Christmas is a time of joy, especially for those who really understand the history and the message about Jesus. And gospel joy is so much richer and higher and deeper than the secular party spirit and gift-oriented celebrations of the culture. Our joy in Christ connects us to a glorious God who has sent His Son to redeem us. The picture of shepherds and angels and a baby in a manger give us what the angels promised: good news of great joy for all the people and a promise-keeping God.

Christmas music adds immensely to our joy at this time of year. It’s hard to imagine a Christmas without “Joy to the World,” “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing,” and “Silent Night.” We have joy that God has kept His promise in Genesis 3:15 and has sent His Son into our world to crush the head of Satan, a victory which we long to see fully occur in its final moment at Christ’s return. We have joy to know that the payment for our crushing debt of sin has been made once for all and that there is therefore no condemnation for us, but only full freedom by His propitiatory sacrifice. We have joy in the security of knowing that He will never leave us or forsake us, and that He will cause all things to work together for our good and His glory.

This is a joy that is real in our hearts, even in the midst of adversity. There is so much sadness in our world today. We know that it will not last forever, but it’s hard to live with it while it continues. We appreciate Sam Gamgee’ s question in “The Lord of the Rings,” “Is everything sad going to come untrue.? Yes, it will. But until then pain and sorrow continue in this fallen world. Even amid the joy of Christmas, disease continues to bring heartache. Even when we drive to family gatherings, ambulances respond to injuries at horrendous traffic accidents. Even when we gather in Christmas Eve candlelight services, darkness and gloom hangs over Ukraine while Russian missiles rain down on them, stealing electricity, water, and heat … and innocent lives.

One of our beloved Christmas songs comes from such tension … joy even amid sadness. “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” was written during America’s Civil War (which was anything but civil, with 620,000 soldiers killed) by a man who suffered deep anguish at the tragic loss of his wife. His son, Charles Appleton Longfellow (1844-1893) was the oldest of six children born to the legendary American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882). Longfellow senior’s original works include “Paul Revere’s Ride”, “The Song of Hiawatha,” and “Evangeline.” He was the first American to completely translate Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy” and was one of the fireside poets from New England. A literary giant, he came to be known as “the children’s poet.”

In 1863, 18 year old Charles left his family’s home on Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a colonial home that had served as General George Washington’s headquarters from 1775-1776. He travelled by train the 400 miles down the eastern seaboard to join President Lincoln’s Union Army to fight in the Civil War. On March 27, 1863, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, assigned to Company “G.” At the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia (April 30–May 6, 1863) he saw no combat duty but spent his time guarding wagons.

Henry’s personal peace was profoundly shaken by what happened to his second wife of 18 years, to whom he was very deeply devoted. Less than two years before Charles’s experiences at Chancellorsville, on July 9, 1861 Charles’s mother Fannie had tragically died after her dress caught on fire. She was standing next to an open window placing locks of her daughter’s hair in a packet, using hot sealing wax to secure it. Her husband, Henry, awakened from a nap, tried to extinguish the flames as best he could, first with a rug and then his own body, but she had already suffered severe burns. She died the next morning, and Henry Longfellow’s own burns were severe enough that he was unable even to attend his own wife’s funeral. He stopped shaving on account of the burns, growing a beard that would become associated with his image. At times he feared that he would be sent to an asylum on account of his grief.

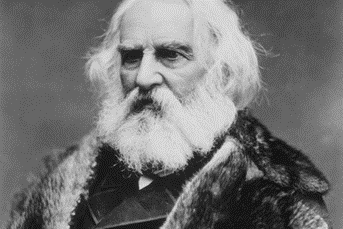

At Chancellorsville, Charley (as he was known) fell ill with “camp fever” (probably typhoid or typho-malarial fever) and was sent home to recover for several months with his family. That summer, having missed the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1 through 3, 1863), he rejoined his unit on August 15, 1863. On the first day of that December, Charlie’s father, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (pictured here) was dining alone at his home when a telegram arrived with the news that his son had been severely wounded, inaccurately stating that he had been shot in the face, four days earlier. On November 27, 1863, while involved in a skirmish during a battle of the Mine Run Campaign, Charley had been shot through the left shoulder, with the bullet exiting under his right shoulder blade. It had traveled across his back and nicked his spine. Charley avoided being paralyzed by less than an inch.

He was carried into New Hope Church (Orange County, Virginia) and then transported to the Rapidan River. Charley’s father and younger brother, Ernest, immediately set out for Washington, D.C., arriving on December 3rd. Charley arrived by train on December 5th. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was alarmed when informed by the army surgeon that his son’s wound “was very serious” and that “paralysis might ensue.” Three surgeons gave a more favorable report that evening, suggesting a recovery that would require him to be “long in healing,” at least six months. On Christmas Day in 1862, the saddened man wrote in his journal, “a merry Christmas say the children, but that is no more for me.”

On Friday, December 25, 1863, Longfellow, as a 57-year-old widowed father of six children, the oldest of which had been nearly paralyzed as his country fought a war against itself, wrote a poem seeking to capture the dynamism and dissonance in his own heart and the world he observed around him that Christmas Day. He heard the Christmas bells ringing in Cambridge and the singing of “peace on earth,” but he observed the world of injustice and violence that seemed to mock the truthfulness of this optimistic outlook. The battle of Gettysburg was no more than six months past. His poem reminds us that we need to look past all those painful reminders of sin, putting our hope in the God who is alive and has promised that one day He will cause everything sad to come untrue.

This is a song for today, not just for the Civil War era. Our world has never known a time without war somewhere, and the Bible tells us that will be true until Jesus returns. We know the history of World Wars, of the genocide in Cambodia, of the slaughter in Rwanda, of the Taliban brutality in Afghanistan, and now of Russia’s terrorist missile attacks against the people of Ukraine. Can we see all that, and still sing of Christmas bells that call for “peace on earth,” as each stanza concludes, echoing the angelic announcement over the skies of Bethlehem? Yes, we can! The Prince of Peace will come again, and once more we can say with Sam Gamgee, “everything sad will come untrue.” O Lord, hasten the day! “Come quickly, Lord Jesus.”

One legitimate criticism of the text is that it suggests a sentimental, self-directed solution. When we’re feeling overwhelmed by the terrible things around us, that all we need to do is adopt a more positive attitude, convincing ourselves that after all, things will all be better in the future. Yes, Longfellow does reference God in the final stanza. And it could be understood to point to what we know is the real answer, that there is a God who is in control and will work all things to accomplish His purposes. That’s certainly how we would want to interpret it. But it’s almost a merely brief tip of the hat Godward. And after all, Longfellow was a Unitarian. He had positive feelings toward Christianity, but his views tended to be more like the nineteenth century Deists who believed in a god who had created the world but was somewhat distant from it now. Unitarians then and now viewed Jesus as more of an example for moral behavior than a divine substitutionary sacrifice. Like late nineteenth and early twentieth century modernists, the goal was not so much to have faith IN Jesus, as to have a faith LIKE Jesus. This lifts Christianity out of the realm of doctrinal history and turns it toward self-help psychology, like so many of the media voices and authors of popular religion of our day. And so for us today, we find our hope not in listening to bells (a subjective approach – focused on feelings), but in listening to the Word of God in scripture (an objective approach – focused on truth). As long as we follow our theology of a sovereign promise-keeping God rather than Longfellow’s, we can legitimately sing the carol.

Here are the original words of Longfellow’s poem. Several stanzas are so closely associated with harsh attitudes about the Civil War that they are not included in hymnals. Asterisks mark the five that are usually found today.

*Stanza 1 takes us to Christmas morning, hearing the bells in the steeple of the nearby church waking us with their carols, and calling us to recall the angels’ message of peace and good news.

I heard the bells on Christmas Day their old, familiar carols play,

and mild and sweet the words repeat of peace on earth, good-will to men!

*Stanza 2 imagines. us pausing to reflect on the fact that around the community, and indeed around the world, the air was filled with the sound of church bells just like ours.

And thought how, as the day had come, the belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along the unbroken song of peace on earth, good-will to men!

*Stanza 3 carries on the thought of those bells continuing to broadcast their message that the most important thing is not what is happening in the world around us, but rather what is within us.

Till ringing, singing on its way, the world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime, a chant sublime of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Stanza 4 belongs to the Civil War era mentality that Longfellow knew, when the thundering of cannons drowned outsounds of the Christmas carols ringing of peace.

Then from each black, accursed mouth the cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound the carols drowned of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Stanza 5 again references the terrible experiences of the Civil War with the imagery of an earthquake leaving a crevice that had split the country in two and plunged households into misery.

It was as if an earthquake rent the hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn the households born of peace on earth, good-will to men!

*Stanza 6 faces the reality of our own feelings, tempting us to give in to despair, as if there is no hope of every achieving that peace, being condemned to live with the ever-present power of hate.

And in despair I bowed my head; “There is no peace on earth,” I said;

“For hate is strong, and mocks the song of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

*Stanza 7 finally brings a positive message in the conclusion. It is the truth on which we have cast our hope: that God is alive and will usher in a day of justice, righteousness, and peace. It is to that which the Christmas bells point us.

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep: “God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail, The Right prevail, with peace on earth, good-will to men.”

It was not until 1872 that the poem is known to have been set to music. The English organist, John Baptiste Calkin (1827-1905), used the poem in a processional accompanied with a melody WALTHAM that he had previously used as early as 1848. He was an organist first in Dublin and then in London before becoming a professor at the Guildhall School of Music. The Calkin version of the carol was long the standard. Less commonly, the poem has also been set to Joseph Mainzer’s 1845 composition MAINZER. Other melodies have been composed more recently, most notably in 1956 by Johnny Marks. Bing Crosby recorded the song on October 3, 1956, using Marks’s melody. It was released as a singleand reached No. 55 in the Music Vendor survey. The record was praised by both Billboard and Variety. It may be that more people today know it from this than from their church hymnals. In 2008, the contemporary Christian music group, “Casting Crowns” scored their eighth No. 1 Christian hit with “I Heard the Bells” from their album “Peace on Earth.”

Here is the song being played on a digital Schulmerich carillon.