When a loved one or a dear friend dies, we who know the Lord experience what Paul wrote to the church in 1 Thessalonians 4:13, “We grieve but not like those who have no hope.” As Christians we know that death cannot hold us, but it still hurts terribly. Tears are normal, and even beautiful, at the funeral service of one who has been called home to be with the Lord. But our tears are unique, in that those tears of sadness and mourning are mixed with tears of joy and celebration.

There are few events in which the differences between a Christian and a non-Christian are seen in such stark contrast as at a believer’s funeral. Pastors can testify how often they have seen the difference as they look out from the pulpit over the assembled congregation. There have been those whose faces reflect either the misery of bleak hopelessness or just the struggle to hang on to pleasant memories. And then there are those whose faces glow with that special smile, even through tears, that make it clear that they know “the secret!”

And the secret, of course, is that Jesus has taken away the sting of death, as Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 15:55. All who have placed their faith in Him, trusting in the sufficiency of His atoning, substitutionary sacrifice, can hear Jesus speak to them in their dying moments, just as He did to that thief on the cross, “Today, you will be with Me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43). We can face death, not with misplaced self-confidence, but with total Christ-confidence, knowing that the Savior who died for us has gone to prepare a place for us, that where He is, we may be with Him for eternity (John 14:3).

The theme of preparing “to die well” used to be a familiar one for believers in past generations, including our Puritan ancestors of the 17th century. A recently published book from Puritan and Reformed Publications has called attention to this again in a very compassionate and helpful way.

Elizabeth Turnage has written “The Waiting Room: 60 Meditations for Finding Peace & Hope in a Health Crisis.” She has written with solid theological insights out of the midst of painful experiences in her own life. She has written, “We need to recover the lost art of dying, as Christians.”

We know many, many Bible passages which provide much-needed balm for the soul in the face of death, including the promise in Psalm 23, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for Thou art with me” (KJV), and in Isaiah 43:1-2,” But now thus says the Lord, He who created you, O Jacob, He who formed you, O Israel: ‘Fear not, for I have redeemed you; I have called you by name, you are mine. When you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and through the rivers, they shall not overwhelm you; when you walk through fire you shall not be burned, and the flame shall not consume you’” (ESV). We hear these, and many like it, read at Christian funeral and memorial services.

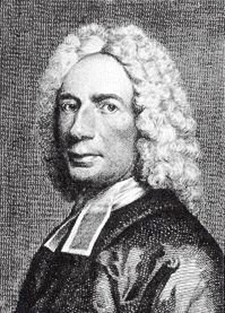

And we also sing many hymns that bring wonderful consolation to grieving hearts in the midst of bereavement. Some of these are rather shallow, sentimental songs that offer little in the way of substance. But there are many which focus not on our feelings as much as on our hope in Christ. One of these is “How Bright These Glorious Spirits Shine,” a powerful hymn that came from the pen of “the Father of English Hymnody,” Isaac Watts (1674-1748), one of over 800 that he composed. Born in Southampton, he was the eldest child of a respected Nonconformist minister who, during Isaac’s infancy, was twice imprisoned for his religious convictions. Young Isaac showed remarkable precocity in childhood, writing impressive poetry at the age of seven. He was taught Greek, Latin, and Hebrew in a Grammar School in Southampton.

The splendid promise of the boy induced a physician of the town and other friends to offer him an education at one of the Universities for eventual ordination in the Church of England, but this he refused. Instead, he entered a Nonconformist Academy at Stoke Newington in 1690, under the care of Mr. Thomas Rowe, the pastor of the Independent congregation at Girdlers’ Hall. Of this congregation he became a member in 1693.

Leaving the Academy at the age of twenty, he spent two years at home, and it was then that the bulk of the “Hymns and Spiritual Songs” (published 1707-1709) were written, and sung from manuscripts in the Southampton Chapel. The hymn “Behold the glories of the Lamb” is said to have been the first that he composed, and was written at the age of twenty as an attempt to raise the standard of praise. It has been claimed that he complained one Lord’s Day to his father that in their worship, that the Psalm texts were poorly written and never enabled them to sing the name of Jesus. His father challenged him to write something better, if he could. And he did!

In answer to requests, other songs followed. The hymn “There is a land of pure delight” is said to have been suggested by the view across Southampton Water. The next six years of Watts’s life were again spent at Stoke Newington, in the post of tutor to the son of an eminent Puritan, Sir John Hartopp. To the intense study of these years should be traced the accumulation of the theological and philosophical materials which he published subsequently. These years were struggles for him because of the life-long frailties of his health.

Watts preached his first sermon when he was twenty-four years old. In the next three years he preached frequently. In 1702 he was ordained pastor of the eminent Independent congregation in Mark Lane, over which the famous John Owen had presided. In this year he moved to the house of a benefactor. His health began to fail in the following year, and Samuel Price was appointed as his assistant in the ministry. In 1712 a fever shattered his constitution, and Price was then appointed co-pastor of the congregation which had in the meantime moved to a new chapel in Bury Street.

It was at this period that he became the guest of Sir Thomas Abney, under whose roof, and after his death (1722) and that of Abney’s widow, that he remained for the rest of his suffering life, residing for the longer portion of these thirty-six years principally at the beautiful country seat of Theobalds in Herts, and then for the last thirteen years at Stoke Newington. His degree of D.D. was bestowed on him in 1728, unsolicited, by the University of Edinburgh. His infirmities increased to be a burden on him up to the peaceful close of his sufferings on November 25, 1748. He was buried in the Puritan resting-place at Bunhill Fields, but a monument was erected to him in Westminster Abbey.

His learning and piety, gentleness and largeness of heart have earned him the title of the Melanchthon of his day. His theological as well as philosophical fame was considerable. His “Speculations on the Human Nature of the Logos,” as a contribution to the great controversy on the Holy Trinity, brought on him a charge of Arian opinions. His work on “The Improvement of the Mind,” published in 1741, was eulogized by Johnson. His “Logic” was still a valued textbook at Oxford into the next century. “The World to Come,” published in 1745, was once a favorite devotional work, parts of it being translated into several languages. His “Catechisms, Scripture History” (1732), as well as “The Divine and Moral Songs” (1715), were the most popular text-books for religious education for many years thereafter. He is best remembered for his “Hymns and Spiritual Songs,” which were published between 1707 and 1709, though written earlier. The “Horae Lyricae,” which contains hymns interspersed among the poems, appeared at the same time. Some hymns were also appended at the close of the several collections of “Sermons” preached in London, published between 1721 and 1724.

His “Psalms” were published in 1719. This was perhaps the most significant innovation of Watts’ hymn-writing, as he took the Psalms of David and re-cast them in New Testament language and theology. Thus Psalm 72, a coronation Psalm for King Solomon, became “Jesus Shall Reign,” and Psalm 98, celebrating God’s coming to judge His world, became “Joy to the World.” And of course, there are in addition to these his well-known hymns, such as “Our God, Our Help in Ages Past,” “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross,” and “Alas, and Did My Savior Bleed.” Some of his hymns were written to be sung after his sermons, giving expression to the meaning of the text upon which he had preached.

As for this particular hymn, here is a moving story reported by John Telford in his 1924 book, “The Methodist Hymnbook Illustrated.”

When Duncan Matheson, the Scotch evangelist, was working in the Crimea, he was returning one night, worn out, from Sebastopol to the old stable at Balaclava where he lodged. He was trudging through mud knee-deep, and the siege seemed no nearer to an end, yet above the stars were looking down from the clear sky. He began to sing, “How bright those glorious spirits shine.”

Next day he found a soldier shivering under a verandah, with his bare toes showing through his worn-out boots. Matheson gave him half a sovereign to buy a new pair. The soldier thanked him.

I am not what I was yesterday. Last night as I was thinking of our miserable condition, I grew tired of life, and said to myself, I can bear this no longer, and may as well put an end to it.

So I took my musket and went down yonder in a desperate state, about eleven o’clock; but as I got round the point, I heard some person singing, “How bright those glorious spirits shine;” and I remembered the old school and the Sabbath school where we used to sing it.

I felt ashamed of being so cowardly, and said, Here is some one as badly off as myself, and yet he is not giving in.

I felt, too, he had something to make him happy which I had not, but I began to hope I, too, might get the same happiness. I returned to my tent, and to-day I am resolved to “seek the one thing.”

Do you know who the singer was? I asked the missionary. No, was the reply. Well, said Mr. Matheson, it was I.

Tears rushed into the soldier’s eyes, and handing back the half-sovereign, he said, Never, sir, can I take it from you after what you have been the means of doing for me.

May the Lord give comfort to us through these words when we gather together to commemorate the memory of departed loved ones, and to celebrate the joy that is theirs now in the presence of the Lord.

The opening phrase of the hymn should be an especially touching thought for the Christian whose spouse, or parent, or child, or close friend has recently died. Rather than seeking consolation only in pictures (or videos) of that one that was dear to us in the past, Watts’s hymn suggests that we instead think of what their appearance must be right now. Our most recent memory may have been the last moments beside a hospital bed, or beside an open casket in the funeral home, or some other sad moment that only increases our grief. Instead, the hymn suggests that we consider “how bright these glorious spirits shine!” Our final contact with this dear one may bring to mind a body that had endured much suffering and had declined to a point of overwhelming physical weakness. But where is that soul now, and what dazzling brightness surrounds that special one, now clad in the white array of perfect holiness? How will they appear to us when we next see them, wearing those white robes, washed in the blood of Christ to spotless purity?

Stanza 1 begins with a magnificent scene, as we imagine the assembled, brightly shining throng before the throne of the Lamb. We ask two questions. The first is, how these “glorious spirits” got “their white array?” and second “How came they” to that position of bliss? Then the second half of the stanza answers both questions. First, these are those who have been raised from this mortal, earthly life of suffering to enjoy now and forever heaven’s “realms of light.” Second, they have been raised to that place of glory because their sinful robes have been washed “in the blood of Christ.”

How bright these glorious spirits shine! Whence all their white array?

How came they to the blissful seats Of everlasting day?

Lo! these are they from sufferings great Who came to realms of light!

And in the blood of Christ have washed Those robes which shine so bright.

Stanza 2 moves on to exult in the condition they now enjoy. There were “triumphal palms” on Palm Sunday as Jesus entered Jerusalem. But that exuberance before Jesus’ exalted position will continue in the life to come, as they (and we) “stand before the throne on high.” It is beyond our ability to fully appreciate here below what enthusiastic praise is being lifted up to this God we love. There in that heavenly realm, “His presence fills each heart with joy.” Our eternal vocation will be singing “glad hosannas” by day and by night. And how encouraging to think that, for those who don’t have the ability to sing in tune now, that His presence will then tune every mouth!

Now, with triumphal palms, they stand Before the throne on high,

And serve the God they love, amidst The glories of the sky.

His presence fills each heart with joy, Tunes ev’ry mouth to sing:

By day, by night, the sacred courts With glad hosannas ring.

Stanza 3 draws from passages in the book of Revelation John’s descriptions of life in glory. What a beautiful catalogue of blessed conditions. No hunger or thirst. No wilting in the sun’s hot rays. Instead of these, God Himself is their cheering Sun, the Lamb is their guiding Shepherd. The Lord feeds them “with nourishment divine,” and He “all their footsteps” will guide. And as in Psalm 23, this Good Shepherd is the Lamb who is our, and their, King, presiding over us all.

Hunger and thirst are felt no more, Nor suns with scorching ray;

God is their Sun, whose cheering beams Diffuse eternal day.

The Lamb which dwells amidst the throne Shall o’er them still preside,

Feed them with nourishment divine, And all their footsteps guide.

Stanza 4 is even more obviously connected with the promises of Psalm 23. The one who has led us, and them, “’mong pastures green” here, will continue there to “lead His flock where living streams appear.” And then the imagery shifts again to the book of Revelation. During our lives here we have each shed many, many tears. But not there, for “God the Lord from ev’ry eye shall wipe off ev’ry tear.” And so we conclude our song with a brief doxology, one that again points us “to the Lamb that once was slain.” That is the only, and the all-sufficient, reason that any of us can be part of that heavenly throng. To Him “be glory evermore!”

‘Mong pastures green He’ll lead His flock Where living streams appear;

And God the Lord from ev’ry eye Shall wipe off ev’ry tear.

To Him who sits upon the throne, The God whom we adore,

And to the Lamb that once was slain, Be glory evermore!

The tune BETHLEHEM (FINK) was composed by Gottfried Wilhelm Fink (1783-1846). Born at Sulza, Thuringia, Germany, he was a German composer, music theorist, poet, and a protestant clergyman. From 1804-1808 he studied at the University of Leipzig, where he joined the Corps Lusatia, and where he made his first attempts at composition and poetry. In 1811 he was appointed Vicar in Leipzig, and served in that capacity for some years. It was there that he also founded an educational institution, leading it until 1829. Around 1800 he worked for the “Allgemeine musikalische Zeitschrift” (General musical magazine). In 1827 he became the magazine’s editor-in-chief for 15 years. From 1838 he was a lecturer at the University of Leipzig. In 1841 he became a Privatdozent of musicology at the university. That year he became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, and a year later was appointed university Music Director.

He was highly esteemed throughout his life as a music theorist and composer, receiving numerous honors and awards, both at home and abroad. The Faculty of Philosophy at Leipzig University awarded him an honorary doctorate. He wrote mostly songs and ballads and collected songs as well. He authored important words on music theory and history, but was best known as editor of the “Musikalischer Hausschatz der Germans,” a collection of about 1000 songs and chants, as well as the “Deutsche Liedertafel” (German song board), a collection of polyphonic songs sung by men. He died in Saxony in the city of Leipzig.

Here is a link to the words and music (from the “Blue” Trinity Hymnal).