It can be very hard to live with painful experiences as Christians, wondering “Where was God?” We love Him and trust Him, but still struggle when His providence permits heartbreaking events. He is our Heavenly Father; we are His adopted children; He has told us that He loves us. We have no doubt that He will be with us always, even when we go through the valley of the shadow of death (Psalm 23) or go through the deep waters and fire (Isaiah 43). And we know that He is absolutely sovereign, so there is nothing that happens to us apart from His will. But we can’t help but wonder why He allows things that hurt us so much. We call these matters of “theodicy;” how do we justify God in things He does which don’t make sense to us?

Some of those things that trouble us are personal and private: a cancer diagnosis, the death of a child, a disastrous car accident, the impact of vision loss. Others are just as private and personal, but more emotional than physical: a friend that turns on us, a wonderful job where we’re terminated, a child that turns away from the Lord, an embarrassing realization of our inadvertently having hurt another. Other things bring us distress and confusion from events around us that touch us and steal our peace of mind: a devastating storm, a destructive flood, a terrorist attack, the outbreak of war, the collapse of a government.

All of these things (and more) are the result of sin’s influence in our fallen world. Things are not as they were supposed to be, as described in Cornelius Plantinga’s 1996 book “Not the Way It’s Supposed to Be.” Our Westminster standards describe it well: that we live a life of “sin and misery.” When suffering and tragedy hit home in our lives, even if we don’t turn away from the Lord (as unbelievers will so often do), we can’t help but wonder where He is, and why He has allowed this to happen.

Even in the midst of the terrible, extreme brutality and suffering and death in war, we ask those questions, and find the same answer: that we can trust a sovereign God who not only loves us but is working out His perfect plan. And that includes the realization that His plan is not just for me. It is much bigger, and includes His plan for all things, all events, all people, and all time. As Paul wrote in Ephesians 1:11, our God is the one who “works all things according to the counsel of His will.” How many times in Scripture do we discover times when His design was hidden at the moment, but which made sense later, as when Joseph told the brothers who had sold him into slavery, “What you meant for evil, God meant for good” (Genesis 50:20).

This answer will not be satisfying to unbelievers, but it should be helpful to those of us who know the Lord and believe His Word. It is this, basically. He is perfectly wise and loving and powerful; everything He does is right. But He is infinitely so in all of His attributes, which means that “His ways are as high above our ways as the heavens are above the earth” (Isaiah 55). It should not be a surprise to us that we who are finite cannot fully comprehend the purposes and plans of a God who is infinite! It is vain for us to think we could ever be able to do that.

Covenant theology gives us wonderful help in grasping this important truth, with its focus on the unity of the revelation God has given us. This doctrinal perspective points to the Bible having a single story, a linear theme of God’s glory and grace that was unfolded one step at a time, “from Genesis to the maps!” The Bible is not a collection of morality tales to show us how to be nice to one another and to the planet, as we sometimes hear from pulpits that have missed the message. No, it is a single story of redemption that includes the war between the kingdom of God and His Son and the kingdom of fallen man and the Devil, as announced in Genesis 3:15, “I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; He shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise His heel.” And the book of Revelation assures us of a glorious conclusion, with the succinct message of that book so well summarized in the two words, “Jesus wins!”

And so, as we live in the moment of troubles that distress and confuse us, we return to our confidence that though there will be much that we cannot understand now, we can trust that our heavenly Father knows and does what is best, even when we can’t understand His ways. Job certainly couldn’t! What God wants is not that we try our best to figure out what He’s doing, but that we love and trust Him as He works His mysterious will, knowing that as we read in Isaiah 14:24-27 …

The Lord of hosts has sworn:

“As I have planned,

so shall it be,

and as I have purposed,

so shall it stand,

that I will break the Assyrian in My land,

and on My mountains trample him underfoot;

and his yoke shall depart from them,

and his burden from their shoulder.”This is the purpose that is purposed

concerning the whole earth,

and this is the hand that is stretched out

over all the nations.

For the Lord of hosts has purposed,

and who will annul it?

His hand is stretched out,

and who will turn it back?

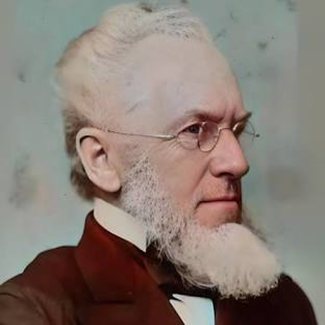

A hymn that very helpfully guides our thinking in these matters of the greatness of God’s will is “Lord, My Weak Thought in Vain Would Climb.” It is not very well known, but ought to be. It provides wonderful insight that can re-shape our thinking in more accurate and constructive ways when we are facing these tough moments in our lives. It was written in 1858 by Ray Palmer (1808-1887). The son of a judge, he was born in Little Compton, Rhode Island. Better known for his 1830 hymn, “My Faith Looks Up to Thee,” written soon after graduating from college during a teaching engagement in New York, he is often considered to be one of America’s best nineteenth-century hymn writers.

After completing grammar school, he worked in a Boston dry goods store, but a significant religious awakening prodded him to study for the ministry. He attended Yale College (supporting himself by teaching) and was ordained in 1835. Later, while in Boston, he joined the famous Park Street Congregational Church. Palmer was a popular preacher and author, writing original poetry as well as translating hymns. He published several volumes of poetry and hymns.

On leaving college he taught for a year in a private school for young ladies in New York City, and then returned to New Haven where, at first in connection with Dr. E. A. Andrews and later as sole proprietor, he conducted the Young Ladies’ Institute, in Wooster Place. In the meantime he was married, October 3, 1832, to Ann Maria, daughter of Marmaduke Waud, a merchant of Albany, of English birth. He also pursued theological studies while in New Haven, and on completing his schooling, in the fall of 1834, moved to Boston, and began to preach. In 1835 he accepted a call to a new church (now called the Central Church) in Bath, Maine, where he was ordained.

Fifteen years of earnest, practical labor followed, after which rest and change of scene were needed, and on December 10, 1850, he was installed as the first pastor of the newly formed First Congregational Church of Albany, New York. Here he continued for fifteen fruitful years of labor, until April 18, 1866, when he was dismissed to accept the secretaryship of the American Congregational Union in New York City. In that position, he served the churches for twelve years, until May 1, 1878, during which time more than 600 churches were aided by this society.

As the salary was insufficient, he was stimulated to a good deal of literary labor during this period. In May, 1870, he moved his residence to Newark, New Jersey, where he spent the rest of his life. On retiring from the service of the Congregational Union, he devoted himself to literary work almost exclusively. In November 1881, he became acting pastor (Dr. Hepworth having the care of the pulpit) of the Belleville Avenue Congregational Church in Newark, and this arrangement continued for three years.

On February 12, 1883, he had an attack of apoplexy, a cerebral hemorrhage, and was partially paralyzed as a result of that stroke. He rallied, however, and showed afterwards considerable vigor of mind and body. His infirmities increased with the years ahead, and on February 6, 1886, he suffered from a second attack, from which he again rallied surprisingly. But on February 20, 1887, a third attack came, and on March 22 a rapid degeneration of the brain began. He died March 29, 1887, at the age of 78. His wife died on March 8, 1886. Of their ten children, one son, also a graduate of Yale, and two daughters survived him.

The theme of this hymn is a tremendously true and helpful one. When we are facing painful and puzzling circumstances, out natural reaction as Christians is to wonder “Why”? That was the case with the disciples when a blind man approached Jesus, and they asked, “Who sinned? This man or his parents?” Jesus’ answer to them is the same answer to us when we ask the “Why?” question: it is that God may be glorified. As finite created beings, we cannot understand the great purposes of our heavenly Father, and we don’t need to know what those are. All we need to know is that He is good and powerful, and that He loves us. That will help us to stop trying to figure out what He’s doing, and simply walk faithfully, trusting Him as He works His sovereign will. That is what we sing in this hymn.

Stanza 1 acknowledges, with humility, that we are incapable of climbing up to grasp those profound truths. It is what we read in Isaiah 55, that as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are God’s ways higher than our ways. To attempt to rise high enough to see what He sees and understand what His immediate purposes are would be in “vain,” a word Palmer uses twice in this first stanza. We are incapable of searching “the starry vault profound,” or finding “creation’s utmost bound,” where God sits enthroned in royal majesty, in the control center of the universe.

Lord, my weak thought in vain would climb

to search the starry vault profound;

in vain would wing her flight sublime

to find creation’s utmost bound.

Stanza 2 goes further to acknowledge that our thoughts are too weak to “search Thy great eternal plan.” This God of ours is the Alpha and the Omega, the one who knows the beginning and the end. He knows all these things not by gazing into some heavenly crystal ball to see the future, but knows all of this because He has determined what He will do from timeless eternity past, “long ages ere the world began.” Our thoughts are too weak to comprehend “Thy sov’reign counsels,” but because they were “born of love,” we can live each day with trusting hearts.

But weaker yet that thought must prove

to search Thy great eternal plan,

Thy sov’reign counsels, born of love

long ages ere the world began.

Stanza 3 could be understood as a confession, not only of our inability, but also of our sinful pride to think that “my dim reason would demand” an answer from God as to what He has ordained. To “demand” such a thing from God is the height of arrogance and presumption. He does not owe any explanation to us, other than what He has already revealed in His Word, that “The secret things belong to the Lord our God, but the things that are revealed belong to us and to our children forever” (Deuteronomy 29:29). We stand at the edge of “some vast deep,” into which we are incapable of peering to see the secrets of His will. Once again, we find the word “vain.”

When my dim reason would demand

why that, or this, Thou dost ordain,

by some vast deep I seem to stand,

whose secrets I must ask in vain.

Stanza 4 moves toward an answer for our troubled minds “when doubts disturb.” This should remind us that Satan will try to use such times to tempt us to doubt God’s presence and promises and purposes. It will be His intent to stir up anxiety and uncertainty in our hearts, creating a sense that “all is dark as night.” But we should be forewarned of his demonic strategy and not be surprised by it. Keeping the eyes of our heart focused on our Savior, we will be able to rest on Him, our solid rock, knowing that whatever “seemeth good to Thee” is enough for us.

When doubts disturb my troubled breast,

and all is dark as night to me,

here, as on solid rock, I rest

that so it seemeth good to Thee.

Stanza 5 is a doxology of sorts, enabling us to not only rest in God’s sovereign will, but also to rejoice in it. More so than in the previous stanzas, in this one we are speaking directly and believingly to the Lord Himself. Knowing “that evermore Thou rulest all things at Thy will; Thy sovereign wisdom I adore, and calmly, sweetly, trust Thee still.” What a glorious conclusion to this hymn. If accompanied on a fine pipe organ, the previous stanzas would be sung with lighter, perhaps even darker, registration. But in this final stanza, it’s time to literally pull out all the stops and sing triumphantly with full voice, even adding the sparkling zimbelstern, if available!

Be this my joy, that evermore

Thou rulest all things at Thy will;

Thy sov’reign wisdom I adore,

and calmly, sweetly, trust Thee still.

The tune CANONBURY is used for this text in the 1990 “Trinity Hymnal.” It is quite a familiar tune to most people, as it is commonly used for Francis Ridley Havergal’s text, “Lord, Speak to Me, That I May Speak.” This tune was derived from the fourth piano piece in Robert Alexander Schumann’s 1839 “Nachtstücke,”Opus 23. CANONBURY first appeared as a hymn tune in J. Ireland Tucker’s 1872 “Hymnal with Tunes, Old and New.” The tune’s title refers to a street and square in Islington, London.

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) began composing music at the age of seven. He wrote no hymn tunes himself, though a few of his lyrical melodies were adapted into hymn tunes by hymnal editors. One of the greatest musicians of the Romantic period, Schumann did not at first seem destined for a musical career. Although he was a precocious piano player, his mother and his guardian insisted that he study for a legal career. From 1828 to 1830 he studied law at Leipzig and Heidelberg Universities, but much of his time was consumed with music and poetry. From 1830 until his death Schumann devoted his life to music. His teacher, Friedrich Wieck, assured him he could become the finest pianist in Europe, but an injury to his right hand (from a practicing method) ended that dream in 1832, causing him to turn completely to composition. Schumann composed successfully in many genres, but became especially famous for his piano works and song cycles.

In 1840, against the wishes of his father, he married Clara Wieck, whom he had known since 1828. She was the daughter of his former teacher and inspired many of Schumann’s songs. They had four children: Marie, Julie, Eugenie, and Felix. Clara also composed music and had a considerable concert career in her own right, the earnings from which had formed a substantial part of her father’s fortune. When he and Clara went to Russia for her performances, he was questioned as to whether he also was a musician! He harbored resentment for her success as a pianist, which exceeded his ability as a pianist and reputation as a composer. In 1834 Schumann founded the magazine “Neue Zeitschrift für Musik” and edited it for ten years.

He suffered from depression for much of his adult life. From 1844 to 1853 he was engaged in setting Goethe’s “Faust” to music, but was again plagued with imaginary voices (angels, ghosts, or demons) and in 1854 jumped off a bridge into the Rhine River, but was rescued by boatmen and taken home. For the last two years of his life, after the attempted suicide, Schumann was confined to a sanitarium in Endenich near Bonn, at his own request, and his wife was not allowed to see him. She finally saw him two days before he died, but he was unable to speak. He was diagnosed with psychotic melancholia, but died of pneumonia without ever recovering from his mental illness.

Some have speculated that the cause of his late term maladies could have been that he suffered from syphilis, contracted early in life, and that he had been treated with mercury, unknown to be a neurological poison at the time. A report on his autopsy revealed that he had a tumor at the base of the brain. It is also surmised that he may have had bipolar disorder, accounting for such extreme mood swings and changes in his productivity. From the time of his death, Clara devoted herself to the performance and interpretation of her husband’s works.

As with a number of fine older texts, “Lord, My Weak Thought in Vain Would Climb” has been set to a newer tune in a contemporary style. When this is done, it is called a “re-tuned” hymn. Here is one such example, composed by Travis Lamb: https://youtu.be/Jkzcnouyam4.

Here is a link to the music of CANONBURY.