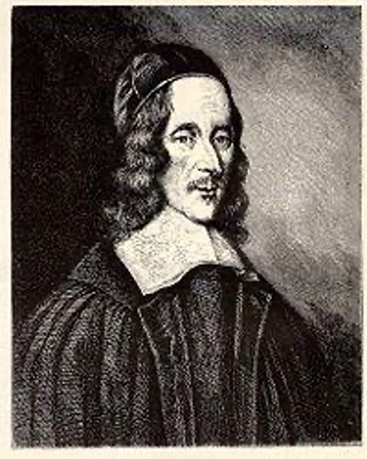

Everyone knows about the work of William Shakespeare (1564-1616). And everyone knows about the King James Bible (1611). And everyone knows about John Milton (1608-1674) and “Paradise Lost.” But not everyone knows about the poetry of George Herbert (1593-1633). All four were contemporaneous in the early seventeenth century, what some would regard as the glory age of the highest peak of the English language. One example of the fine literary production of that period is verses from Herbert which are often sung as the hymn “Let All the World in Every Corner Sing.”

George Herbert was an English poet, orator, and priest of the Church of England, about a century after the Protestant Reformation made its way to England. His poetry is associated with the writings of the metaphysical poets, and he is recognized as “one of the foremost British devotional lyricists.” He was born in Wales into an artistic and wealthy family and largely raised in England. He received a good education that led to his admission to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1609. He went there with the intention of becoming a priest, but he became the University’s Public Orator and attracted the attention of King James I. He sat in England’s Parliament in 1624 and briefly in 1625. King James I (1566-1625), who initiated the translation of the Bible popularly known as the “King James Version,” respected Herbert and considered appointing him an ambassador. The King died before these hopes were fulfilled, so Herbert pursued his original career plans.

After the death of King James, Herbert renewed his interest in ordination. He gave up his secular ambitions in his mid-thirties and was ordained in the Church of England, spending the rest of his life as the rector of the rural parish of Fugglestone St. Peter, just outside Salisbury. He was noted for unfailing care for his parishioners, bringing the sacraments to them when they were ill and providing food and clothing for those in need. He was never a healthy man and died of consumption (tuberculosis) at age 39.

George Herbert was born in Wales, one of 10 children. His family was prosperous and powerful in both national and local government. His father was a member of Parliament and a Justice of the Peace. His mother was a patron and friend of clergyman and poet John Donne and other poets, writers, and artists. As George’s godfather, Donne stood in after his father died when George was three years old. Herbert and his siblings were then raised by his mother, who pressed for a good education for her children.

In 1628 or 1629, Herbert lodged in the north of Wiltshire, the home of his stepfather’s brother and Henry’s elderly widowed mother Elizabeth. A day’s ride to the south lived the family of Henry’s cousin Charles Danvers, who is said to have had a desire for Herbert to marry his daughter Jane. It was arranged for Herbert and Jane to meet, and they found mutual affection; Jane was ten years younger than George. They were married at Edington Church on March 5, 1629. George died soon after in 1633, just three years after beginning his pastoral ministry. Jane survived him, dying in 1661.

All of Herbert’s surviving English poems are on religious themes and are characterized by directness of expression. In“The Windows,” for example, he compares a righteous preacher to glass through which God’s light shines more effectively than in his words. Commenting on his religious poetry later in the 17th century, Richard Baxter said, “Herbert speaks to God like one that really believeth in God, and whose business in the world is most with God. Heart-work and heaven-work make up his books.” It has also been pointed out how Herbert uses puns and wordplay to “convey the relationships between the world of daily reality and the world of transcendent reality that gives it meaning. The kind of word that functions on two or more planes is his device for making his poem an expression of that relationship.”

Herbert came from a musical family. His mother was a friend of the composers William Byrd and John Bull, and encouraged her children’s musical education. George played the lute and viol. Musical pursuits interested him all through his life and his biographer, Izaak Walton, records that he rose to play the lute during his final illness. Walton also gave it as his opinion that he composed “such hymns and anthems as he and the angels now sing in heaven.”

More than ninety of Herbert’s poems have been set for singing over the centuries, some of them multiple times. In his own century, there were settings of “Longing” by Henry Purcell and “And art thou grieved” by John Blow. Some forty were adapted for the Methodist hymnal by the Wesley brothers, among them “Teach me, my God and King,” which found its place in one version or another in 223 hymnals. His poem, “Let all the world in every corner sing,” was published in 103 hymnals, of which one is a French version. Other languages into which his work has been translated for musical settings include Spanish, Catalan and German.

“Let all the world in every corner sing” is from “The Temple,” which was published in 1633, shortly after Herbert’s death. It appeared in the section “Christian Life” under the title “Antiphon (I).” “The Temple” was a very popular work, published in thirteen editions between 1633 and 1679, a total of more 20,000 copies, an amazing publication run in the mid-seventeenth century! It is said that Herbert, on his deathbed at age 39, gave this collection of religious poems to a friend to take to Nicholas Ferrar, a member of the Anglican community at Little Gidding, with the following inscription:

Tell him, he shall find in it a picture of the many spiritual Conflicts that have past betwixt God and my soul, before I could subject mine to the will of Jesus my Master, in whose service I have now found perfect freedom; desire him to read it: and then, if he can think it may turn to the advantage of any dejected poor Soul, let it be made publick: if not, let him burn it: for I and it, are less than the least of God’s mercies.

The title “Antiphon” is a distinct musical form. Think of the related word “antiphonal.” One definition states that it is “a short sentence sung or recited before or after a psalm or canticle.” In this case, however, hymnologist Richard Watson proposes a more literary definition from the “Oxford English Dictionary.” He wrote that it is “a composition in verse or prose, consisting of verses or passages sung alternately by two choirs in worship.” Professor Watson, a scholar of English literature, notes this characteristic of Herbert’s poetry, “… his emphasis on the heart: although the Church sings (or ‘shouts’) psalms, it is the heart which must ‘bear the longest part,’ continue the praise even longer that the Church does.” Pastor J. Christopher Holmes summarized the message of Herbert’s poem:

Herbert’s text is a call to worship. All are constrained to acknowledge God as creator and sovereign. The hymn’s instruction resembles the imperative of Psalm 107:2, that those who are redeemed of God must declare it. Certainly the praise of God’s people will reach Him in the heavens; He is not too distant. As well, as the church proclaims God’s glory, their song will penetrate every barrier, “no door can keep them out.” Herbert’s focus on the human heart is visible in the second stanza, for the heart will continue to praise God throughout eternity.

The prominent theme from the first line is a grand one, one which is repeated at the end in each refrain: “Let all the world in every corner sing,” not just of the greatness of the Lord, but the fact that we are privileged to call Him in such personal and intimate terms, “My God and King!”

In stanza1, we sing of the enormous expanse throughout which God’s praises are to be sung. The spatial dimensions are staggering! All the world – every corner – the high heavens – the low earth. And in all these dimensions His praise must grow, must ever increase in intensity.

Let all the world in every corner sing, “My God and King!”

The heav’ns are not too high, God’s praise may thither fly;

the earth is not too low, God’s praises there may grow.

Let all the world in every corner sing, “My God and King!”

In stanza 2, we sing of the locations of this song of praise that is not only in the psalms that the church shouts corporately, with no door keeping them out, but also within the heart, which Herbert described as the longest part, perhaps meaning the longest in time, stretching into eternity.

Let all the world in every corner sing, “My God and King!”

The church with psalms must shout: no door can keep them out.

But, more than all, the heart must bear the longest part.

Let all the world in every corner sing, “My God and King!”

The famous English composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) helped to bring “Let All the World in Every Corner Sing” back to public awareness when he included it as the final movement of his “Five Mystical Songs” (1911), all of them poems by George Herbert. As a hymn, several different musical settings of the text have been utilized in congregational singing.

The tune most commonly associated with this text is LUCKINGTON, by English organist and composer Basil Harwood (1859-1949), from the “Oxford Hymn Book” (1908). It is said to be named after the village in Wiltshire, England. Harwood’s setting encapsulates the verses between a chorus at the beginning and the end, similar to Herbert’s text. The melody involves some text painting. In stanza one, at “The heav’ns are not too high” and “His praise may thither fly,” the melody rises upward, whereas in “The earth is not too low,” the melody moves downward to its lowest point. The affect of this on the second stanza is not quite the same but is still intriguing. The wide range of the melody makes this tune potentially challenging for average singers and small congregations.

Another common tune setting is AUGUSTINE by the British hymnologist Erik Routley (1917–1982), first published in the 1964 “Hymns for Church and School.” Routley’s commentary on this tune was published posthumously in “Our Lives Be Praise” (1990), as follows:

AUGUSTINE . . . was the direct result of one of my then young children expressing discontent with the tune we all knew for “Let all the world,” so I facetiously remarked that I would try to replace that jubilant piece with one in B-flat minor. What may be more important, however, is that this is the only tune current in Britain that sets the poem as George Herbert wrote it. Brent Smith of Lancing had composed one—and a good one—for the school in this form, but it never travelled beyond the school.

In the United States, some Methodist and Southern Baptist and Presbyterian hymnals have relied on a tune by Robert G. McCutchan, ALL THE WORLD, written for “The Methodist Hymnal,” a 1932 publication. In his 1937 commentary for “Our Hymnody: A Manual of the Methodist Hymnal.” he wrote:

LET ALL THE WORLD was written especially for this hymn. Its meter is peculiar, and other settings did not seem to make the right appeal. Herbert called this poem “Antiphon,” and wished the congregation to sing the first two lines as a chorus with the other four lines as a solo. This setting, being in unison, lends itself admirably to that treatment.

Here is a link to McCutchan’s tune in the Trinity Hymnal.