Suffering is an unavoidable reality in this life for all people, whether Christians or not. It takes many forms, from illnesses and disasters to persecution and old age. We were not designed for pain and sadness, but sin’s curse has brought all forms of sadness and misery into creation. It will not always be so, for Christ’s return will usher in the glorious eternal age of the new heavens and new earth in which, as Revelation 21:4 describes it, “He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, not crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away.” But until then, sorrow will be a part of our lives.

The Bible records every form of suffering that afflicts mankind, from the records of Job’s afflictions at the hand of Satan, to David’s fleeing the jealous anger of Saul, to the martyrdom of Stephen as the as-yet-unconverted Saul stood by. God not only shows us the reality of suffering, He even gives us principles and promises to sustain us when we are struggling and words to sing in Psalms that show us how to keep our eyes on the Lord who allows these times to come, and who promises to use them to accomplish His purposes through us, bringing glory to Himself as well as deeper trust in Him for ourselves.

Along with so many Psalms of lament for our pattern, we also have many hymns written during times of duress over the centuries and written for saints who find themselves in such circumstances. Each fall we have reason to give special attention to this when we observe the International Day of Prayer for the Persecuted Church (IDOP), coming on the first Sunday of November. Ministries like Voice of the Martyrs and Barnabas Aid keep the church reminded of the persecution of Christians that has been taking place from the beginning, through every era of history, and on an increasingly intense scale in our life-time even now in the 21st century.

One hymn that is appropriate for this IDOP observance is “Commit Now All Your Griefs,” written in 1653 by Lutheran church musician Paul Gerhardt (1607-1676), and translated into English from the German original by John Wesley. Since there have been a number of translations, so in some hymnals it may be found with the first line set as “Give to the Winds Your Fears.” This can provide us with a very helpful musical expression of the doctrine of providence for our worship, a resource addressing a theme that is so common in Scripture and in the Christian life, but which is not usually given enough attention in the corporate gathering of most churches.

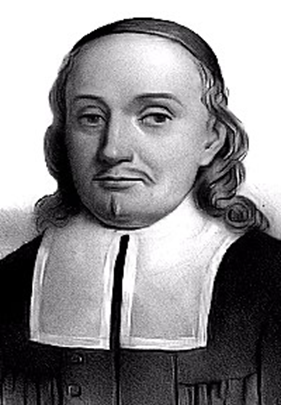

The author of the text to this great hymn was the famous Lutheran Paul Gerhardt, born in Saxony about a century after Luther’s posting of his 95 Theses. He studied theology and hymnody at the University in Wittenberg and then was a tutor in Berlin, where he became friends with another of the great Lutheran musician/theologians Johann Crüger (1598-1662), editor of the most widely used Lutheran hymnal of the 17th century, “Praxis Pietatis Melica” (“The Practice of Piety in Song”). Among the hymns for which Crüger composed music are Johann Franck’s “Jesus, Priceless Treasure” and Martin Rinkart’s “Now Thank We All Our God.” He was among those who served the church during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). He and his family endured many hardships including hunger. He almost died from the plague, and lost five children and his wife in 1936. Crüger married a second time, and this wife was the 17 year-old daughter of an innkeeper with whom he had fourteen children, most of whom died at a young age.

Turning our attention back to the author of the words to the hymn “Commit Now All Your Griefs,” Paul Gerhardt, he served the Lutheran parish of Mittenwalde near Berlin (1651-1657) and then the great St. Nicholas’ Church in Berlin itself (1657-1666). He frequently preached during his time in Berlin. When a doctrinal controversy arose in the region because of an edict from the Calvinist elector, Friederich William, his loyalty to the Lutheran “Formular of Concord” resulted in his being released. Friends helped him settle in Lubben in 1669, where he remained until his death.

He experienced considerable suffering in his life which was for the most part gloomy, along with many of this age who lived through the trauma of loss during the Thirty Years’ War. He himself buried four of his five children, and his wife died after a prolonged illness. He wrote his hymns at a time when German hymnody was changing from a more objective, confessional and corporate character to one that was more pietistic, devotional, and personal. Like many others, his hymns were lengthy and intended for use throughout a service, a group of stanzas at a time. More than 130 of his compositions were published in various editions of Crüger’s “Praxis Pietatis Melica” and other collections. His hymns became widely popular quite rapidly. Others of his 132 hymns in common usage today even outside Lutheran circles include “O Lord, How Shall I Meet You,” “All my Heart This Night Rejoices,” “Why Should Cross and Trial Grieve Me,” and even his translation of the Passion Chorale “O Sacred Head, Now Wounded.”

The Thirty Years’ War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Hymns written during this time reflect the emotional, psychological, physical, and spiritual battles which attacked the hearts of believers seeking to trust God in such horrible circumstances in which they could do virtually nothing except try to survive. It was fought primarily in Central Europe in which an estimated 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle, famine, and disease, including the dreaded bubonic plague. Some areas of Germany experienced population declines of more than 50%. It involved many nations and spread across the borders of many neighboring countries.

It was more than a political and economic power struggle. It has been traditionally viewed as a continuation of the religious conflict that followed in the wake of the sixteenth century Protestant Reformation. When a Roman Catholic dominion became Protestant (usually by the decree of the prince), Roman armies came back to seek to forcibly reverse the change. But after that had been accomplished, Protestant armies were organized to come back to drive out the Roman Catholic influence. As these waves continued back and forth, not only were soldiers and civilians killed in battle. The departing army would often destroy the crops and fields to weaken the returning forces. Disease became rampant from the bodies left in the fields and the starvation of the residents. At the conclusion of the war in 1648, the Peace of Westphalia granted greater freedom for each region to choose and practice the religion they chose. The spiritual struggles of these years is reflected in the hymnody of the period, much of which cries out to God for His providential care.

Gerhardt is ranked, next to Luther, as the most gifted and popular hymnwriter of the Lutheran Church. In 1842 a well-known historian of German literature, Georg Gottfried Gervinus, characterized Gerhardt’s hymnody in these words.

He went back to Luther’s most genuine type of hymn in such manner as no one else had done, only so far modified as the requirements of his time demanded. In Luther’s time the belief in Free Grace and the work of the Atonement, in Redemption and the bursting of the gates of Hell was the inspiration of his joyful confidence; with Gerhardt it is the belief in the Love of God. With Luther the old wrathful God of the Romanists assumed the heavenly aspect of grace and mercy; with Gerhardt the merciful Righteous One is a gentle loving Man. Like the old poets of the people he is sincerely and unconstrainedly pious, naive, and hearty; the blissfulness of his faith makes him benign and amiable; in his way of writing he is as attractive, simple, and pleasing as in his way of thinking.

With a firm grasp of the objective realities of the Christian Faith, and a loyal adherence to the doctrinal standpoint of the Lutheran Church, Gerhardt is yet genuinely human; he takes a fresh, healthful view both of nature and of mankind. In his hymns we see the transition to the modern subjective tone of religious poetry. Sixteen of his hymns begin with, “I.” Yet with Gerhardt it is not so much the individual soul that lays bare its sometimes morbid moods, as it is the representative member of the Church speaking out the thoughts and feelings he shares with his fellow members; while in style Gerhardt is simple and graceful, with a considerable variety of verse form at his command, and often of bell-like purity in tone.

This hymn originally contained twelve stanzas. Many different translators have reduced them to these four which come from John Wesley in 1737. Wesley’s conversion experience energized his soul to seek the heart of Christ and the experiential dimensions of the Christian life and not just the doctrines of the faith. It is not surprising that he was attracted to hymns like this that came out of the deep devotion of pietistic Lutheranism. Wesley’s translations approached the hymn text loosely, especially in structure. His hymns are closely linked to Scripture, and that is reflected in his translation of Gerhardt’s hymn. Faithful to the doctrine of biblical providence, neither writer suggests that all our problems will disappear in this life. But they correctly point us to the Lord who will sustain us through this life until the day when all tears will be dried up at Jesus’ return or our being called out of this world to glory.

As you read (and sing) through the text, you can almost imagine Gerhardt writing this as a personal letter to you, having heard that you are experiencing a difficult time of suffering. Imagine that he has written this hymn just for you, and has sent it to you as his way of offering pastoral counsel that you can go back and read (and sing), in order to redirect the attitude of your heart by remembering the wisdom and goodness of your sovereign God, whose ways may be mysterious at this moment, but whose love should never be doubted.

In stanza 1, Gerhardt counsels you to turn your focus, your attention, away from the waves of the storm, and instead toward the Savior who walks on those waves. The word “commit” should be understood in the sense of “entrust,” transferring your cares to the Lord Jesus. Gerhardt’s words remind us how capable Jesus is to carry our burdens, since He is the one whom earth and heaven obey, the one who directs clouds and winds and seas to accomplish His purposes. He can do for us exactly what we need in every circumstance.

Commit now all your griefs and ways into His hands;

To His sure truth and tender care, who earth and heav’n commands.

Who points the clouds their course, whom winds and seas obey,

He shall direct your wand’ring feet, He shall prepare your way.

In stanza 2, Gerhardt continues his counsel, acknowledging that our fears, sighs, and tears are very real, and more than we can bear. But the Lord sees all of this with a powerful and yet compassionate heart. We have the biblical promises that “God shall lift up your head.” That deliverance may not come as swiftly as we might hope, but it will come in His perfect time. Our responsibility is to keep trusting as we “wait for His time,” confident that, because He has promised, “so shall the night soon end in joyous day.”

Give to the winds your fears; and be undismayed;

God hears your sighs and counts your tears, God shall lift up your head.

Through waves and clouds and storms He gently clears your way;

Wait for His time, so shall the night soon end in joyous day.

In stanza 3, Gerhardt recognizes how hard this may be in the midst of the heaviness we are experiencing now, and so he asks, with a sympathetic heart, “Still heavy is your heart? Still sink your spirits down?” He understands that, and so does the Lord, as Psalm 103:14 tells us that “He knows our frame; He remember that we are dust.” But once again, Gerhardt turns us away from these troubles to look instead at who this Lord is. He is the one who is sovereignly in charge as “He everywhere has sway, and all things serve His might.” Not only so, but on the basis of Genesis 50:20 and Romans 8:28, “His every act pure blessing is.” This is how we can find “every care be gone.”

Still heavy is your heart? Still sink your spirits down?

Cast off the weight, let fear depart, and every care be gone.

He everywhere has sway, and all things serve His might;

His every act pure blessing is, His path unsullied light.

In stanza 4, Gerhardt encourages us to look to the future, “far, far above” our current thoughts, waiting for the day when “His counsel shall appear.” In the midst of the dissonance of our sin-filled world and its conflicts, it is almost always impossible for us to understand what God’s purposes are. And so Gerhardt wisely counsels us to “leave to His sovereign will to choose and to command.” In other words, be patient and live by faith, not by sight, remembering what He has so far revealed to us about His character and His promises. How marvelous to know, then, that one day we will, “with wonder filled,” worship Him for His wisdom and the strength of His hand.

Far, far above your thought His counsel shall appear,

When fully He the work has wrought that caused your needless fear.

Leave to His sovereign will to choose and to command;

With wonder filled, you then shall own how wise, how strong His hand.

Wesley’s text changed the original meter, which required hymnal compilers to use different tunes from those traditionally used with the German text and its more literal English renderings. Tune settings over the years have varied considerably. An early version used the tune JERICHO, a march drawn from Handel’s 1727 opera “Riccardi Primo.” The Wesley were great admirers of Handel’s work, and used this tune in their tunebooks, renaming it HANDEL’S MARCH, which they also used for Charles Wesley’s hymn “Soldiers of Christ, Arise.” In their 1785 collection, “A Pocket Hymn Book,” John recommended OULNEY, a variant of the German hymn tune VON GOTT WILL ICH NICHT LASSEN, dating to 1563, based on a widely popular folk song. The Wesleys changed the tune name to RESIGNATION.

One of the most common and enduring tune settings for John Wesley’s text was produced by Charles Wesley’s son Samuel Wesley (1766–1837), bearing the name DONCASTER. Yet another tune, ICH HALTE TREULICH STILL, comes from a 1736 Leipzig collection, and may even have been written there by Johann Sebastian Bach (though that is by no means certain). It is quite common today to find one of the translations including the one beginning “Give to the Winds Your Fears”) set to George Elvey’s well-known 1868 tune, DIADEMATA, to which everyone sings “Crown Him with Many Crowns.”

Here is a link to the singing of the text to another tune that is frequently used in hymnals, FESTAL SONG, which is found with the text “Rise Up, O Men of God.”