The Protestant Reformation has been recognized, even by secular historians, as one of the most influential events in “modern” history in the west. When Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany on October 31, 1517, he lit a fuse that soon led to a glorious “explosion” of gospel truth that spread fruits of freedom widely throughout western civilization (please pardon the mixed metaphors here!). Few took note of it on that evening of All Saints’ Day, but within a few weeks, local printers had made copies of it, which were quickly and widely distributed so that these matters spread all across Germany.

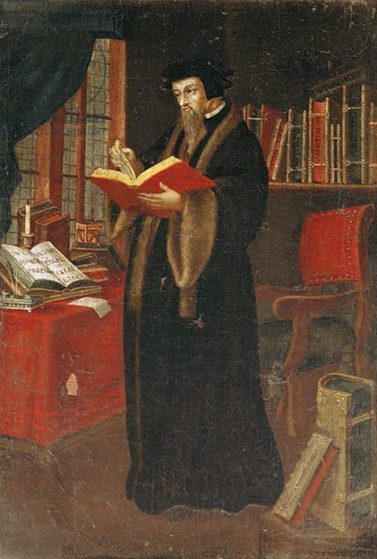

The lasting impact was much broader than the theological issues Luther addressed. Under the second-generation Reformation influence of John Calvin (1509-1564) in Geneva, Reformation principles led directly to such things as quality university education (beyond literacy to liberal arts, beginning with the Geneva Academy), modern democracy (government by elected representatives), care for the needy (through diaconal mercy ministry to widows, orphans, the elderly, and inform), as well as evangelistic missions (with many young men trained and sent out from Geneva into France – most of whom were martyred – and across the Atlantic to Brazil).

But it is with theological and ecclesiastical matters that we are most concerned in this article. At the bare minimum, we would recognize the re-implementation of biblical polity (church government) through governance by the congregational election of men to the offices of pastor/teacher, ruling elder, and deacon, and the priesthood of all believers, with immediate access to God (without a special class of ordained human priests) through the Bible in the language of the people. Following in the same direction as Luther had done a generation earlier, Calvin (who became known as “the theologian of the Reformation”) expanded and deepened the church’s understanding of the rich doctrines of grace, including what are today identified as “the five solas” (sola = alone) of the Reformation (though this formulation is of much more recent articulation): Sola Scriptura, Sola Fide, Sola Gratia, Solus Christus, and Soli Deo Gloria.

For many people in sixteenth century Geneva, their first awareness that things were changing came in unmistakable differences in the morning corporate worship on the Lord’s Day. Some of it was visible, as worship was led from a pulpit rather than at an altar, and all in the language of the people, rather than in the Latin that few lay people could understand. The liturgy was greatly simplified, focusing on prayer, scripture, and preaching. The expository preaching was teaching from the Bible, rather than moral lessons from the lives of the saints. And the style was what became known as lectio continua (“continuous reading”) as the minister preached through books of the Bible week by week, going verse by verse and chapter by chapter. One famous example of that is the account (if true) that after having been expelled from Geneva in 1536 and then begged to return two years later, on his first Sunday back in the pulpit, he opened the Bible to the passage where he had last preached, introducing the next verses with the words, “Now, as I was saying, !”

As the Reformation took hold in Europe, first in Germany and then elsewhere, no less noticeable by the people in the congregation, and perhaps just as stunning in the “newness” of it, was the experience of worshippers (not just the clergy) actually using their own voices to sing in the service. Luther had returned this practice to the churches in German with hymns, some of which he himself had written, like “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” He is general regarded as having composed 38 hymns, some including both words and music. At the Council of Laodicea in 364 AD, the Roman Catholic Church had banned congregational singing in worship. This was, in part, an overreaction against the spreading of heresy by the Arians (who denied the eternal deity of Jesus) through their increasingly popular songs.

In Geneva, Calvin and the church leaders took a different route to congregational singing than Luther had done. In this Reformed branch of the Reformation in Geneva (and in most Reformed and Anglican churches until the 18th century, beginning especially with Isaac Watts, “the Father of English Hymnody”), congregational song in worship was almost exclusively the singing of the 150 Psalms. Over the centuries, many different Psalters have been copied and printed. In fact, the very first book printed in America was the Bay Psalm Book of 1640. It is often noted, not only for its historicity, but also for the grammatical quaintness (some would even say, awkwardness) of its metrical setting of Psalm 23.

The Lord to me a shepherd is,

Want therefore I shall not,

He in the folds of tender grass

Doth cause me down to lie.To waters calm me gently leads

Restore my soul doth He

He doth in paths of righteousness

For His name’s sake lead me.Yea though in valley of death’s shade;

I walk, none ill I’ll fear,

Because Thou art with me, Thy rod,

and staff my comfort are.For me a table Thou hast spread

In presence of my foes;

Thou dost anoint my head with oil

My cup it over-flows.Goodness and mercy surely shall

All my days follow me;

And in the Lord’s house I shall dwell

So long as days shall be.

Calvin’s lasting influence has been perpetuated, in part, through his published works, from correspondence to printed sermons and commentaries on almost every book of the Bible. What an amazing legacy from a man who struggled with terrible health (including frequent bouts with debilitating pain from kidney stones), and died at the relatively young age of 54. But among his many particulars of this incredibly valuable legacy was the Genevan Psalter that he oversaw. Desiring that the people in Geneva learn to sing God’s word, Calvin sought out the finest musicians and poets that he could find to compose the work. That particular Psalter is still in use today around the world, in the original French language as well as in translations to other tongues, including versions in English.

The Genevan Psalter is a collection of 126 melodies, designed to be sung with metrical translations of the 150 Biblical Psalms and three other Scriptural songs. It is sometimes referred to as the French Psalter, as the tunes were designed to be sung with French metrical versions of the Psalter.

As the first and most influential music to be composed specifically by and for Reformed Christians, these tunes represent a significant element of the heritage of all Reformed or Calvinistic Christians.

The melodies were all composed between 1539 and 1562 in Geneva, at the request of Calvin, for use with French metrical translations. No melodies have been added or removed since that time. Many have appeared in several forms, often rhythmically altered. They have been harmonized many times, in many ways, and have been often used without harmony.

While there are still a few denominational groups whose practice is exclusive psalmody, the singing of Psalms is becoming much more common today, especially among Reformed and Presbyterian denominations. In some instances, this is because of newly compiled and published Psalters, and in other instances by the inclusion of more and more Psalm settings in hymnals, along with “hymns of human composition.” What a wonderful development this is, as more and more Christians become conversant with the language and themes of the Psalms. Calvin is famously remembered as the one who said the Psalms are “the anatomy of the human soul,” as they not only show us the character of God, but also that of our own souls, with the whole gamut of our spiritual needs, from penitence to praise, from imprecation to intercession, from lament to liturgy.

There were four individuals whose contributions to the Genevan Psalter were especially noteworthy: theologian and successor to Calvin, Theodore de Beza (1519-1605), poet Clement Marot (1496-1544), and musicians Claude Goudimel (1514-1572) and Louis Bourgeois (1510-1561), the last three being several of the most talented whom he could recruit from France. It was Calvin’s intent to enlist the finest artisans for words and music to craft the Psalter that would be used to teach people about God and about the biblical theology of the Reformation from the Psalms. The fact that this Psalter has continued in worldwide use for nearly five hundred years is powerful testimony to the success of his efforts.

Theodore de Beza, born in Burgundy France, studied law at Orleans. A serious illness from the plague led to his conversion and embracing the Reformed faith. That necessitated his departing his native country and settling in Geneva to work with Calvin, who enlisted him to help with additional Psalm settings for the Psalter. Visiting with Pierre Viret (1511-1571) in Lausanne led to his appointment to teach at the Academy there until 1554. In 1558 he settled back in Geneva where he preached regularly and taught in the Geneva Academy. After Calvin’s death in 1564, Beza led the church very successfully in a period of peaceful spiritual stability.

Clement Marot studied law at the University of Paris, was trained in poetry by his father, and then employed by the French royal court. On several occasions, he found himself in trouble with the law over some of his writings and associations, apparently including sympathies with “heretical” Reformation teachings. By 1534, he had had to flee France, but was able to return a few years later, where he lived while composing his Psalm translations. Eventually he had to leave for good, and went to Geneva in 1543 where he continued working on his Psalms, until dying in Turin the next year. Those Psalm settings are certainly his most significant lasting legacy, as they were welcomed widely among Protestants who were following the lead of Calvin.

As for Louis Bourgois, in both his early and later years he wrote French songs to entertain the rich, but in the history of church music he is known especially for his contribution to the Genevan Psalter. Apparently moving to Geneva in 1541, the same year John Calvin returned to Geneva from Strasbourg, Bourgeois served as cantor and master of the choristers at both the churches of St. Pierre and St. Gervais, which is to say he was music director there under the pastoral leadership of Calvin. Bourgeois used the choristers to teach the new psalm tunes to the congregations. In the 1551 edition of the Psalter, he supplied thirty four original tunes and thirty-six revisions of older tunes. This edition was republished repeatedly, and later Bourgeois’s tunes were incorporated into the complete Genevan Psalter (1562). He left Geneva in 1552 and lived in Lyons and Paris for the remainder of his life.

By 1551, Claude Goudimel was composing harmonizations for some Genevan psalm tunes, initially for use by both Roman Catholics and Protestants. He became a Calvinist in 1557 while living in the Huguenot community in Metz. When the complete Genevan Psalter with its unison melodies was published in 1562, Goudimel began to compose various polyphonic settings of all the Genevan tunes. He actually composed three complete harmonizations of the Genevan Psalter, usually with the tune in the tenor part: simple hymn-style settings (1564), slightly more complicated harmonizations (1565), and quite elaborate, motet-like settings (1565-1566). The various Goudimel settings became popular throughout Calvinist Europe, both for domestic singing and later for use as organ harmonizations in church. Goudimel was one of the victims of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Huguenots on August 17, 2024 , which decimated the Protestant leadership throughout France. Many of the Genevan Psalm tunes we sing in our hymnals are from his hand.

Other than Psalms 23 and 100, Psalm 118 is one of the most frequently found psalm in hymnals, apart, of course, from Psalters. A common setting of it is found in both the 1990 “Trinity Hymnal” (no. 613), in which the Bible’s verses 1-9 and 17-25 are covered in four stanzas, and the 2018 “Trinity Psalter” (no. 118A), which includes the entire Psalm’s 29 verses in eight stanzas. For our study here, we use the setting in the “Trinity Hymnal.” A number of verses from the biblical text are well-known, often quoted by themselves. While all of the Old Testament is most accurately to be understood as Messianic, this Psalm stands out as particularly obvious, especially from the references to the resurrection in stanza 3, and to Christ as the cornerstone in stanza 4. And of course, how often have we heard Lord’s Day services introduced with a call to worship from the verse found in the fourth stanza: “This is the day that the Lord has made; let us rejoice in it and be glad!” (in the scripture at Psalm 118:24).

It is exciting today to read Martin Luther’s opinion of Psalm 118.

This is my own beloved psalm. Although the entire Psalter and all of Holy Scripture are dear to me as my only comfort and source of life, I fell in love with this psalm especially. Therefore I call it my own. When emperors and kings, the wise and the learned, and even saints, could not aid me, this psalm proved a friend and helped me out of many troubles …. Would to God that all the world would claim this psalm for its own as I do!

What a great endorsement for reading, studying, and singing this psalm! Everything in it points to Jesus, and the blessings that are there for those who are “in Him.” Every place in the psalm where we read “I,” we should hear Jesus speaking. He is the worshiper who is coming to the temple in a victory celebration; He is the Moses leading Israel in its final exodus, and the David who has defeated one who was far more menacing than Goliath. Jesus is the stone the builders rejected and the door into the righteous presence of the Father. And best of all, Jesus is the one (in verses 17 and 18) who shall not die, even though severely disciplined (for our sins), but shall live forever, recounting the wondrous deeds of the Lord. Here is the Old Testament predicting Jesus’ suffering, death, and resurrection, as well as His ascension and coronation. It’s all here!

In stanza 1, we echo Jesus’ words in calling all of God’s people to join in praise for the goodness of the Lord. We can do the same as we call one another to join in worship for this purpose and with this theme. And should not the goodness of the Lord be at the center of all our praise, whenever we gather, both in private and in corporate worship.

Give thanks unto the Lord, Jehovah,

for He is good, O praise His name!

Let Israel say: “The Lord be praised;,

His mercy ever is the same.”

Let Aaron’s house now praise Jehovah;

the Lord is good, O praise His name.

Let all that fear the Lord extol Him;

His mercy ever is the same.

In stanza 2, we echo Jesus’ words in pouring out His heart as He bears the intense suffering to which the Lord has called Him, as His foes take their stand against Him. But just as the Lord strengthened Him against His adversaries, so will the Lord sustain us when we come under attack. With Him, placing our trust not in man or princes but in God alone we will celebrate His victory.

In a large place the Lord has set me;

in my distress He heard my cry.

I will not fear; the Lord is with me –

What can man do, when God is nigh?

The Lord is chief among my helpers;

and I shall see my foes o’erthrown:

far better than in man or princes,

my trust I place in God alone.

In stanza 3, we echo Jesus’ words in joyful confidence that since death could not hold Him, then neither can it hold us. He was chastened for our sin, and we endure loving chastening from our heavenly Father to advance our sanctification. But in His mercy we will enter those heavenly gates of righteousness, praising the one who has saved us from all our sin.

I shall not die, but live, declaring

the works of God, who tried me sore,

and chastened me, but in His mercy

not unto death has giv’n me o’er.

The gates of righteousness set open,

the gate of God! I’ll enter in

to praise You, Lord, who pray’r have answered,

and have saved me from all my sin.

In stanza 4, we echo Jesus’ words in celebrating, that though the world turns away from Him, despising the headstone as it tries to build its own godless empire, that effort is doomed to fail, since the Father has announced on that most glorious Easter day the marvelous establishment of the kingdom of His Son and we who have been made the elect, the Son’s spotless bride.

The stone – O Lord, it is Your doing –

the stone, the builders did despise,

is made the headstone of the corner,

and it is marv’lous in our eyes.

This is the day, of days most glorious,

the Lord hath made; we’ll joy and sing.

Send now prosperity, we pray, Lord;

and, O our God, salvation bring!

The tune RENDEZ A DIEU was composed by Bourgeois and used in the 1545 “Strasbourg Psalter,” before appearing in the 1551 edition of the “Geneva Psalter,” where it was used with Psalm 118, and later (in 1562) also for Psalm 98. It was later harmonized in its present form by Goudimel in 1564. The music is also found in hymnals today with the newer text by Erik Routley in his 1972 hymn, “New Songs of Celebration Render,” based on Psalm 98. One of the excellencies of the “Geneva Psalter” was the variety of rhythmic patterns used (meters). To modern singers accustomed to 3/4 or 4/4 markings, frequently in Common Meter (CM) or Long Meter (LM), these tunes can be challenging to sing, since there is not a regular pattern of “beats” per measure. Indeed, there not even measures, but simply musical phrases matching the words.

Here is a link to the singing of the hymn’s four stanzas during the distribution of the elements on a communion Sunday.