When we think of Pentecost Sunday, our minds naturally focus on the event as recorded by Luke in the first chapter of the Acts of the Apostles. But we ought also to recall Jesus’ promise to give the Spirit as the “other” comforter in His Upper Room Discourse in John 14 and 16. And we should certainly also turn to the statement in John 20:22, that “He breathed on them and said, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit.’”

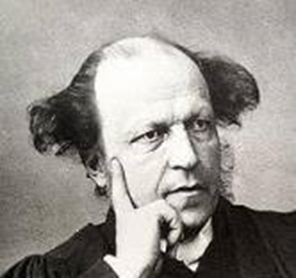

The concept of His breathing matches the Hebrew (ruach) and Greek (pneuma) words for spirit which have the root meaning of wind or breath. And it is that imagery which we find in the hymn “Breathe on Me, Breath of God” by Edwin Hatch (1835-1889), first published privately in 1878 in a pamphlet entitled “Between Doubt and Prayer,” giving it the Latin title of “Spiritus Dei” (Spirit of God). It was later published publicly in 1886 in Henry Allen’s “The Congregational Psalmist Hymnal,” and then republished posthumously by Hatch’s widow in 1890 in “Towards Fields of Light: Sacred Poems.”

Born in Derby, England into a noncomformist family, Edwin Hatch became a minister in the Church of England, and Professor of Classics at the University of Trinity College in Canada. From a young age, Edwin stood out for his work ethic and brilliant intellect. While attending the highly prestigious King Edward’s School, Edwin’s personal teacher made note of Edwin’s independent efforts in education. Whereas most children were eager to finish their lessons for the day, Edwin soaked in all he could, then pursued furthering learning in his own time.

Edwin went on to study at Pembroke College in Oxford. Prior to Edwin’s admission, the college was home to a group of men who called themselves the Birmingham Set. The group’s function was simple: the appreciation of arts and literature. Within the campus library, the Birmingham Set discussed poetry from Percy Shelley, novels from Charles Dickens, arts and architecture from John Ruskin, and so on. Beyond the library, the group was known to venture across Europe, visiting notable churches and medieval sites. Though they were well established when Edwin joined the college, by 1856 Edwin had become the group’s most dominant figure.

While in school, his friends included such stimulating people as Swinburne, Burne-Jones, and William Morris. While an undergraduate, he began contributing articles to reviews and magazines on a variety of subjects. Although brought up as a nonconformist, he became a member of the Church of England in 1853 and became a minister in 1859. After working for a short time with a church in the eastern section of London, he went to Canada from 1859 to 1867, where he was first a professor of classics at Trinity College in Toronto, and later rector of Quebec high school. Upon returning to Oxford, he was made vice-principal at St. Mary’s Hall.

Beyond college, Edwin’s intellectual pursuits burned ever on. College professor, high-school rector, university vice-principle; Edwin was all of these and more. Being a man of God, Edwin was drawn to the study of deep theology, for it combined God and learning. Naturally, he became so well versed in theology that he became a religious lecturer. Of his lectures, he is most remembered for his Bampton lectures; lectures known for profound theological discourse. These lectures, which displayed Edwin at his most studious, were published and translated into various languages. However, the most famous publication of this highly educated man ended up being a prayer of simplest and most humble nature, “Breathe on Me, Breath of God.”

Edwin wrote this hymn in 1878 and kept it private for many years. This adds to the unique nature of the hymn, as it was originally meant only for Edwin and God. As much as Edwin loved complex thoughts and theologies, he understood that at the core of Christianity is something incredibly simple. We are born of the Spirit, as Jesus said in His night-time conversation with Nicodemus, recorded in John 3. But we also live as the Spirit breathes new life into us continually. It is our desire, as Paul often wrote, to be filled with the Spirit, not only in the moment of our regeneration, but increasingly so throughout our lives.

Educated at Pembroke College, Oxford, Hatch ministered in an Anglican parish in the slums of east London before accepting the position at Trinity College in Quebec where he taught classics. After serving as Rector of Quebec High School, he returned to Oxford to become the vice-principal of St. Mary’s Hall, and took several posts including the Bampton Lecturer, Reader in Ecclesiastical History, and the Hibbert Lecturer. Hatch was recognized as an authority on the early church as a result of his Bampton Lectures, “On the Organization of Early Christian Churches,” which were acknowledged by a leading continental scholar on this topic and translated into German.

His erudition, analytical mind, painstaking research work, and strong character gained for him the reputation as a great scholar, but in spite of his scholarship, he maintained a spirit of simple piety. His death occurred at Oxford on November 10, 1889. He authored a limited number of hymns which he did not care to publish. They were printed posthumously by his widow in “Towards Fields of Light” in 1890.

As a hymn for Pentecost Sunday addressed to the Holy Spirit, it is a fitting prayer for the church to sing, asking that He breathe on us to advance the work of sanctification and spiritual usefulness in our lives. Some have questioned whether it is scriptural to sing a song which is addressed to the Holy Spirit. However, since the scriptures are said to be given by inspiration of God, or literally “God-breathed” (2 Timothy 3:16), one could sing this song as a request to God the Father, asking Him to “breathe” on us, figuratively meaning to grant to us those spiritual blessings which are promised to us through the written word. Most of our hymnbooks in the past have avoided songs directed to the Holy Spirit, but recent decades have seen this hymn included as one in the section of hymns to and about the Holy Spirit.

But as we make this request of Him, are we conscious of the fact (and aware of the evidences in our lives) that He has been granting this request from the earliest days of our new life in Christ? In fact, we would not even have this desire if it were not for the fact that He has been breathing on us, creating the desire for His presence and influence. Among the “proofs” that we are born again is this longing for more of His presence and influence on us.

Here are some of the ways He breathes on us.

Stanza 1 mentions new life. When we obey the gospel revealed by the Spirit, we walk in newness of life: Romans 6:3-4. This new life requires that we love what God loves, because the fruit of the Spirit involves love: Galatians 5:22-23. It also requires that we do what God would do, because to inherit the kingdom of heaven we must do the will of the Father: Matthew 7:21.

Breathe on me, Breath of God, Fill me with life anew,

That I may love what Thou dost love, And do what Thou wouldst do.

Stanza 2 mentions purity. In the Sermon on the Mount, the Spirit teaches us to be pure in heart: Matthew 5:8. The pure heart must make its will the will of the Father: Luke 22:42.

And those who have received such a pure heart will also seek to endure whatever may come so that they can be saved: Mark 13:13.

Breathe on me, Breath of God, Until my heart is pure,

Until with Thee I will one will, To do and to endure.

Stanza 3 mentions surrender. As we follow the teachings of the Spirit as found in the scriptures, we demonstrate by our lives that we belong wholly to God: 1 Peter 2:9-10. To do so, we must surrender our earthly part to be crucified with Christ that He might live in us: Galatians 2:20. Then we must let our lives glow with fire for God; the word translated “zeal” literally means “to be hot:” Titus 2:11-14.

Breathe on me, Breath of God, Till I am wholly Thine,

Till all this earthly part of me Glows with Thy fire divine.

Stanza 4 mentions eternal life. Through the power of God’s word, the Spirit tells us of the Lord’s promise that those who come to Him will never die: John 11:25-26. The hope of those who thus come to the Lord is to be permitted to live the perfect life with Him: 1 John 2:25. And in this way, we can share in His eternal glory: 1 Peter 5:10-11.

Breathe on me, Breath of God, So shall I never die,

But live with Thee the perfect life Of Thine eternity.

When a person becomes a Christian, he or she receives the Holy Spirit within. However, each person needs new supplies of the Spirit’s presence and power each day in the struggle to overcome sin and grow in holiness. The Scriptures teach us that we are to be filled with the Holy Spirit. This is not some emotional, mystical event. To be “filled with the Spirit of God” means in a very practical way that a believer has surrendered completely to the Lordship of Christ and sincerely desires to be directed by the Holy Spirit in order to worthily exalt Christ and be an effective representative for God. One of the most compelling evidences of a Spirit-filled life is our consistent, Christ-like daily living. Of course, the only way to be “filled with the Spirit” (Ephesians 5:18) is to “let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, in all wisdom” (Colossians 3:16) because the sword of the Spirit is the word of God (Ephesians 6:17). Hence, the way which we accomplish being filled with the Spirit is in our obedience to what God the Father has revealed to us through Spirit by the word that He caused to be written by inspired apostles and prophets. Thus, we are simply asking the heavenly Father to bestow upon us all the blessings and benefits that He has made available to us through the Spirit’s word when we sing, “Breathe on Me, Breath of God” every day, not just on Pentecost Sunday.

The tune most often used in the U.S. is TRENTHAM, named for a small village in Staffordshire, England. TRENTHAM was composed by Robert Jackson (1842-1914) in 1888 and was originally used with Henry William Baker’s hymn, “O Perfect Life of Love” in the 1888 “Fifty Sacred Leaflets,” though some sources give the date of 1894. It was first used with Hatch’s text in the 1933 “Presbyterian Hymnal” and is now the standard setting for it.

After receiving his musical training at the Royal Academy of Music, Robert Jackson worked briefly as organist at St. Mark’s Church, Grosvenor Square, in London. But he spent most of his life as organist at St. Peter’s Church in Oldham, Lancashire (1868-1914), where his father had previously been organist for forty-eight years. A composer of hymn tunes, Jackson was also the conductor of the Oldham Music Society and Werneth Vocal Society.

Here is a link to a very gentle and peaceful soloist singing all four stanzas.