tradition that was begun in 1933 by Hugh Thompson Kerr when serving as pastor of Shadyside Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He first thought of the idea when serving as Moderator of the 1930 General Assembly of his denomination. It was then adopted throughout that denomination in 1936, before spreading to other denominations. Today it is promoted by the decidedly liberal National Council of Churches. While evangelicals will refrain from joining at the table with any who deny the cardinal doctrines of the faith, we can certainly benefit from coming together with like-minded believers at the Lord’s Table.

When we do so, we are not only proclaiming the Lord’s death until He comes (1 Corinthians 11:26), but also proclaiming our true unity in the faith with all who believe in the Lord Jesus as He is presented in the Scriptures. This is a helpful way of reminding ourselves, as well as one another, that the church of Jesus Christ is bigger than our local congregation, or even our denomination. It is at the Lord’s Table that we can live out our profession of faith in the Apostles’ Creed, that we believe in the communion (the unity and fellowship) of the saints.

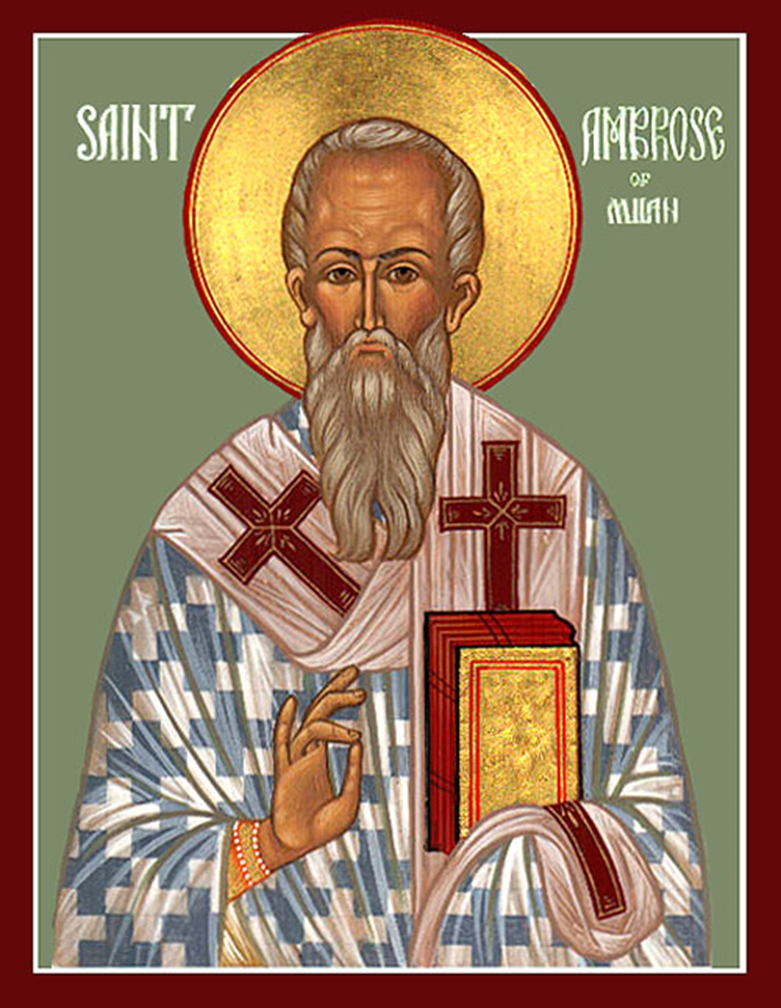

A fine hymn to use on World Communion Sunday is the ancient Latin hymn translated as “At the Lamb’s High Feast We Sing.” This sixth century hymn is known as one of the Ambrosian hymns, so named because of the tradition that the original versions of these were written by Ambrose, Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He became prominent as a fierce opponent of Arianism (which denied the full deity of Christ) and paganism (which dominated secular Roman culture). He is also remembered as an eloquent preacher, whose rhetoric attracted Augustine and ultimately played a role in that great theologian’s conversion and subsequent career as the greatest Christian thinker and writer of the first thousand years of Christendom. Augustine was also drawn to the congregational singing in Ambrose’s church in Milan. While there is no certainty that Ambrose wrote the original text of this communion hymn, the lyrics match the style of some that are known to have come from his pen.

“At the Lamb’s High Feast We Sing” (in its ancient Latin version) was associated with the training of catechumens preparing for baptism. A lengthy and beautiful ceremony began on Saturday evening and lasted throughout the night. During the morning worship the neophytes, vested in white robes, were admitted for the first time to “the banquet of the Lamb.” These white garments were worn during the week following Easter, and on the following Sunday the newly baptized appeared for the first time without their white robes.

And so today the hymn is not only often used on Communion Sundays, but also at Easter, since that is frequently the day new converts (and young people) are welcomed into membership in the church and invited for the first time to come and partake of the elements at the Lord’s Table. What makes the hymn especially wonderful for such occasions is the way it focuses not on us and our profession of faith, but on the Lord Jesus and the victory He has won for all who trust in Him, for all whom the Father has given to Him from before the foundation of the world.

The celebration of the Lord’s Supper was instituted by the Lord Jesus “on the night He was betrayed” (1 Corinthians 11:23), but it was not so entirely new. It was the fulfilment of all that had been symbolized in the Old Testament Passover meal, first commanded at the time of the Exodus. As a perpetual feast, it celebrated the powerful way that God had delivered His people from bondage in Egypt and promised to bring them to the Promised Land. When Christians celebrate this “Paschal Feast” today, they do so by celebrating the fact that Jesus has delivered us from bondage to sin and promised to bring us to heaven’s promised land. As the lamb’s blood was applied to the door of their homes and as they ate the lamb’s flesh that first Passover night, even so the blood of the Lamb of God that was shed for our redemption is applied to our hearts and we commemorate His broken body when we come to the table.

And so as we sing in this ancient hymn, Jesus is not only the Lamb of God, as John the Baptist testified at Jesus’ baptism in John 1:29, and as we read of Him in Revelation 5:6. He is also our Passover Lamb. That is what Paul wrote in the scripture that is the biblical basis for this hymn. “Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed” (1 Corinthians 5:7). The hymn points to Jesus’ broken body and shed blood in the phrase in stanzas 1 and 2, “paschal victim, pascal bread.” Indeed, the text of the hymn connects Jesus to this Exodus event throughout, repeatedly tying the Passover details to the particulars of Jesus’ sacrifice at the cross. And we do so not in a sad commemoration, but also in a joyful feast. Perhaps we ought to make our communion services more of a celebration with music that focuses more on the joy of what He has done for us, rather than just the pain He suffered. After all, this is the feast that is also an “appetizer” of the eternal feast that awaits us when in glory we will celebrate the wedding feast of the Lamb (Revelation 19:9).

The English text most often found in Protestant hymnals today was written by Robert Campbell (1814-1868). Born in Scotland, he attended the University of Glasgow to study theology, but shifted to Scottish law as a profession. He pursued law studies at the University of Edinburgh as a Presbyterian, but joined the Episcopal Church of Scotland, and gave special attention to the education of the children of the poor. In 1848, he began a series of translations of Latin hymns. After 1850 he joined the Roman Catholic Church, perhaps having come under the influence of John Mason Neale and others of the Oxford Movement. His 1849 translation of “At the Lamb’s High Feast We Sing” was included in the 1861 Anglican “Hymns Ancient and Modern” hymnal.

There have been a number of different versions of the hymn, including a larger number of stanzas frequently found in use for Eucharistic services in the Roman Catholic Church. Here are the four most often used in Protestant hymnals (with commentary).

Stanza 1 points us to the broken body and shed blood of our Passover Lamb. With the imagery of Isaiah 1 and Psalm 51, it is the blood of Jesus that has washed us so that though our sins are like scarlet, we shall made white as snow. And what a powerful joining of themes from Hebrews we find in the fact that Jesus is both the victim and also the priest at this sacrifice.

At the Lamb’s high feast we sing Praise to our victorious King,

He has washed us in the tide Flowing from His wounded side;

Praise we Him, whose love divine Gives His sacred blood for wine,

Gives His body for the feast, Christ the victim, Christ the priest.

Stanza 2 points us to the Exodus Passover night when the dark angel of death passed over the homes anointed with blood, sheathing his sword so that we, like Israel of old, can be set free from bondage, and then allowed to go triumphantly “through the wave that drowns the foe,” as happened to Pharaoh’s chariots in the red Sea. Once again we have the joining of the two Hebrews themes of paschal victim and paschal bread.

Where the Paschal blood is poured, Death’s dark angel sheathes his sword;

Israel’s hosts triumphant go Through the wave that drowns the foe.

Praise we Christ, whose blood was shed, Paschal victim, Paschal bread!

With sincerity and love Eat we manna from above.

Stanza 3 points us to our glorious future as our mighty victim from the sky has vanquished the powers of hell. All of that lies beneath Jesus’ feet, and therefore can no longer have an eternal claim over us. As the Puritan, John Owen famously wrote, we can celebrate the death of death in the death of Christ. We no longer fear death and the grave, but look beyond them to the Paradise Jesus has opened for all His saints. We now live in the life and light He has brought us.

Mighty victim from the sky, Pow’rs of hell beneath Thee lie;

Death is conquered in the fight, Thou hast brought us life and light;

Now no more can death appall, Now no more the grave enthrall;

Thou hast opened Paradise, And in Thee Thy saints shall rise.

Stanza 4 points us to the grand celebration of all this at Easter, and thus this is a hymn not only for communion Sundays, but even more so for the grand Lord’s Day celebration of Jesus’ resurrection. We should sing this regularly, since every Lord’s Day is a celebration of the victory won on that first day of the week at the empty tomb. And so, typical of British doxological hymnody, it ends with Trinitarian praise to Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Easter triumph, Easter joy, Sin alone can this destroy;

From sin’s power do Thou set free Souls new-born, O Lord in Thee.

Hymns of glory and of praise, Risen Lord, to Thee we raise;

Holy Father, praise to Thee, With the Spirit, ever be.

In many denominations the lyrics are sung to the SALZBURG tune. The name comes from the Austrian city by that name, made famous by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The tune was first published anonymously in 1678 and then soon thereafter attributed to Jakob Hintze (1622-1702). Subsequent to that, it was harmonized by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). Partly as a result of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) and partly to further his musical education, Hintze traveled widely as a youth, including trips to Sweden and Lithuania. In 1659 he settled in Berlin, where he served as court musician to the Elector of Brandenburg from 1666 to 1695. He is known mainly for his editing of the later editions Johann Crüger’s “Praxis Pietatis Melica,” to which he contributed sixty-five of his own tunes.

In American evangelical churches it is generally sung to the tune ST GEORGE’S WINDSOR, written in 1859 (the same year these Campbell lyrics were written) by George Job Elvey (1816-1893). Most will recognize this as the tune used at Thanksgiving for the hymn “Come, Ye Thankful People, Come.” Born in Canterbury, England, Elvey was a chorister at the cathedral there. He studied at Oxford University and at the Royal Academy of Music. At the age of 19, he became organist and master of the boys’ choir at St. George Chapel, Windsor, where he remained until his retirement in 1882. He was frequently called upon to provide music for royal ceremonies such as Princess Louise’s wedding in 1871, after which he was knighted.

Here is the hymn as sung with choir, organ, and orchestra to the SALZBURG tune.