Each summer, Protestant denominations in America hold their annual meeting. Depending on the polity (church government) of each, different types of representation from local churches gather to review how their bodies are carrying out the Great Commission. This includes addressing such things as expanding the effectiveness of missions abroad and church planting at home, responding to doctrinal challenges that threaten their biblical integrity, overseeing their educational ministries in colleges and seminaries, overseeing the work of local congregations and regional bodies, and managing printing of educational and training resources.

These assemblies range from delegated meetings of just a few hundred to thousands of delegates coming from every church across the nation, from 150 to 15,000 commissioners. Secondarily, these assemblies are occasions of fellowship as friendships of colleagues are renewed, training in specialized areas of ministry are provided, and perhaps best of all there is corporate worship with great singing, focused prayer, celebrations of the Lord’s Supper, and of course excellent preaching from some of the best pastors in the land.

But among the denominations that will meet, there are significant branches of the church today that have embraced such serious heresies as to be legitimately considered apostate, having become no longer a true church of the Lord Jesus Christ. One of the most blatant examples of this is the way too many have capitulated to cultural pressures in the area of sexuality. Whether it’s abortion, so-called same sex marriage, homosexual clergy and lifestyle, or the absurd woke ideologies of the transgender movement, those of us who love the Lord, the Word, and the gospel, weep to see this widespread abandonment of the truth, something Al Mohler has called theological treason.

With all that in mind, we who seek to remain faithful need to be praying that delegates to these assemblies, and the people back in their local churches who care, will be called back to and kept in fidelity to our foundations. These include what became known as “The Fundamentals” in the modernist controversies of a century, ago chronicled in J. Gresham Machen’s 1923 classic book, “Christianity and Modernism.” Belief in and defense of those fundamentals from that time are just as critical today. They are 1) the inerrancy of Scripture, 2) the virgin birth of Christ, 3) the substitutionary atonement of Christ, 4) the bodily resurrection of Christ, and 5) the reality of the miracles of Christ. These were adopted as such at the 1910 General Assembly of the “Northern” Presbyterian Church, and were articulated in the 4 volume series of articles published in 1917 by the Bible Institute of Los Angeles as “The Fundamentals.”

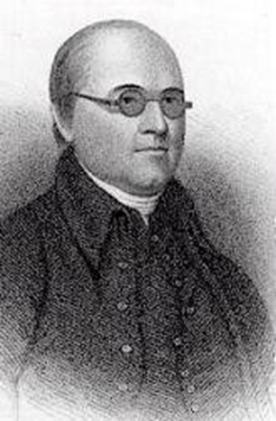

As we sing today, we have a number of fine hymns to help us sing our prayers for God’s blessing on the church. One of those is the 1801 hymn by the then-president of Yale, Timothy Dwight (1752-1817), “I Love Thy Kingdom, Lord.” This is perhaps the earliest hymn composed by an American citizen that is still in current use today. Dwight was a grandson of Jonathan Edwards, his mother having been Edwards’ third daughter. He became a Congregationalist pastor, a Revolutionary War army chaplain, a tutor and professor at Yale College, and then president of Yale from 1795 till his death in 1817. As president he continued to teach and serve as chaplain and was instrumental in improving both the academic and the spiritual life of the college. All of Timothy Dwight’s many accomplishments seem more amazing when it is remembered that for the last forty years of his life, he was unable to read consecutively for more than fifteen minutes a day. His defective eyesight had been caused by a case of small-pox, and the pain in his eyes is said to have been agonizing and constant.

Timothy Dwight is the most important name in early American hymnology, as it is also one of the most illustrious in American literature and education. He was born at Northampton, Massachusetts (where Jonathan Edwards had been pastor), graduated at Yale College, 1769, and then was a tutor there from 1771 to 1777. Following that, he became for a short time a chaplain in the United States Army, but moved on in 1783 to Fairfield, Connecticut, where he held a pastorate, and taught in an Academy until his appointment, in 1795, as President of Yale College. In 1797 the General Association of Connecticut, being dissatisfied with Joel Barlow’s 1785 revision of “Watts,” requested Dwight to do a complete revision of the work. This he did liberally, furnishing in some instances several paraphrases of the same psalm, and adding a selection of hymns, mainly from “Watts.”

Dwight demonstrated a precocious spirit at a very young age, reading the Bible at age 4, learning Latin during grammar school, entering Yale College at age 13, and graduating at the age of just 17. In his valedictory address to the students at Yale in 1776, Dwight wrote: “we have the best foundation to believe that this continent will be the principle seat of that new kingdom.” Dwight believed that the means for establishing this kingdom of God in America included “preaching and hearing the word, reading scripture, prayer, correspondence with religious men, religious meditation, and the religious education of children,” all of which applied to everyone, regardless of church affiliation or participation.

Dwight left a legacy of improved scholastic standards at Yale College, serving not only as the school’s president, but also as professor of literature, oratory and theology, and college chaplain. During Dwight’s tenure at Yale College, Tom Paine’s infamous book “The Age of Reason” was sweeping the country. Yale, like other colleges, had become infected with the “free thought” of Paine, Rousseau, and the French Revolution. It is estimated that there were no more than five who professed to be Christians on the entire Yale campus. Dwight took to the chapel pulpit with his Bible in hand, and his dynamic leadership ignited a spiritual revival in 1802 which soon spread to other New England college campuses as well. A large percentage of students were not only converted during that revival, but many went on to careers in gospel ministry. Thirty men, half of the graduating class that year, became ministers. In the four years following the awakening, 69 graduates went on to pastor churches. A total of 75 out of the enrollment of 225 (one third of the total student body) were converted in that year of the revival.

He may be best known today for his 1797 revision of Isaac Watts’ 1719 “Psalms of David,” to which he added 33 of his own texts. “I Love Thy Kingdom, Lord,” published in the 1801 revision of Watts’ “Psalms of David,” is the only remaining text from that collection which has survived. This was done at the beginning of the Second Great Awakening. Watts had paraphrased only the psalms he deemed fit for public worship. Though psalters from England were still in common usage in America at this time, including Sternhold and Hopkins’ “Old Version” (1564) and Tate and Brady’s “New Version” (1696), Watts’ early 18th century paraphrases were making headway in the American colonies.

Several versions of Watts’ texts appeared in the colonies, including one by Joel Barlow. Barlow’s edition, though widely used, was tainted when he went to France to participate in the French Revolution and reportedly fell into immorality. Dwight was given the task to “disinfect Barlow” by producing a new edition. Dwight’s “Watts” was very successful in Connecticut and used almost exclusively there for over 30 years. Dwight’s version was no longer simply the Christianized rendering of the Hebrew psalter that Watts had originally conceived nearly a century earlier. This new edition had become instead an instrument of evangelism designed to persuade the unregenerate and to comfort the converted.

The original eight stanzas of “I Love Thy Kingdom, Lord” have been reduced to four to six in most hymnals. This paraphrase of a portion of Psalm 137 appeared originally under the title, “Love to the Church.” The author built on a theme from a portion of Psalm 137, the poignant song of the exiled Jews, beginning “How could we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?” (Psalm 137:4), opening up into this Christ-centered hymn that extols the virtues of the church. We recognize theologically that the words “church” and “kingdom” are interchangeable, both referring to the body of Christ, all of us who were chosen from eternity by the Father before the foundation of the world to be the bride for His Son, redeemed at Calvary by the Son as He shed His blood to satisfy divine justice as our substitute, paying for our sin and purchasing us to make us His own, and regenerated by the work of the Holy Spirit as He continues that work of sanctification to make us pure not only by virtue of our justification, claiming Christ’s righteousness as our own, but also becoming more and more like the one who calls us to be holy.

While it is about the church, the kingdom of God, the hymn is addressed to God since it is His church, His kingdom. It reflects an emotional attitude from Dwight’s heart, as He was seeing the Lord begin to work in the hearts of Yale’s students during that revival. For him, and for us, we love (in the deepest and highest sense of the word) that church and kingdom of which we are privileged by sovereign election to be a part, the one and only kingdom that will survive and thrive into eternity, reaching its fullest beauty and majesty when the king of the church, the Lord Jesus, returns in power and glory.

Stanza 1 sings of the kingdom as a house in which the Lord abides with His people. Further, it identifies this church as having been saved “with his own precious blood.”

I love Thy kingdom, Lord, the house of Thine abode,

the church our blest Redeemer saved with His own precious blood.

Stanza 2 sings of the church, secure in her walls, in wonderful imagery “as the apple of Thine eye” (a reference to Psalm 17:8) and as being “graven on Thy hand” (a reference to Isaiah 49:16).

I love Thy church, O God: her walls before Thee stand,

dear as the apple of Thine eye and graven on Thy hand.

Stanza 3 sings of the church as so precious to us that we shed tears for her well-being as we continually offer prayers on her behalf. And we work diligently to advance her work.

For her my tears shall fall, for her my prayers ascend;

to her my cares and toils be giv’n, ’til toils and cares shall end.

Stanza 4 sings of the church as the reason for our “highest joy” as we “prize her heavenly ways” (so much better than earthly ways all around us), enjoying “her sweet communion” as we join others in fulfilling our membership vows and singing “her hymns of love and praise.”

Beyond my highest joy I prize her heav’nly ways,

her sweet communion, solemn vows, her hymns of love and praise.

Stanza 5 sings most directly to Jesus, “our Savior and King,” as the Friend who has brought us into His body, the church, and who assures us of ultimate deliverance “from every snare and foe.”

Jesus, Thou Friend divine, our Savior and our King,

Thy hand from ev’ry snare and foe shall great deliv’rance bring.

Stanza 6 sings of our future hope that is as sure as the truth of God’s own word, that to Zion, His church, the “brightest glories” of earth and the even “brighter bliss of heaven” will be ours.

Sure as Thy truth shall last, to Zion shall be giv’n

the brightest glories earth can yield, and brighter bliss of heav’n.

The tune for this hymn text, ST. THOMAS, first appeared in Aaron Williams’ 1763 collection of tunes. It is also often used with Isaac Watts’ text, “Come, We That Love the Lord.” Williams (1731-1776) was a Welsh singing teacher, music engraver, and clerk at the Presbyterian Scots Church, London Wall. He published various church music collections, some intended for church choirs. Since Williams never claimed authorship of this tune, many believe it was not Williams’ original melody but rather an adaptation from a work by George F. Handel.

Here is a link to several stanzas of the hymn as sung from Houston, Texas.