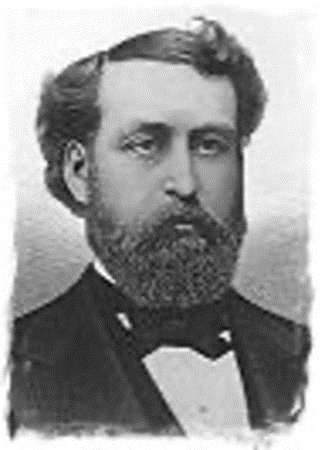

Philip Bliss (1838 – 1876) is one of the greatest names in American hymnody, especially in gospel songs, second only to one of his peers, Fanny Crosby (1820-1915). Every hymnal published in America in the last century will be found to contain numerous hymns by Bliss. These will include both words and music for “I Am So Glad That Our Father in Heaven,” “Man of Sorrows, What a Name,” “The Light of the World Is Jesus,” “Dare to Be a Daniel,” “Let the Lower Lights Be Burning,” and “Wonderful Words of Life.” In addition to those, he wrote words for “With Harps and with Viols” and music for “It Is Well with My Soul,” all these and more written just during the 12 years before his death.

One of his best-known is the focus of this study” I Will Sing of My Redeemer,” probably the last hymn that he wrote before his tragic death. The disaster associated with it also involved the great 19th century evangelist, Dwight L. Moody (1837-1899). Philip Bliss and his wife had arranged to work with Moody in January, 1877, and planned to go to Chicago then. But they got a telegram from Moody asking them to come earlier. They booked passage on the train and left on December 29, 1876, for Chicago. It was a terrible night as a blinding snowstorm whipped over the tracks, leaving huge drifts in its wake. Because of the storm, the train had two engines. As they approached Ashtabula, Ohio, a town on Lake Erie, they had to cross a trestle bridge. The first locomotive made it across, but when the second was on the bridge it collapsed, plunging the engine and the cars behind it down the 75 foot ravine onto the icy river beneath. It was determined later that flood water had weakened the bridge’s supports. A few minutes after the collapse, fire broke out in the cars, fanned by the gale-like winds.

Bliss made it out of the car he was in, extricating himself from under a seat, and climbing through a broken window. He saw that his wife was pinned under her seat. Saying, “If I cannot save her, I will perish with her,” he returned to try to get her out, but as he was doing so the flames took their toll. Not a trace of either of them could be found the next day. It was one of the worst rail disasters in American history. It was reported that 92 of the 160 people on board perished. Investigations later found that the bridge was poorly designed, poorly built, and the icy conditions had weakened it further. Bliss’s trunk filled with the hymns that he was writing did make it to Chicago. One of the texts in it was this one. The well-known gospel song writer, James McGranahan (1840-1907), wrote the tune shortly thereafter. After its publication in 1877, the hymn became a standard in Gospel song collections around the world. McGranahan’s works included “There Shall Be Showers of Blessing.” Interestingly in 1877, “I Will Sing of My Redeemer” became one of the first, if not the very first hymn, to be recorded on Thomas Edison’s new invention, the phonograph. It was recorded by gospel song writer George C. Stebbins (1846-1945), a close associate of Moody and Sankey.

The funeral service was held in Rome, Pennsylvania, where a towering monument was dedicated on July 10, 1877, bearing the inscription, “P.P. Bliss, author … ‘Hold the Fort’.” Memorial services were held throughout the nation for this beloved couple. It was written at the time that no private citizen’s death had ever brought more grief to the nation. Two days after the train wreck that took his and his wife’s lives, on December 31, 1876 a memorial song service for him was held in Chicago. Philip Bliss was only 38 years old. Over 8,000 mourners filled the hall, with 4,000 outside. Moody spoke. His sermon was a call to repentance. How little did the Bliss couple think of their imminent death when they boarded the train to Chicago, he asked. They were ready to die, he knew, but many others were not. What if someone would leave a meeting where he had preached and died on the way home? If he hadn’t preached to prepare people for their deaths, their souls would be on his account, he lamented. This was the gospel testimony that Bliss lived, and the gospel testimony he would have wanted proclaimed in his death.

Philip Paul Bliss was born in a log cabin on July 9, 1838 in the mountain region of Clearfield County, Pennsylvania. He spent most of his childhood years on the frontier of western Pennsylvania. Since the Bliss family moved from place to place in sparsely settled regions, Philip had little opportunity for schooling. He learned the love of singing early in life from his father, who loved to sing aloud. Young Philip would often whistle and sing the same tunes, and occasionally “played” them on homemade instruments. In 1849 at the age of eleven, Philip left home to work on a farm to help ease the burden of the family. After several years of working on the farm, he left to work at a lumber camp as an assistant cook and a lumber jack. During these years, his desire for learning was constantly growing. He used every opportunity he could to increase his knowledge. In 1850, while Bliss was attending school at Elk Run, a Baptist minister conducted a revival among the students. It was during this revival that Bliss made his profession of faith in Christ. A short time later, a minister of the Christian Church baptized Bliss in a creek near his home.

At the age of ten, he heard a piano for the first time, and it deepened his desire to become a musician. At times, he was allowed to go into town to sell vegetables from door to door. This was a means of helping the family budget, but it also put him in contact with others. One Saturday, with his basket of vegetables, the barefooted, gawky, ten-year old boy was to hear the sweetest music that he had ever listened to. The only things that he could play melodies on were reeds plucked from the marshes. Almost unconscious of what he was doing, he climbed the garden fence of a country estate and entered the home unobserved. Standing in the door of the parlor, he listened to a young lady playing the piano, the first he had ever seen. When she stopped, impulsively, he exclaimed, “O lady, please play some more!” Somewhat startled, the woman wheeled and saw the awkward, barefooted boy standing before her and immediately exclaimed, “Get out of here with your big, bare feet!” The boy was unaware that he had trespassed, and he went back to the streets crestfallen.

When Philip was eleven years old, in 1849, he left home to make a living for himself. He was to spend the next five years working in logging and lumber camps and sawmills. Having a strong physique, he was able to do a man’s work. The next several years took him to many places and tutored him in many trades. At the age of twelve, in 1850, he made his first public confession of Christ and joined the Baptist Church of Cherry Flats, Pennsylvania. He does not recall a time when he did not love Christ, but this was remembered as the official time of his conversion. In 1851 he became assistant cook in a lumber camp at $9 per month. Two years later, he was promoted to a log cutter. The following year he became a sawmill worker. Between jobs, he attended school. Uncertain as to what vocation he wanted, he just planned to be prepared for any opportunity that might arise. He spent some of his money in musical education as well. Young Philip remained strong in the Lord amongst the rowdy, laboring men of the camp, although it was not easy, but the spiritual implants of his godly parents were then bearing fruit. He also began to participate in Methodist camp meetings and revival services.

At age seventeen, in 1855, he decided that he would take the final step in preparation for his life’s work. He went to Bradford City, Pennsylvania and finished the last requirements for his teaching credentials. The next year Philip was the new schoolmaster at Hartsville, New York. When school was not in session, he hired out for summer work on a farm. In 1857 he met J. G. Towner (1825-1870), the father of Daniel B. Towner. J. G. Towner conducted a vocal school in Towanda, Pennsylvania. Recognizing that young Bliss had an unusually fine singing voice, he proceeded to give him his first formal voice training. Towner also made it possible for him to go to a musical convention in Rome, Pennsylvania, later that year. Here he met William B. Bradbury (1816-1868), a noted composer of sacred music. By the time the convention was over, Bradbury had talked Philip Bliss into surrendering himself to the service of the Lord. The strong influence of these men in his life helped him to decide to be a music teacher. While still in his teens, Philip discovered that he had ability to compose music. His first composition was sent to George F. Root with this strange request, “If you think this song is worth anything, I would appreciate having a flute in exchange for it.” He received the flute!

Bliss began teaching in 1856 at a school in Bradford County, Pennsylvania. Although he was only 18 and had had little education, the school board saw more importantly “his character and seriousness of purpose.” Two years later, while teaching at an academy in Rome, Pennsylvania, he met the O. F. Young family. He quickly developed a close relationship with the Youngs and was counted as a member of their family. At the Young’s invitation, Bliss moved into their home along with his younger sister. He soon fell in love with their oldest daughter, Lucy. She was a poet from a musical family and greatly encouraged him in developing his musical talents. She was an earnest member of a Presbyterian Church, which he then joined. In later years they were to sing beautiful duets in the service of Christ. Not quite 21, on June 1, 1859, in the home of a local minister, he married Lucy. who was also his sister’s special friend. He had grown to love her deeply and to admire her for her wonderful Christian life. The young groom worked on his father-in-law’s farm for $13 a month while he continued to study music.

He took music pupils in the evening to supplement his income and at 22 had sufficient knowledge of music to become an itinerant music teacher. He went from community to community with a $20 melodeon and an ancient horse. It was the day of the old-fashioned singing school which was frequently conducted by a teacher traveling from place to place. Mr. Bliss delighted in these exercises and his musical ability began to attract the attention of his friends. As a teacher of one of these schools, he recognized his limitations and longed to study under some accomplished musician.

Bliss attended the William Bradbury music convention in Rome in northeastern Pennsylvania. While studying in Rome, Bliss met another of Towner’s students, James McGranahan (1840-1907). McGranahan was two years younger than Bliss and was also born in Pennsylvania. McGranahan had developed an early love for music, but was discouraged by his father saying that he was needed on the farm. Finally, at the age of seventeen, James hired a man to take his place and moved into town so he could work and study music. Bliss and McGranahan remained close friends until the time of Bliss’s death.

Bliss’s wife’s grandmother provided an opportunity for further study in the summer of 1860, by giving him $30 so that he could attend the Normal Academy of Music of New York. This meant six weeks of hard study and inspiration. Upon completion, he took the occupation of professional music teacher in earnest. Within three years, having attended each summer session and studying the rest of the year at home, Mr. Bliss was now recognized as a music authority in his home area, while continuing to travel his circuit. His talent was turning to composition, and his first published number, “Loral Vale,” though not a sacred number, caused him to believe that he could write songs. This number was published in 1865, one year after it was written.

The Blisses moved to Chicago in 1864 when Philip was 26. It was here that he began to conduct musical institutes and became widely known as a teacher and a singer. His poems and compositions flowed out with regularity. He collaborated with George F. Root in the writing and publishing of gospel songs. In the summer of 1865, he went on a two-week concert tour with Mr. Towner. He was paid $100. Amazed that so much money could be made in so short a time, he began to dream dreams. These dreams were short lived. The following week a summons appeared at his door stating that he was drafted for service in the Union Army. Since the war was almost over, the decision was cancelled after two weeks, and he was released. He then went on another concert tour but this one was a failure. However, during the tour he was offered a position with a Chicago Music House, Root and Cady Musical Publishers, at a salary of $150 per month. For the next eight years, between 1865 and 1873, often with his wife by his side, he held musical conventions, singing schools, and sacred concerts under the sponsorship of his employers. He was becoming more popular in concert work, not yet directing his full efforts into evangelical singing. He was, however, writing a number of hymns and Sunday school melodies.

A turning point came in Bliss’s life when he met the great American evangelist, Dwight Moody. One Sunday evening, while Bliss and his wife were out walking, they heard Moody preaching in the open air from the steps of a courthouse in Chicago. After preaching for about thirty minutes, Moody invited the crowd to come inside for the service. That evening, Moody’s normal music director was absent. From the congregation, Bliss’s strong, confident voice caught Moody’s attention. After the service Moody met Bliss and his wife Lucy at the door. Later Bliss wrote, “as I came to him, he had my name and history in about two minutes, and a promise that when I was in Chicago Sunday evenings, I would come and help in the singing at the theater meetings.” This was the beginning of a life- long friendship between Moody and Bliss.

Following their initial meeting in 1869, Moody never ceased urging Bliss to full-time musical service of the Lord. It was Moody’s desire that Bliss and Major Daniel Whittle (1840-1901), a former soldier in the Civil War, should be doing the same thing that he and Sankey were doing, preaching and singing the Gospel as a team. Bliss and Whittle took the challenge very seriously and after much prayer they embarked on a trip together. Bliss wrote in his diary, “Today Whittle and I embark on a new journey in which I pray God will direct my every action and thought.” Together they led a series of meetings in several cities in Illinois. It was during these meetings that both Bliss and Whittle felt God calling them to full time evangelistic work. During a prayer meeting in a pastor’s home, they both dedicated themselves and their talents to the Lord, to be used for His glory. Bliss and Whittle returned home, resigned their jobs, and began traveling together. For a number of years, until the death of Bliss, they held meetings across the country, in a total of twenty-five cities.

During the winter of 1873 Moody again urged him in a letter from Scotland to devote his entire time to evangelistic singing. Bliss was facing a time of decision. At a prayer meeting, Bliss placed himself at the disposal of the Lord, and he decided to lay out a fleece. He would join his friend Major Whittle, a good evangelist, in Waukegan, Illinois, and see what would happen. That was March 24-26, 1874. At one of the services as Bliss sang “Almost Persuaded,” the Holy Spirit seemed to fill the hall, as he later recalled. As he sang, sinners presented themselves for prayer and many souls were won to Jesus Christ that night. The following afternoon, as they met for prayer, Bliss made a formal surrender of his career life to Jesus Christ. He gave up everything, his musical conventions, his writing of secular songs, his business position, and even his work at the church, so that he would be free to devote full time to the singing of sacred music in evangelism, and in particular to be Major Whittle’s song evangelist and children’s worker. At the same time, Whittle dedicated his life to full-time evangelism. A gospel team was born. Little did Bliss know that he only had two and one-half years to live.

Depending upon the Lord to take care of his wife and two children, he joined Whittle in a successful evangelistic career. Bliss compiled a revival song-book for use in their campaigns entitled “Gospel Songs.” It was a tremendous success, bringing royalties of $30,000, all of which he gave to Whittle for the development of their evangelistic efforts. Another source mentions that $60,000 was made and given to charities. Later when Moody and Sankey returned from England, Sankey and Bliss combined their respective books to create the famous,“Gospel Hymns and Sacred Song.” Bliss, of course, was elated at this further exposure of his ministries. Several editions were later published with George C. Stebbins collaborating also. Meanwhile, the Whittle-Bliss team held some twenty-five campaigns in Illinois, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. The 1875 Louisville, Kentucky, meeting was an especially good one. Bliss especially enjoyed working with young people and often conducted his own “praise meetings,” where he would preach and sing.

Their last series of meetings was held in Peoria, Illinois, in 1876. Whittle later said of these meetings, “Had we known that the separation was so near, we would not have planned for ourselves, for the fullest enjoyment of the few days remaining, as our heavenly Father planned for us. In no place were the dear brothers of the ministry more cordial and kind in their welcome and fellowship… I never before witnessed my partner so effective and inspired. His songs were sermons that went deep into the hearts and souls of all those present. I will never forget it! I cannot forget it. It was God’s visitation upon us as His spirit worked among us. It was a real touch of revival and we were sorry the meetings had to end.”

On Friday, November 24, 1876, Bliss sang at a ministers’ meeting conducted by Moody in Chicago’s Farwell Hall. Over 1,000 preachers were present. A favorite song that was sung, was “Are Your Windows Open Toward Jerusalem.” He introduced to the gathering a new song for which he had just written the music: “It is Well with My Soul.” He then had only one month to live. He next conducted a service for the 800 inmates of the Michigan State prison. In genuine repentance, many of them wept as he spoke of the love of God and sang, “Hallelujah, What a Saviour!” The last hymn that he ever sang in a public meeting was one of his own, called “Eternity.”

Bliss spent the Christmas holidays with his mother and sister at Towanda and Rome, Pennsylvania, and made plans to return to Chicago for work with Moody in January. A telegram, however, arrived asking him to return sooner, in order to take part in meetings advertised for the Sunday following Christmas. He wired a message. “Tickets for Chicago, via Buffalo and Lake Shore Railroad. Baggage checked through. Shall be in Chicago Friday night. God bless you all forever.” He decided to leave his two little children, Philip Paul age 1 and George age 4, with his mother. He would not see them again until the family was re-united in heaven.

The overall tone of the hymn is that of exuberant joy, in the knowledge of what Jesus has done for us in our salvation. Like so many gospel songs it is in the first personal singular, as a testimony of one who has been given a new mind, and a new heart, and a new life in Christ. It resounds with the spontaneity of one who cannot stop talking (and singing!) about the saving love of Jesus. The one word which is at the center of this celebration is that of Redeemer. Redemption is one of the biblical words that describes the essence of our salvation. It is a word from the marketplace that in common first century usage referred to the price paid to purchase as slave. In our case that ransom price was the blood of Christ which purchased us to make us on the one hand a slave now owned by Christ, and on the other hand at the same time which has set us free. It is one of the greatest words in the Christian’s vocabulary, one with which we should be very familiar and which should be a part of our worship.

In stanza 1, we sing of the wondrous love of our Redeemer, and that by His suffering and death on the cruel cross, He has set me free from the curse of sin.

I will sing of my Redeemer, And His wondrous love to me;

On the cruel cross, He suffered, From the curse to set me free.

In the refrain, we sing most specifically of the blood that was shed there to pay the penalty for our guilt, knowing that it should have been our blood. The result is a pardon for us that is sealed, and therefore authenticated and guaranteed to be valid for all eternity.

Sing, oh, sing of my Redeemer, With His blood He purchased me,

On the cross He sealed my pardon, Paid the debt, and made me free.

In stanza 2, we sing of Jesus’ boundless love and mercy that has completely changed my present condition (lost) by the enormous cost paid (ransom) to save me from an eternity in hell. As in stanza one, the emphasis is on the fact that this is truly wondrous!

I will tell the wondrous story, How my lost estate to save,

In His boundless love and mercy, He the ransom freely gave.

In stanza 3, we sing of the victory our Redeemer has given. We were faced with a terrifying enemy against whom we had no hope of victory in our strength. But Jesus has achieved that victory for us, a victory over three terrors: sin, death, and hell.

I will praise my dear Redeemer, His triumphant pow’r I’ll tell,

How the victory He giveth Over sin, and death, and hell.

In stanza 4, we sing again of the transition in our current status and in our eternal destiny, having been brought by our Redeemer from death to life, now and forever. Here it is not only wondrous love, but even more exalted: heavenly love.

I will sing of my Redeemer, And His heav’nly love to me;

He from death to life hath brought me, Son of God with Him to be

The tune, MY REDEEMER, was written for these lyrics by Bliss’s friend, James McGranahan in 1877. Born at West Fallowfield, Pennsylvania, the son of a farmer, he farmed during boyhood. Due to his love of music his father let him attend singing school, where he learned to play the bass viol. At age 19 he organized his first singing class and soon became a popular teacher in his area of the state. He became a noted musician and composer of hymns. His father was reluctant to let him pursue this career, but he soon made enough money doing it that he was able to hire a replacement farmhand to help his father while he studied music. His father, a wise man, soon realized how his son was being used by God to win souls through his music. He entered the Normal Music School at Genesco, New York, under William B. Bradbury in 1861-1862. He met Miss Addie Vickery there. They married in 1863, and were very close to each other their whole marriage, but had no children. She was also a musician and hymnwriter in her own right.

For a time he held a postmaster’s job in Rome, Pennsylvania. In 1875 he worked for three years as a teacher and director at Dr. Root’s Normal Music Institute. He became well-known and successful as a result, and his work attracted much attention. He had a fine tenor voice, and was told he should train for the operatic stage. It was a dazzling prospect, but his friend, Philip Bliss, who had given his wondrous voice to the service of song for Christ for more than a decade, urged him to do the same. Preparing to go on a Christmas vacation with his wife, Bliss wrote McGranahan a letter about it, which McGranahan discussed with his friend Major Whittle. Those two met in person for the first time at Ashtubula, Ohio, both trying to retrieve the bodies of the Bliss’s, who had died in that bridge-failed train wreck.

Whittle thought upon meeting McGranahan, that here ass the man Bliss had chosen to replace him in evangelism. The men returned to Chicago together and prayed about the matter. McGranahan gave up his post office job and the world gained a sweet gospel singer/composer as a result. McGranahan and his wife and Major Whittle worked together for 11 years evangelizing in the U.S., Great Britain, and Ireland. They made two visits to the United Kingdom, in 1880 and 1883, the latter associated with Dwight Moody and Ira Sankey’s evangelistic work. McGranahan pioneered use of the male choir in gospel song. While holding meetings in Worcester, MA, he found himself with a choir of only male voices. Resourcefully, he quickly adapted the music to those voices and continued with the meetings. The music was powerful and started what is known as male choir and quartet music. In 1887 McGranahan’s health compelled him to give up active work in evangelism. He then built a beautiful home, Maplehurst, among friends at Kinsman, OH, and settled down to the composition of music, which would become an extension of his evangelistic work. Though his health limited his hours, of productivity, some of his best hymns were written during these days. McGranahan was a most lovable, gentle, modest, unassuming, gentleman, and a refined and cultured Christian. He loved good fellowship, and often treated guests to delightful social feasts. He died of diabetes at Kinsman, Ohio.

Here is a Korean choir singing an anthem arrangement of the hymn along with choir and a lovely soprano soloist.