Luke’s Gospel narrative is unique in many ways, and among them is the attention he gave to the presence and role of angels in his nativity account. It is from the mouth of angels that we have the third of Luke’s nativity hymns, their “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” (glory in the highest to God). This Latin phrase has been featured in many choral settings, like Antonio Vivaldi’s 1715 twelve-movement “Gloria,” often performed by choirs at Christmas time. Luke’s four nativity carols are those of Mary (1:46-55), Zechariah (1:68-79), the angels (2:14), and Simeon (2:29-32). These have each come to be known by the opening Latin words in the 5th century Vulgate: Mary’s “Magnificat,” Zechariah’s “Benedictus,” the angels’ “Gloria,” and Simeon’s “Nunc Dimittis.”

There are quite a few hymns about angels in the Christmas sections of our hymnals. Among them are “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing,” “Angels from the Realms of Glory,” “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night,” “Angels We Have Heard on High,” “The First Noel,” and Martin Luther’s hymn, “From Heaven High (or Above) to Earth I Come,” which puts the whole nativity story into lyrics as spoken by the angel.

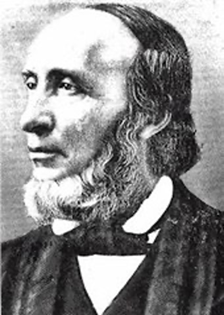

Another of those hymns in which we sing about the angels is “It Came upon the Midnight Clear.” It is the earliest American Christmas carol or hymn that is included in the repertoire of most hymnals and congregations throughout North America. Written on a snowy December Day by Edmund Sears (1810-1876), a Harvard graduate and Unitarian minister, it was first printed in 1849. He wrote this text while serving as a pastor in Wayland, Massachusetts.

Sears is said to have written these words at the request of his friend, William Parsons Lunt, pastor of United First Parish Church, Quincy, Massachusetts for Lunt’s Sunday school. One account says the carol was first performed by parishioners gathered in Sears’ home on Christmas Eve, but to what tune the carol was sung is unknown as Willis’ familiar melody (CAROL) was not written until the following year. Sears’ song is remarkable for its focus not on Bethlehem, but on his own time, and on the contemporary issue of war and peace. It has long been assumed to be Sears’ response to the just ended Mexican-American War.

Born on a farm in Sandisfield, a town in western Massachusetts within sight of the Berkshire Hills, Edmund Hamilton Sears was the youngest of three sons of Joseph and Lucy Smith Sears. As a child, Edmund loved the Berkshire hills near his farm and later told friend and colleague Chandler Robbins that he imagined the hilltops touched heaven and that angel messengers rested on the hilltops between heaven and earth on their errands of love. Edmund’s father Joseph taught him to appreciate poetry and later Edmund wrote that as a child he often did his chores with snatches of poetry running through his head.

Both his father Joseph and mother Lucy taught Edmund the importance of moral principles and encouraged his love of study. Although farm work prevented Edmund from regularly attending school, he advanced in his studies enough to be admitted as a sophomore at Union College in Schenectady, New York in 1831, and he won a prize for his poetry while he studied there. He graduated from Union College in 1834 and studied law for nine months with a lawyer in Sandisfield. After teaching briefly at Brattleboro Vermont Academy, Edmund studied for the ministry under Addison Brown, who was the minister of the Brattleboro Unitarian Church. Edmund became so fascinated with the writings of Boston ministers William Ellery Channing and Henry Ware that he enrolled at the Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, graduating in 1837.

The American Unitarian Association supported his work as a missionary in a frontier area around Toledo, Ohio and in 1838, he served at the First Congregational Church and Society in Wayland, Massachusetts where his congregation was so impressed by his character and preaching that they called him to settle permanently with them. The church ordained and installed him as a minister in February, 1839. While Edmund practiced his student preaching in Barnstable, Massachusetts, he met Ellen Bacon and they were married in 1839. Since he didn’t have ambitions for a large city pulpit, Reverend Sears and his wife settled down for a quiet country life in Wayland.

But as his family gradually grew to four children, Sears discovered that he needed a larger, richer church to support them, and between 1840 and 1847 he served a Congregational Church in Lancaster, Massachusetts. In Lancaster, he suffered illness and depression (perhaps even what would today be considered a nervous breakdown) and his condition grew so severe that he couldn’t project his preaching voice loud enough for a large congregation to hear or endure the physical work required to sustain a large congregation.

Reverend Sears returned to Wayland for a year to rest and recover and when his health improved, the Wayland congregation recalled him and he served there from 1848 to 1865, the year he retired. His lighter workload allowed him more time to write, and from 1859 to 1871 he served as the editor of “The Monthly Religious Magazine.” He contributed articles and poems to several magazines and wrote theology books.

When the Civil War ended, Sears resigned his pastorate in Wayland to write full time, but he accepted a call to succeed Joseph Field at a church in Weston, Massachusetts in 1866. In 1873, Sears enjoyed a European tour. In 1874, he fell from a tree while working in his garden and spent the next two years in constant pain. He died from his injuries on January 16, 1876, and his “Angel Carol” is still sung a century and a half after his death.

It seems strange to us to sing a Christmas carol about Jesus written by a Unitarian, since Unitarians deny the deity of Jesus. But mid-nineteenth century Unitarianism still held on to a strong moralistic appreciation of Jesus, even while failing to embrace the Savior’s redemptive work of atonement. Unitarianism continued to drift into a social gospel of peace and justice, which is evident in the seldom-sung third stanza of Sears’ hymn. In contrast to common Unitarian convictions, Sears wrote that he truly believed in both the humanity and the divinity of Jesus. The hymn’s central theme contrasts the scourge of war with the song of the angels’ peace to God’s people on earth. This is one of the earliest social gospel hymns written in the United States. The movement gathered strength as the 20th century approached, influenced by the writings of Walter Rauschenbusch (1861-1918) and hymns such as Washington Gladden’s “O Master, Let Me Walk with Thee” (1879) and Frank Mason North’s “Where Cross the Crowded Ways of Life” (1903).

It’s unlikely that Sears thought of his song as a carol or that his contemporaries considered it to be such, at least not at first. Traditionally carols were defined as celebrating a seasonal topic and they featured alternating verses and chorus with music suitable for dancing. From the 1150s to the 1350s, carols were popular as dance songs, and gradually their role expanded to processional songs that people sang during festivals. People also used carols to accompany religious mystery plays. Carol singing declined after the Protestant Reformation because Calvinists disliked what they considered “nonessential” and nonbiblical liturgical practices connected with Roman Catholicism.

Contemporary ministers considered Reverend Edmund Sears as what they termed conservative and not sympathetic with broad church or radical Unitarians. Ironically, his theological writings influenced both Unitarian and non-Unitarian liberals. In his writing, Sears expressed both idealism and pessimism about the human condition and explored human nature and the path to salvation. In his 1853 book “Regeneration,” he rejected the doctrine of original sin, but disagreed with some Unitarians about the perfectibility of human nature. Yet, he wrote that people are fashioned in God’s image and can develop their spiritual nature.

In 1834, student Edmund Sears wrote a Christmas carol that he titled “Calm on the Listening Ear of Night,” describing the angel’s anthem resounding across the silent Palestine hills and plains. Many American hymnals printed his first carol, but it was his second carol, “The Angel’s Song” (we know it today as “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear”), that became more popular. In this carol, Sears described an angel chorus singing God’s message of peace on the earth, good will to men. But their songs fall on heedless humanity so immersed in wars and strife that they can’t hear the angel songs or God’s message of peace. Besides these two carols, he wrote between 40 and 50 hymns.

Almost the entire song is centered around the angels who visited the shepherds watching over their flocks by night. There are many details about these events that are correct or likely correct, while others are possible, but are expressions of poetic license added by Sears that do not affect the song’s overall message.

Here are the details that are correct or probably correct:

- Angels visited the shepherds in the middle of the night

- The angel’s message was “peace on earth, good will to men,” through Christ

- The angels had wings, based on other angelic beings who also have wings

Here things that Sears wrote with poetic license:

- The angels were singing (I’ve talked about this several times in previous reviews)

- The angels played with golden harps

- The angels were flying

After the song finishes retelling this glorious event, it tells us that some people have either forgotten or ignored the angel’s message of “peace on earth, goodwill to men” by violating God’s laws and going to war with each other. Still, Christians are warned not to forget this message, as we look forward to the day that we enter eternal life. Until then, we can find rest for our heavy-laden lives, heavily implying Jesus as the source of rest.

Stanza 1 is a description of what is recorded in Luke 2:8-14. Here we find Sears going beyond the words of Scripture to imagine that it was a clear midnight, that the angels were actually singing, and that they had harps of gold. But he did faithfully record their message, though in the language of the King James Version, which is not the most faithful translation of the Greek. More accurately, what they said was, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace among those with whom He is pleased!” But Sears was certainly right in his lyric that “the world in solemn stillness lay,” as most people were almost totally unaware of what a momentous event had taken place in the little town of Bethlehem.

It came upon the midnight clear, that glorious song of old,

From angels bending near the earth, to touch their harps of gold;

“Peace on the earth, good will to men, from heaven’s all gracious King.”

The world in solemn stillness lay, to hear the angels sing.

Stanza 2 continues with direct descriptions of the angels that night. People visiting Bethlehem are very impressed by the grotto memorial beneath the altar floor in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. Even if that were the actual place pf Jesus’ birth, it certainly bears no resemblance in its appearance today to that site when Mary and Joseph brought their child into the world. It is paved with gleaming marble on the floor, and is illuminated by ornate oil lamps of the Orthodox Church. A better place to visit would be one of the fields on the nearby hillside where the angels appeared to the shepherds. There are Bible passages that speak of angels having wings in their revealed appearance to human eyes, so Sears was not outside the bounds of likely accuracy when he wrote of them as bending “on hovering wings.” And he turns preacher when he connects that with today as their message continues to sound “o’er all the weary world” and “its Babel-sounds.”

Still through the cloven skies they come with peaceful wings unfurled,

And still their heavenly music floats o’er all the weary world;

Above its sad and lowly plains, they bend on hovering wing,

And ever o’er its Babel sounds the blessèd angels sing.

Stanza 3 is seldom sung today, since it so closely connects with Sears’ own time of concern over the recent Mexican-American War, and rising tensions that would soon lead to America’s Civil War. Despite the fantastic procession that was the angels’ 2,000 or years ago, Sears reminds singers that the world is a cruel place. It is filled with people who have a depraved mind and do the things listed in Romans 1:28-32, practicing the “deeds of the flesh” that are listed in Galatians 5:19-21, deeds that tragically have often led to war. Sears remembered that too many times in the world people turn a blind eye to “peace on earth, goodwill to men” amid such strife and chaos.

Yet with the woes of sin and strife the world has suffered long;

Beneath the angel strain have rolled two thousand years of wrong;

And man, at war with man, hears not the love song which they bring;

O hush the noise, ye men of strife and hear the angels sing.

Stanza 4 is an appeal to Christians who are experiencing spiritual warfare, struggling to keep on the straight and narrow path, that they should remember that one day, suffering will cease. Life can indeed sometimes bring crushing loads, as we “toil along the climbing way with painful steps and slow.” In the meantime, God provides rest for our weary souls. We should never forget the message of the angels, that there will be peace on earth and goodwill toward those with whom God is pleased.

And ye, beneath life’s crushing load, whose forms are bending low,

Who toil along the climbing way with painful steps and slow,

Look now! for glad and golden hours come swiftly on the wing.

O rest beside the weary road, and hear the angels sing!

Stanza 5 points us to the Bible’s promise, “by prophet bards foretold,” that there will indeed be a wonderful “age of gold.” The peace and joy of that age will not come as a result of human moral improvement. Such was the vain hope of the old liberalism of the late 19th and early 20th century.

No, this will come about at the return of Christ when, with a new heaven and earth, He will be adored by us all, no longer through a glass darkly, but then face to face. That’s when we will see “the whole world send back the song which now the angels sing.”

For lo! the days are hastening on, by prophet bards foretold,

When with the ever-circling years comes round the age of gold;

When peace shall over all the earth its ancient splendors fling,

And the whole world send back the song which now the angels sing.

There are two tunes that are used for the text, one popular in America (CAROL) and the other popular in England (NOEL). The first tune comes from a set of choral studies by New York organist Richard Storrs Willis (1819-1900). Willis was also born in Massachusetts, but after graduating from Yale, he moved to Germany, where he became a student of and close friend and biographer of Felix Mendelssohn. In 1848 he returned to the States and became a journalist, serving as music critic for several newspapers and journals. He also composed a variety of songs and anthems.

The second tune (NOEL) comes from 1874 as English composer Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) set the poem to a different tune that he called NOEL. The carol is widely sung to this tune in England. It was adapted by Sullivan from a folk tune closely associated with the 16 stanza song, “Dives and Lazarus.”

Here is a link to the singing of the text with the CAROL tune found in most American hymnals.