Among the treasures in our hymnals are the Welsh tunes that connect us with a small, but significant part of our evangelical history. Wales is that region of southwest England that has a very different geography, culture, and history … and perhaps most recognizably, a different language! That’s evident in the names of the towns in Wales, towns like Caerfyrddin, Aberdaugleddau, Llanymddyfri, and Mwynglawdd. It’s also evident in the name of a well-know collection of Welsh songs popular at community festivals: Gymanfa Ganu. As a side note, here’s the name of a Welsh town that you would see as you passed by a train station for commuters. Try pronouncing this: Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch.

We obviously don’t have any Welsh language hymns in our hymnals. We couldn’t pronounce them if we did! We do have a few that have been translated into English. But you will find a considerable number of Welsh tunes in your hymnal, paired with English texts from other sources. Welsh tunes are easily recognizable as such because of the difficulty of pronouncing their names. Tune names like ABERYSTWTH, BLAENWERN, and LLANGLOFFAN. We sing them frequently without realizing it, as we sing “Jesus, What a Friend for Sinners,” “Jesus, Lover of My Soul,” and “O the Deep, Deep Love of Jesus.”

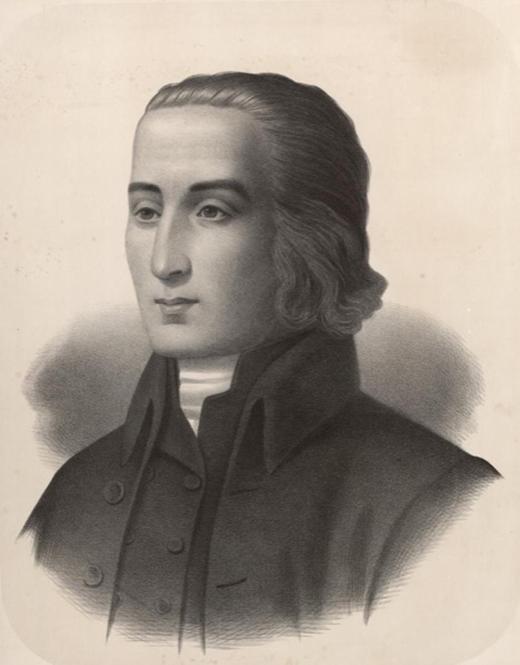

The “Father of Welsh Hymnody” is widely recognized as William Williams (1717-1791), the 18th century Welsh preacher who wrote between 800 and 900 hymns. He was the author of “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah,” translated from Welsh into English by Peter Williams (not related). He was born in Carmarthenshire, Wales, the son of a farmer, and grew up as an Independent. He intended to pursue training as a doctor, attending school at the Dissenting Academy of Llwyn-llwyd, near Talgarth, Wales.

In 1738 while in that area of Talgarth, Williams was deeply affected by the Welsh revivalist preacher Howell Harris. Harris was among those influenced by the Calvinistic Methodist movement, a movement much-influenced in turn by George Whitefield. That sermon created a sense in Williams’ heart that God was calling him to go into the ministry. He started the process toward ordination as an Anglican priest in the church of Wales, but soon discovered that he had the heart of an evangelist. He left his curacy and joined the group of itinerant preachers.

The church in Wales was still singing primarily metrical psalms in their worship. There were no hymns in Welsh at the time, so to promote the creation of Welsh hymns, Harris organized a competition between Welsh preachers. As American hymnologist Louis Benson has written, “the prize fell easily to William Williams, who had the poet’s passion and a gift of verse-writing. Therefore it was not long before he was recognized as poet laureate of the Welsh revival.” Dr. Martyn Lloyd Jones (himself a Welshman!) said, “Certain literary authorities in Wales who are not Christians themselves are ready to grant that he is in their judgement the greatest of all the Welsh poets.” Lloyd-Jones went on to say “that this is something of very real significance, because here you have such an outstanding natural poet now under the influence of the Holy Spirit writing these incomparable hymns.”

In addition to those glowing words, Lloyd-Jones also wrote this about Williams. He called him the best hymn writer there has ever been, an amazing statement! “The hymns of William Williams are packed with theology and experience. You get greatness, bigness and largeness with Isaac Watts, you get the experiential side wonderfully in Charles Wesley; but in William Williams you get both at the same time and that is why I put him in a category entirely on his own – he taught the people theology through his hymns”.

It has been reported that “The Doctor” would often spend time alone for spiritual refreshment by reading the hymns and poems of Williams. While “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah” is the only one to make its way through translation into common use today, in previous generations Welsh hymnals contained many of Williams’ compositions. They contain a contagious spirituality in the warmth of love for Christ which pervades them. Here is an example.

Jesus, Jesus, all sufficient,

beyond telling is Thy worth;

In Thy Name lie greater treasures

than the richest found on earth.

Such abundance,

Is my portion with my God

In Thy gracious face there’s beauty

Far surpassing every thing

Found in all the earth’s great wonders

Mortal eye hath ever seen.

Rose of Sharon

Thou Thyself art heaven’s delight

As an itinerant preacher, Williams’ life resembled the Wesleys. He considered the whole of Wales to be his parish.. For forty-three years he traveled an average of 2230 miles a year. By the end of his ministry, he had traveled more than 150,000 miles, much of that on foot or horseback. There were no railroads at this time, and few stage coaches. Most of Williams’ life was spent, not in a preacher’s study, but on the country roads and through the coal mining towns of Wales in rugged countryside much like the hills of West Virginia. He wrote virtually nothing about himself. It was not until some years later that a biography and analysis of his writings was published. Here is a link to one of the most substantial articles available about him on the internet today.

In 1748 William married Mary Francis who lived in nearby Llansawel. She had previously helped Griffith Jones to set up the Welsh Circulating Schools and was a very capable person who also had musical gifts. She used to sing Williams’ new hymns to tunes she had heard or composed. So it proved to be a very useful partnership. Mary was an only child and upon the death of her parents she inherited a number of properties and land. This, together with land and properties William had inherited from his mother, enabled them to live very comfortably. When some of these properties were sold off, the proceeds were to help with the publishing of his writings and hymn books. With the exception of the short time he was employed as a curate, William didn’t receive any salary or wage. William and Mary were to have 8 children, 2 boys both of whom were to go on to be preachers, and 6 girls, with one dying in infancy. They lived with William’s mother in Pantycelyn, which became the family home and is still today in the hands of one of his relatives.

Williams served as an associate with Daniel Rowlands, another of the Calvinistic Methodist evangelists. From 1776 onwards there is a marked scarcity of any records of Williams’ movements. He continued to preach and lead the society meetings, and he also continued to compose hymns, wrote prose and translated tracts and articles. His health during this time caused him many difficulties. He suffered from kidney stones for those last 15 or so years, and he died on January 11, 1791 at the age of 74. He was buried in the parish church at Llanfair-ar-y-bryn.

His hymn, “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah,” with its allusions to the Israelites being led by the Lord through the wilderness, is a fitting account of Williams’ own life as a pilgrim traveling through “this barren land.” Such a life was not an easy one since it involved much exposure to the raw seasons of nature and the constant fatigue of the traveling preacher. In addition, there was the frequent menace of unfriendly mobs hostile to the message, and the regular danger from robbers on the unpatrolled countryside roads.

This hymn has won its place in almost all American hymnals. “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah” has been used for worship in congregations around the globe and across denominational lines. It was sung by the Welsh Regiments in the trenches in the First World War to keep their spirits up. It is sung with great gusto before the Wales home rugby matches at the Millennium Stadium. It was also incorporated in two of the most televised services of the last two decades, the funeral of Princess Diana of Wales (1997) and the royal wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton (2011). Why would this hymn be used for such significant occasions? Why has this hymn stood the test of time in so many worshiping communities? Williams beautifully interweaves imagery from the Old Testament book of Exodus to evoke a sense of God’s guidance through strife. One of the reasons this hymn has influenced such a broad array of congregants is the universal subject of struggle. Every Christian, and indeed everyone, encounters difficulties. “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah” affirms the reality that God provides for us and ultimately will use all wrong in the world to accomplish His purposes. This God who provided for the Hebrew people wandering amidst “barren lands” with “Bread of Heaven” is still and ever will be a God of providing grace.

The hymn, originally written as six, six-line stanzas in Welsh, was published in 1762 in Williams’ collection of hymns entitled Caniadau y rhai sydd ar y Mor o Wydr (Songs of Those upon the Sea of Glass). In 1771, Peter Williams (1722-1796), no relation to William Williams, translated the first, third, and fifth stanzas into English. The following year William Williams, or his son John, retranslated the third and fourth and added a new English stanza that incorporated Christ. Most modern-day hymnals include just the three stanzas originally translated by Peter Williams. The hymn is most commonly paired with the Welsh tune CWM RHONDDA (1907) composed by John Hughes (1873-1932), requiring repetition of the final line of text in the English translation.

This hymn takes the Exodus from Egypt to the promised land of Israel as a “type” or metaphor of the spiritual pilgrimage of the individual Christian through his earthly life. The words are probably based on Psalm 105, a poetic summary of the Exodus, rather than with the book of Exodus itself. There are also many allusions to the New Testament within the three short verses. It would be difficult to find another hymn that included so much of the Bible, in less than a hundred words.

Stanza 1 refers to the place of our pilgrimage as a barren land: Exodus 15.22. Yet, it also points out that we look to God’s hand to provide: Exodus 32.11. And it reminds us that by His hand He gives us bread from heaven: Exodus 16.4. In John 6:35 we learn that Jesus is that bread!

Guide me, O Thou great Jehovah, Pilgrim through this barren land;

I am weak, but Thou art mighty; Hold me with Thy pow’rful hand;

Bread of heaven, Bread of heaven, Feed me till I want no more.

Stanza 2 refers to the crystal fountain that God opened for them: Exodus 17.6. It also points us to the fiery, cloudy pillar by which God led them: Numbers 9.15-17. And it refers to their deliverance by God: Exodus 18.8. That same God is our Deliverer, our Strength, our Shield.

Open now the crystal fountain, Whence the healing stream doth flow;

Let the fire and cloudy pillar Lead me all my journey through.

Strong Deliverer, strong Deliverer; Be Thou still my Strength and Shield.

The original stanza 3 refers to the mighty power of God who cared for them throughout those 40 years: Deuteronomy 4:37. It goes on to speak of the wondrous works of God as He showed His power in the plagues and Passover: Psalm 106:21-22. And just as God delivered the Israelites from Egyptian bondage, Jesus Christ by His conquest of sin, Satan, and the grave delivers us from this present evil world: Galatians 1.4.

Lord, I trust Thy mighty power, Wondrous are Thy works of old;

Thou deliver’st Thine from thralldom, Who for naught themselves had sold:

Thou didst conquer, Thou didst conquer Sin, and Satan, and the grave.

Stanza 3 ends in climactic fashion with the Hebrew people finally reaching their destination after forty years of wandering in the desert (Joshua 3:9-6:17). It then concludes with the songs of exuberant praise that Israel gave to God for their deliverance: Exodus 15.1ff.

When I tread the verge of Joran, Bid my anxious fears subside;

Death of death, and hell’s Destruction, Land me safe on Canaan’s side;

Songs of praises, songs of praises I will ever give to Thee.

The original final stanza connects the Israelites’ looking forward during their wanderings to the promised land, with our looking forward during our lives on earth to the heavenly home that Jesus has promised: John 14.1-3. With this hope, we eagerly anticipate the time when Jesus shall come and take us to be with Him: 1 Thessalonians. 4.16-17. Thus, in the same way that the Lord gave the people of Israel a rest in Canaan from their bondage and wilderness travels, so there is a rest that yet remains in heaven for the people of God where we can be with Him for all eternity: Hebrews 4.6-10.

Musing on my habitation, Musing on my heavenly home,

Fills my soul with holy longings: Come, my Jesus, quickly come;

Vanity I see, Vanity I see, I long to be with Thee.

And so, these events that happened to Israel are used as a type of our pilgrimage through this life on earth. Just as God led Israel from bondage through the wilderness to the promised land, so we can look to Him to lead us from sin through this life to our eternal home in heaven. This is truly a song of faith in God’s leadership as I call upon Him to “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah.”

Here is a rendition of the hymn as it was sung by a congregation in a church in Wales, with the final phrase actually sung in Welsh.