The beating heart of biblical Christianity is the atonement: why Jesus died and what that death accomplished. In an age when we hear some calling for “deeds, not creeds,” we need a fresh understanding of and appreciation for the doctrine of the atonement. “Progressive” Christianity is the new version of the “Modernism” of a century ago. J. Gresham Machen wrote the definitive critique of this in his 1923 classic, “Christianity and Liberalism.” A new book by Alisa Childers, “Another Gospel?” is now sounding the same alarm for our generation. If our focus is only on “deeds,” doing good things to help solve the world’s societal problems, then our message is no different from that of the non-Christian, and the cross of Jesus becomes meaningless and impotent.

We would be left with the “Therapeutic Moralistic Deism” that has captured so much of mainline Protestantism. It is therapeutic in that it aims to make us feel better about ourselves, to provide the therapy that will help us to have a happier, more fulfilled life, one that will help others as well to reach their full potential and rise above the injustice under which they suffer. It is moralistic in that it is focused on becoming a better person, trying to do what is right in our relationships with one another, living in accord with the principles found in the Sermon on the Mount, seeing Jesus as an example for us to follow rather than the God before whom we bow in worship, having a faith “like” Jesus rather than faith “in” Jesus. It is Deism in that it recognizes God’s existence, but treats Him as one who is merely faintly and indistinctly there in the background cheering us on, without any sense of His sovereign activity in our lives. In short, we become our own saviors. It tells us that our problem is not sin, so we don’t need a redeemer. As Michael Horton (Westminster Seminary, California) has written, “Whereas conservative Christians focus on having our best life now, liberal and progressive Christians focus on creating our best society now. In either case the focus is on ourselves rather than Christ.”

But shouldn’t the focus always be on Christ? The biblical gospel does not ignore “deeds,” but views them as the result, not the essence, of biblical Christianity. “Creeds” are the essential foundation to guarantee that we keep the gospel focus on what God has done for us in Christ. And the most important part of our “creed” is that Jesus died as our atoning substitute, experiencing the curse placed on one who is hanged on a tree (Deuteronomy 21:23; Galatians 3:13), enduring the wrath of God in our place (a “vicarious” sacrifice), paying the penalty for our sin so as to satisfy divine justice. Our “creed” then is that we believe in Jesus’ “vicarious penal sacrifice.”

There is no place in the Bible where that is more clearly and powerfully set forth than in the “Suffering Servant” passage in Isaiah 52:13 – 53:12. It is found there in every single verse of this classic statement of the atonement. It points to Jesus as the perfect fulfillment of the entire sacrificial system God set forth in Leviticus, the perfect Lamb of God on whom our sins were laid and who was then slain in our place. As Rhett Dodson has written in his book on Jesus’ resurrection, “With a Mighty Triumph,” when we look at Jesus on the cross we should think, “That should have been me!”

If Isaiah’s prophecy is really that central to the doctrine of the atonement, then we should be able to sing of it with unrestrained exuberance. And we can do that with this marvelous hymn written in 1941 by Thomas Chisholm, He Was Wounded for Our Transgressions. It follows very carefully the inspired words of that chapter in Isaiah. In it, Chisholm not only virtually placed much of the biblical text in metrical form. He also incorporated the biblical theology that explains what the text means for us in its fulfillment in Jesus’ atoning death.

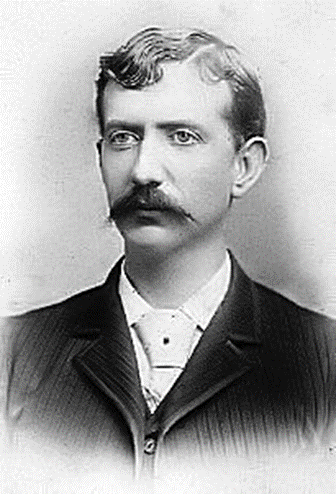

Thomas Chisholm (1866-1960) is best known today for two of his hymns, Great Is Thy Faithfulness, a setting of Lamentations 3:22-23, and Living for Jesus, a song of commitment. He was born in a log cabin in Franklin, Kentucky. Educated in a rural schoolhouse in the area, his family was “dirt poor” and he never got past an elementary school education. However, by the age of sixteen he was a teacher. Five years later, at the age of twenty-one, he was the associate editor of his hometown weekly newspaper, The Franklin Advocate.

In 1893, Henry Clay Morrison, the founder of Asbury College and Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky, held a revival meeting in Franklin. Chisholm attended and responded to the invitation to place his trust in Jesus Christ as his savior. Later, at Morrison’s personal invitation, Chisholm moved to Louisville, Kentucky and became an editor for the Pentecostal Herald. In 1903, he became an ordained Methodist Minister.

Sometime around 1903, he also married Katherine Hambright Vandevere. Due to ill health, Chisholm was only able to serve one year in the ministry. After leaving his ministry in Scottsville, Kentucky he and his wife relocated to Winona Lake, Indiana for the open air. After a time in Indiana, he then moved to Vineland, New Jersey in 1916 where he sold insurance. Retiring in 1953, he moved to the Methodist Home for the Aged in Ocean Grove, New Jersey. He suffered from health issues the rest of his life and had periods of time when he was confined to bed and unable to work. But over the years more than eight hundred of his poems were published, and a number of these were set to music and have found their way into our hymn books. He sent some of the first to Fanny Crosby who wrote back with kind suggestions and words of commendation to encourage him to continue writing.

His hymn, Wounded for Our Transgressions, didn’t actually begin as a hymn, but as a short chorus. He sent it to gospel musician Merrill Dunlop, asking if he could write a tune for it. But Dunlop saw potential in the song to become a full-fledged hymn and asked the author to add some other stanzas. He did so, and Mr. Dunlop provided the tune. And as the saying goes, “the rest is history.” Dunlop was a graduate of Moody Bible Institute and served for a few years after graduating as pianist and organist at Chicago’s Moody Memorial Church. From 1926 to 1953, he served as director of music at the Chicago Gospel Tabernacle. He wrote over 700 hymns and gospel songs before his death in 2002.

The doctrine of Jesus’ substitutionary atonement about which we read in Isaiah 53, and about which we sing in this hymn, has been the consistent teaching of Christianity through the centuries. This is true even from the earliest times in church history. Quoting Michael Horton once again, he has written that “the early Christians were not fed to wild beasts or dipped in wax and set ablaze as lamps in Nero’s gardens because they thought Jesus was a helpful life coach or role model but because they witnessed to Him as the only Lord and Savior of the world.”

In stanza 1, we sing verse 5, that Jesus did all of this for us. It was because He who knew no sin (2 Corinthians 5:21) took our sins on Himself so that our penalty was paid in full. In place of our guilt we have received peace. In place of our bondage He has secured our release. The stripes He suffered from His scourging have resulted in our souls being healed from sin’s curse.

He was wounded for our transgressions, He bore our sins in His body on the tree;

For our guilt He gave us peace, From our bondage gave release,

And with His stripes, and with His stripes, And with His stripes our souls are healed.

In stanza 2, we sing verses 12 (numbered among transgressors, as if He were one) and 4 (esteem Him forsaken by God). This is the part of the historic doctrine of the atonement that liberal (progressive) theology absolutely rejects: that Jesus endured the wrath of God in our place. And yet verse 10 is unambiguous: it was the LORD’s will to crush Him. As He cried out from the cross in the words of Psalm 22, He truly was forsaken by the Father.

He was numbered among transgressors, We did esteem Him forsaken by His God;

As our sacrifice He died, That the law be satisfied,

And all our sin, and all our sin, And all our sin was laid on Him.

In stanza 3, we sing verse 6, probably the most-often quoted sentence in the chapter. It matches what Paul wrote to the Romans, that all have sinned (3:23) and “gone astray.” And it expands on Jesus’ own words in John 10 that He is the Good Shepherd who has laid down His life for His own sheep.

We had wandered, we all had wandered Far from the fold of “the Shepherd of the sheep”;

But He sought us where we were, On the mountains bleak and bare,

And bro’t us home, and bro’t us home, And bro’t us safely home to God.

In stanza 4, we sing verse 8, that looks ahead to the results of this atoning work. The numbers Jesus has delivered from eternal judgment by being judged in their place are a generation beyond numbering. Millions of those who have died “now live again.” We will enjoy an eternity of victorious celebration because of the “victorious Lord” who will come again to take us to be with Him forever.

Who can number His generation? Who shall declare all the triumphs of His Cross?

Millions, dead, now live again, Myriads follow in His train!

Victorious Lord, victorious Lord, Victorious Lord and coming King!

Here you can hear the hymn as an anthem, sing by the choir of Ward Memorial Evangelical Presbyterian Church near Detroit, Michigan.