The hearts of Christians beat with passion for the Lord Jesus, and for the Great Commission. In a sense, that passage at the end of Matthew 28 could be called Jesus’ “last will and testament.” But that wouldn’t be entirely accurate, since He still lives among us and dwells within us. His resurrected, glorified body was received into heaven at His ascension, but He promised that His spirit would be with us to the end of the age. And in issuing this Great Commission, He assured us that we would not be carrying out that commission in our own strength, but by the power of the Holy Spirit.

One of the marks of a healthy church is that there be a widespread missions mentality. This means more than simply assigning a portion of the church budget to support for missionaries and mission agencies. That can and does happen, but then members of the church have little knowledge of it, and receive no encouragement to become emotionally and prayerfully engaged in missions. In contrast, there are churches that promote missions by having a separate missions budget to which people are regularly invited to contribute, by praying for missionaries by name in morning worship, by including brief missions reports in Sunday announcements and monthly newsletters, by holding a missions conference (annually) with guest missionaries speaking to share their ministry reports and visiting at meals and in members’ homes, and by enlisting members to go on mission trips to spend a week or two with missionaries in the field to experience that foreign culture and see first-hand what church planting is all about.

For a church to become more “missions-minded,” there needs to be visible and audible support from leadership, especially from the senior pastor. If he’s not passionate about missions and engaged in missions ministry, there’s not much chance that the members will catch that vision. It’s a vision that is truly there now “at the very top” since we gather to worship the world’s greatest missionary: the one who left His heavenly home to come into a hostile world to bring the gospel that is our one and only great hope. That’s the idea that Margaret Clarkson had in mind when she wrote (and later re-wrote) her classic missions hymn, based on Jesus’ charge in John 20:21, “As the Father has sent Me, even so am I sending you.”

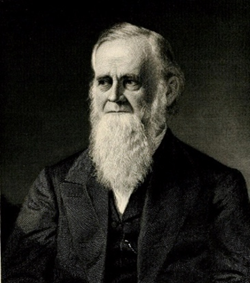

It’s no surprise, then, that our hymnals contain ample resources for singing about the Great Commission and our missions challenges today. Many missions conferences will include the singing of the hymn “Christ for the World We Sing.” It was written on February 7, 1869 by Samuel Wolcott (1813-1886). A Connecticut native and graduate of Yale College and Andover Theological Seminary, he served as a missionary in Syria from 1840 to 1842, where his first wife, Caroline Elizabeth Wood, died. He was forced to return to America because of health problems that arose. On his return to America, he was successively pastor of several Congregational congregations, including time in Belchestown, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island; Cleveland, Ohio; and Chicago, Illinois. He was also for some time Secretary of the Ohio Home Missionary Society. His hymn writing began late in life, but has extended to more than 200 hymns, many of which are still available only in manuscript form.

Wolcott himself described the origin of this hymn in these words. At the time, he was pastor of Plymouth Congregational Church in Cleveland. “The Young Men’s Christian Associations of Ohio met in one of our Churches, with their motto, in evergreen letters over the pulpit, ‘Christ for the World, and the World for Christ.’ This suggested the hymn ‘Christ for the world we sing.’” It was when on his way home from that service that he composed the hymn. This was the first hymn that he had composed, but it has become a standard for missions themes and is found in almost every hymnal today.

He served during the time of America’s Civil War and regularly gave public speeches about the war. His sons had enlisted in the war, including 16-year-old Edward. In 1874, he was made secretary of the Ohio Home Missionary Society and served in that position until 1882. After his first wife died, he then married Harriet Amanda (Pope) Wolcott on November 1, 1843. They had eleven children, one of whom, William Edgar, became a Congregationalist minister, in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Wolcott returned to Longmeadow in 1882, living there until his death on February 24, 1886.

The “modern missions movement” is generally dated from 1793 when English Particular Baptist minister William Carey (1761-1834) sailed to India, after having published his groundbreaking missionary manifesto, “An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens” in 1792. He faced significant opposition among his pastoral communion at home before going, and struggled with major challenges during his years in India. Despite all that, he showed himself to be an amazingly gifted linguist and persevering servant of Christ, and translated the Bible into seven languages for different people groups in India.

But there had been significant earlier missionary efforts prior to Carey, including the church planting ministers sent from Calvin’s Geneva into France and across the Atlantic into Brazil. During the years of the Great Awakening, there were significant Moravian missionary efforts launched into the American colonies. It was Moravian missionaries whose confidence in the Lord during a fierce Atlantic storm aboard ship in 1736 made such a dramatic impact on the as-yet unregenerate John and Charles Wesley.

The surge in missionaries and mission agencies grew in the 1800s to include such names as Adoniram Judson, David Livingstone, John Paton, Amy Carmichael, Alexander Duff, and Hudson Taylor, and sending agencies like the China Inland Mission, Africa Inland Mission, and Sudan Interior Mission, as well as sending agencies in most Protestant denominations. By the end of William Carey’s life, there were only a few score foreign protestant missionaries. By 1900, this had grown to 15,000, and continues to grow today in missionaries sent out (as those challenged from Inter Varsity’s triennial Urbana Conferences).

And the number of Christian martyrs among them has also grown exponentially in the last 100 years, including the five martyred in Ecuador in 1956. Today, including both Catholic and Protestant foreign missionaries, it is estimated that there may be as many as 450,000 career missionaries serving in distant lands. Jesus’ Great Commission has been taken seriously, but there is much more that needs to be done. A passion for Jesus must also include a passion for the lost.

As gospel preaching has spread, English-speaking churches experienced a surge in the writing and singing of what has come to be characterized as “Gospel Hymnody,” with songs like “Victory in Jesus,” “Pass Me Not, O Gentle Savior,” and “Blessed Assurance,” from writers like Fanny Crosby, Frances Ridley Havergal, and Ira Sankey. And there has also been an increase in missions hymns which offer a counterbalance to the more personal gospel songs with their focus on an individual relationship with Christ. Whereas many of these gospel songs, composed on both sides of the Atlantic, viewed Jesus as a personal companion on the journey to heaven, the great mission hymns present Christ as the triumphal monarch who claims all earth as His domain, a vision to be fully realized in heaven as described in Revelation 7:9: “After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands.”

Sadly, in liberal denominations today, it has become the goal that mission hymnody should give way to what some have called “ecumenical” hymnody, hymns from former “mission fields” that can inform and broaden our faith and provide congregational song for the ecumenical church. This usually involves replacing the biblical gospel of salvation from sin through saving faith in Jesus, with a version of the old social gospel of salvation from hunger and injustice and discrimination. Where this has happened, the missionary force is reduced to a much smaller number of volunteers who go overseas as more of humanitarian activists than church planters. Indeed, the foreign missions forces of mainline liberal denominations have shrunk to relatively few. This is all the more reason that we need to maintain and reclaim the great mission hymns of the past for the role they played in motivating those who responded in good faith to Matthew 28 in their day.

Wolcott’s great missions hymn is based not only on that Great Commission in Matthew 28. It also supports Paul’s words in 2 Corinthians 5:19, “in Christ God was reconciling the world to Himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation.” And so we sing, “Christ for the World We Sing.” Wolcott knew his Bible well, as we find direct Scriptural allusions and paraphrases throughout the four stanzas. We especially should notice as we start singing, that each stanza begins with the same phrase, “Christ for the World We Sing.” Hopefully, then, we will sing with that passion in our hearts.

Stanza 1 pictures the world in its spiritually lost condition. It mentions “the poor and them that mourn.” This world is full of sadness and sorrow, but there is something to alleviate it (Matthew 5:4). It mentions “the faint and overborne.” These are the people of this world who are weary and heavy-laden, but again God offers a solution (Matthew 11:28-30). It mentions “the sin-sick and sorrow-worn.” The reason for the sadness and heavy burdens is sin, but there is something that can be done (Romans 3:23 and 6:23).

Christ for the world we sing;

the world to Christ we bring

with loving zeal:

the poor and them that mourn,

the faint and overborne,

sin-sick and sorrow-worn,

for Christ doth heal.

Stanza 2 identifies redemption as the remedy for “the wayward and the lost,” those who are “by restless passions tossed,” but can be “redeemed at countless cost from dark despair.” Jesus Christ came to redeem us from our sin (Galatians 4:4-5). This redemption is available through His blood to provide for the forgiveness of our sins (Ephesians 1:7). The remission of sins made possible by Christ’s redemption is to be preached to all the world (Luke 24:44-47).

Christ for the world we sing;

the world to Christ we bring

with fervent pray’r:

the wayward and the lost,

by restless passions tossed,

redeemed at countless cost

from dark despair.

Stanza 3 points out the need for all Christians to be involved in proclaiming this message to the world. This is work that we all must share (1 Corinthians 15:58 and Galatians 6:7). There will be reproach to bear from those who will ridicule and oppose us and the message we bring (1 Timothy 4:10 and 1 Peter 4:14). That means there will be a cross to bear “for Christ our Lord” (Matthew 16:24 and Galatians 6:5).

Christ for the world we sing;

the world to Christ we bring

with one accord:

with us the work to share,

with us reproach to dare,

with us the cross to bear,

for Christ our Lord.

Stanza 4 sings of the results of our obedience to the Great Commission: our joy over “newborn souls.” Even the angels of heaven are filled with joy over just one sinner who is saved (Luke 15:7). We also need to be happy for those newborn souls, whose days have been “reclaimed from error’s ways” because they have believed inn Christ to be saved through Him and have everlasting life (John 3:16-17). When we do, like Paul we should be inspired with hope and praise that these now belong to Christ and consider them our joy and crown (Philippians 4:1).

Christ for the world we sing;

the world to Christ we bring

with joyful song:

the newborn souls whose days,

reclaimed from error’s ways,

inspired with hope and praise,

to Christ belong.

The lyrics were written to fit an existing tune (ITALIAN HYMN), composed in 1769 by an Italian immigrant to England, Felice de Giardini (1716-1796). Born in Turin, he was a child prodigy. His father sent him to Milan, where he studied singing, harpsichord, and violin, but it was on the latter that he became a famous virtuoso. By the age of 12, he was already playing in theater orchestras. In a famous incident about this time, Giardini, who was serving as assistant concertmaster during an opera, played a solo passage for violin which the composer Niccoló Jommelli had written. He decided to show off his skills and improvised several bravura variations that Jommelli had not written. Although the audience applauded loudly, Jommelli, who happened to be there, was not pleased and suddenly stood up and slapped the young man in the face. Giardini, years later, remarked: “It was the most instructive lesson I ever received from a great artist.”

During the 1750s, Giardini toured Europe as a violinist, scoring successes in Paris, Berlin, and especially in England, where he eventually settled. For many years, he served as the orchestra leader and director of the Italian Opera in London, and gave solo concerts under the auspices of Johann Christian Bach, with whom he was a close friend. He directed the orchestra at the London Pantheon. From the mid-1750s to the end of the 1760s, he was widely regarded as the greatest musical performing artist before the English public. In 1784, he returned to Naples to run a theater but encountered financial setbacks. In 1793, he returned to England with hopes for greater success. But times had changed, and he was no longer remembered. He then went to Russia, but again had little success, dying in Moscow in 1796.

This ITALIAN HYMN melody was originally intended for use with the song “Come, Thou Almighty King” by gospel song composer William H. Doane (1832-1915). “Christ For the World We Sing” seems to have had its first appearance in “Songs of Devotion for Christian Associations,” published in 1870 by Biglow and Main of New York City, NY, and compiled by William Howard Doane.

Here is a link to the hymn sung in congregational Lord’s Day worship.