One of the most wonderful words in a Christian’s vocabulary is “grace.” It thrills us (and honors the Lord) to remember what God has done for us … and why. He has taken on Himself, through His Son, the punishment for our sins, thereby satisfying divine justice, so that He is both just and the justifier of the ungodly (Romans 3:26). And this has been accomplished apart from anything we have done. We were incapable of doing anything to earn or achieve, or even maintain, this standing of being forgiven sinners and adopted children of God.

From the very earliest pages of Scripture, we find God to be a God of grace. After Adam and Eve sinned by their disobedience in the Garden of Eden, God did not pour out His wrath on them, as they deserved. Instead, He announced a covenant of grace with His Son by which He Himself would rescue their descendants, who had fallen by virtue of the fall of Adam, their federal head, their representative. It was grace that prompted Him to do that. It was grace that led Him to save Noah and his family (“Noah found grace in the eyes of the LORD,” Genesis 6:8). It was grace that prompted God to come to Abraham with His promise to make Him the father of a great elect nation, more numerous than the stars of the heavens or the grains of sand on the seashore, as recorded in Genesis 22:17.

Over and over again through the pages of biblical history, we find God at work taking the initiative to save people who did not deserve such mercy. One of the greatest pictures of this is to be found in the account of the Exodus, which became a common theme in the Psalms of praise as a model of God’s grace to His people. His deliverance was not based on anything of merit in them. He did not give them the Ten Commandments ahead of time, as if to say, “If you will obey My law, then you will have earned the deliverance from bondage that I offer you.” No, He delivered them from Egyptian slavery by grace, and only then gave them His law, not as a means of earning salvation, but as a guide for how to live as people who had been saved by grace. We see that in the opening words of the giving of the Law in Exodus 20, “I am the LORD your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.” Then come the commandments.

Not only is “grace” the dominant theme found throughout the Bible. “Grace” is also one of the most dominant themes in our hymnals. Look at the Table of Contents in the front and in the Topical Index in the back, and you will find many hymns about grace. In addition to hymns that have grace as their theme, these will include those that actually have the word “grace” in the opening line, as in such familiar hymns as “Amazing Grace,” “Wonderful Grace of Jesus,” and “Marvelous Grace of Our Loving Lord.”

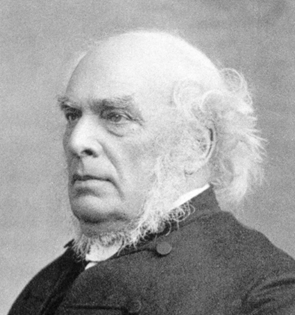

In this study, we are considering one of these with grace as the theme, even if not in the opening line. The rich dimensions of sovereign benevolence are communicated with wonderful poetic beauty in the hymn “Not What My Hands Have Done,” written in 1861 by the great Scottish preacher and lyricist, Horatius Bonar (1808-1889), known by his friends as Horace. He was born into a family of Scottish preachers. His father, James, was a preacher, as were his brothers, Andrew and John. Combined, the Bonars served a total of 364 years as ministers in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Horatius Bonar was as one of eleven children born to a father who was a solicitor (a lawyer). He came to saving faith in Christ early in his childhood, went to the High School and University of Edinburgh, and was licensed to preach in 1833. He did mission work in Leith for a while, and then in 1837 became the minister of the new North Church in Kelso. God blessed Bonar’s ministry greatly and many were added to the Kingdom of God throughout Scotland through his service. He preached the Gospel with authority and passion, with kind sincerity visited his parishioners, and faithfully fasted and prayed for God’s blessing and help.

Bonar was especially dedicated to the children in his church, in the community, and in his Sunday-school classes, where he began composing hymns put to well-known tunes especially for them. It was because of this work that the children were able to participate in worship more happily and readily than if they only sang the metrical psalms used in the Church of Scotland in those days. He loved the children greatly and they grew very attached to him. Sinclair Ferguson has said, “It is a great mark of grace, surely, when a minister of the gospel endears himself to youngsters in this way. For this was also a man who was no shrinking violet and was resolutely opposed to any distortions of the gospel.”

In 1843, Bonar married Jane Catherine Lundie, who was also a hymn writer (she wrote “Fade, Fade, Each Earthly Joy”). Parents of nine, together they experienced terrible hardship and broken hearts when they lost five of their young children in succession. Horatius wrote verses of grief as he watched each little life slip away. God graciously allowed four of their nine children to grow to maturity. Bonar wrote of this as a very great trial of suffering. When in his old age his widowed daughter moved back to the family home with five small children, he saw this as a great blessing from God. Bonar wrote the heart-rending poem “Lucy” in August, 1858 at the death of a daughter.

All night we watched the ebbing life,

As if its flight to stay;

Till, as the dawn was coming up,

Our last hope passed away.

She was the music of our home,

A day that knew no night,

The fragrance of our garden-bower

A thing all smiles and light.

After his daughter moved back home with her children, the love and sweet spirit of the Bonars is truly evident in a letter written to a friend, “God took five children from life some years ago, and He has given me other five to bring up for Him in my old age.” That reminds us of how God restored to Job the number of children that had perished when his afflictions began.

While Bonar’s hymns were initially written for his beloved Sunday school children, adults also treasured his songs, and he continued writing hymns throughout his life for all saints. He wrote over 600 of them, all rather simple in frame, yet beautifully profound in their theological depth. As a hymn writer, a celebrated author, beloved pastor, dear husband, dedicated father and as a saint, Bonar’s desire was to give His God all the honor, glory and praise so that “He must increase, but I must decrease.” (John 3:30). He even requested that no one write a biography about him after his death. Thankfully, we are blessed to have scraps of memories that we can piece together to know more about this pastor whose heart was full of love, poetry and song. At a memorial service following his death, his friend, Rev. E. H. Lundie, said: “His hymns were written in very varied circumstances, sometimes timed by the tinkling brook that babbled near him; sometimes attuned to the ordered tramp of the ocean, whose crested waves broke on the beach by which he wandered; sometimes set to the rude music of the railway train that hurried him to the scene of duty; sometimes measured by the silent rhythm of the midnight stars that shone above him.”

In 1843, at age 35, Horatius became a “come outer” when he joined about 450 other preachers in departing from the Church of Scotland to form the more evangelical Free Church of Scotland. This was a product of the Second Great Awakening with its zeal for the new birth, the infallibility of Scripture, spiritual discipleship, and evangelism. The Free Church preachers wanted greater congregational freedom from government control and the power of the congregations to choose their own ministers. Thomas Chalmers, Horatius’ professor of theology at Edinburgh, was the first Moderator. These zealous ministers gave up their former positions, income, pensions, and manses. They trusted in God alone and were not disappointed. The Free Church went on to establish hundreds of churches and schools. Embracing historic Calvinistic, it had great zeal for evangelistic enterprises, including Sunday Schools, missions to the poor, and overseas missions (including sending David Livingstone to Africa). There was a large response by commoners such as miners, fishermen, and craftsmen.

Bonar preached in the cities as well as in open air campaigns, in farms, villages, and rural schools. One of his contemporaries wrote, “The chief characteristic of his preaching was its strange solemnity. It was full of entreaty and warning. Dr. Bonar exhibited with faithful simplicity and decision the great things of the Gospel, but he was never content without applying them to the consciences of his hearers.” With two other preachers, he witnessed much blessing in village ministries in the countries of Roxburgh, Berwick, and Northumberland. “Whole villages [were] awakened, besides many stray souls, both young and old gathered into the church of God, from various quarters … Many rebuffs we got, many angry letters, many threats of ecclesiastical censure … but, in spite of all this, the work went on.”

Bonar interpreted prophecy in a very literal manner and held to Christ’s pre-millennial second coming. He wrote a commentary on Revelation and several books on prophecy that refuted post-millennialism. He believed the “allegorical interpretation of prophecy” was a harmful thing that had hidden the Blessed Hope from multitudes of Christians. That literalistic interpretation of prophecy gave Bonar his perspective of end-time Christianity. He saw in his own time the apostasy prophesied in Scripture. In a typical sermon he said, “I know not but this may be my last opportunity of bearing witness to the much-forgotten doctrine which was so specially given to the Church as her blessed hope; and I wish to say how increasingly important that doctrine is to me as the ages are running to their close, and the power of the great adversary is unfolding itself both in the church and in the world. … The poison of the last days has penetrated everywhere. Unbelief, error, strong delusion, self-will, pride, hatred of God and of His Christ – these are the deadly forces operating all over the earth, disintegrating society, and demonstrating the necessity for the return of Him who is to end all of Satan’s and man’s evil work, and introduce the kingdom of righteousness and peace”

Bonar warned of the rapid spread of science (falsely so called), philosophy, theological liberalism, and worldliness in British churches in his own lifetime. After 50 years of ministry he wrote, “The changes that have taken place in public opinion, in theological speculation, in ecclesiastical discipline, in religious sentiment; in spiritual thought, in conjectural criticism, in the value attached to belief and non-belief, in the new codes of hermeneutical law and in the rejection of creeds, and in the refusal of any guidance or control save those of science and philosophy, the adoption of culture, and the like, have been immense over these fifty years since my ministry began.”

Horatius Bonar is the most prominent and prolific Scottish hymn writer, and has been called “the prince of Scottish hymn writers.” He authored over 600 poems and hymns, about 140 of which were published. Many are still sung widely today. They focus on the great themes of the infinite sufficiency of Christ’s vicarious atonement, the gospel of grace alone, regeneration, the Trinity, God’s love, Christ’s high priesthood, the trying of faith, confidence in Christ, holiness, surrender and devotion, the comfort of the Spirit, spiritual warfare, and Christ’s return. They include “O Love of God, how Strong and True,” “Blessing and Honor and Glory and Power,” “I Heard the Voice of Jesus Say,” “Here, O My Lord, I See Thee Face to Face,” “I Was a Wandering Sheep,” “No, Not Despairingly, Come I to Thee,” “I Lay My Sins on Jesus,” “The Works, Not Mine, O Christ,” “A Few More Years Shall Roll,” “Go, Labor On, Spend and Be Spent,” “Fill Thou My Life, O Lord My God,” “When the Weary, Seeking Rest,” and “Thy Way, Not Mine, O Lord.” Like all preaching should be, his hymns were all about Jesus!

Though Bonar promoted hymn singing, he warned about the power of “exuberant” hymns and music to create a false sense of spiritual reality in the hearts of the hearers. Such caution is very timely, as we see some of these dangers today, both in classic and in contemporary services. He wrote, “One is often inclined to ask how far some of these exulting hymns may be the utterance of excitement or sentimentalism … hymns are often the channels through which much unreality is given vent to in ‘religious life.’ Song, like music, is often deceitful, making people unwittingly believe themselves to be what they are not. The amount of superficial similarity which has, in all ages, been introduced into and fostered in the Church by music, is incalculable. High-wrought feeling produced by it in conjunction with song, has in many a case misled both the singer and the listener into a belief that their heart was beating truly and nobly towards Christ, when all the goodness was like the morning cloud and early dew.”

There are many religions among the peoples and tribes of this world. Many of those religions sing hymns or chant or offer up words of prayer and praise to their false gods. But there is only one religion in the entire world that can sing the words of the song, “Not What My Hands Have Done.” When we sing this song, we are affirming the truth of Scripture that we have absolutely nothing to offer God, and that salvation, from beginning to end, is achieved through the work of God, not by us (Romans 3:21-25, 5:1-2; 2 Corinthians 5:20; Ephesians 2:1-10; Titus 3:5). We sing, “Thy work alone… Thy blood alone… Thy grace alone… Thy power alone…No other work, save Thine, no other blood will do; No strength, save that which is divine, can bear me safely through!” The religions of the world cannot sing these words, (they would be fairly nonsensical in their opinion) because for them, their salvation is based entirely on either the family they are born into, or how they pray, how often they go to church, the good works they do, how they keep all the rules, or the evil they expel from their lives. Aside from Christianity, every religion in the world is a works or law-based system for attaining some form of salvation for the after-life.

The Scriptures tell us that God requires complete perfection and righteousness to be in His presence. Try as we may, there is no way for us to get rid of all the sin in our hearts, because thanks to our first parents (Adam and Eve) it is part of our very nature. The greatest news ever is that God has made a way for us to be righteous before Him. That way is to rely and trust completely in Jesus for His perfection. The burden is not on us to be good enough, or pray hard enough. We wouldn’t be able to achieve that kind of perfection and holiness even if we tried! Jesus has done it! He is our only hope for righteousness, salvation, and heaven. Praise Jesus! He has made a way! Bonar has expressed that great truth with great clarity and eloquence in this hymn.

Bonar’s original version included twelve stanzas of four phrases each. In modern hymnal settings, they have been edited, with two of the four phrase stanzas being incorporated into a single stanza. Basically, with a few exceptions, that means his stanzas 1 and 2 were combined into a modern first stanza, his stanzas 3 and 4 were combined to become a modern stanza 2, and etc. In another editorial change, hymnals today frequently change phrases like “these” hands (etc.) to “my hands.”

Stanza 1 rules out any work or feeling or religious act that we can do, not even “all my prayers and sighs and tears can bear my awful load.” Nothing we have done counts meritoriously for salvation. Our experiences and hard times do not pay off the tiniest amount of our sin debt. Our emotions, whether positive or negative, are useless. Our actions and good works are counted as nothing, and trash (Philippians 3:8). Our prayers and tears can’t save us at all. There is nothing in us that can help us. We are empty. We have nothing to offer God. To the unbeliever, this is unthinkable, and even offensive in his pride. But to the Christian, there is immense rest here. To be empty before God is to be wholly reliant on the One who can save.

Not what these hands have done can save this guilty soul;

Not what this toiling flesh has borne can make my spirit whole.

Not what I feel or do can give me peace with God;

Not all my prayers, and sighs, and tears, can bear my awful load

Stanza 2 reminds us that our love to God is not enough to “ease this weight of sin” and give me peace within.” We know from sad experience that we do not love God the way He deserves to be loved. In one moment we may be burning in worship and in the next falling for the slightest temptation. We are the definition of fickle and unstable. But the work and blood of Christ cannot fail. We look to the love God has shown to us for salvation; not our shifting love for Him. It is His love to me alone that “can rid me of this dark unrest, and set my spirit free.”

Thy work, alone, O Christ, can ease this weight of sin;

Thy blood alone, O Lamb of God, can give me peace within.

Thy love to me, O God, not mine, O Lord to Thee,

Can rid me of this dark unrest, and set my spirit free.

Stanza 3 is simply incredible, as it points us to the magnificence of divine grace. With all the voices around us that supposedly offer easier ways to heaven, more prosperity, and counterfeit gods that make us feel better about ourselves, we must hold to this truth: only the voice of God has the right to speak to us about our souls. Grace is only found in His promises. We cannot look for it anywhere else. Christ is the only person who can rescue us from the weight of our sins. We must plant our flag on His sacrifice; “no meaner blood will do.” We must have Him! Only this divine grace is strong enough to “bear me safely through.”

Thy grace alone, Oh God, to me can pardon speak;

Thy power alone, Oh Son of God, can this sore bondage break.

No other work, save Thine, no meaner blood will do;

No strength, save that which is divine, can bear me safely through.

Stanza 4 reaches out in the light of the truths that have been stated before and takes a firm hold on Christ and this love divine. Because He has provided all that is necessary for our salvation, because He has done all the work, nothing lacking, we reach out and grasp Him with all our might. If there is any doubt of His love for us, we take one glance at the cross and the “lingering shade of doubt dissolves,” along with “every thought of unbelief and fear.” We take all our unbelief and fear and spiritual depression and stuff it in the dark interior of the empty garden tomb. Sin, self, and Satan have no claim on us.

I bless the Christ of God; I rest on love divine;

And with unfaltering lip and heart, I call this Savior mine.

His cross dispels each doubt; I bury in His tomb

Each thought of unbelief and fear, each lingering shade of doubt.

Stanza 5 maintains the glorious central theme: that salvation is all about what God has done for me, that I am totally unworthy of this grace, and that I contribute nothing but my sins to my salvation, as Luther so famously wrote. “In Him is only good, in me is only ill.” I receive this gift simply by trusting in “His truth and might.” Bonar adds one of the most wonderful benefits for us in this stanza. “He calls me His, I call Him mine.” No human being would dare make that claim, were it not for the fact that He invites us to do so. And when He does this, causing us to be born again (1 Peter 1:3), He not only forgives and adopts me. He uses “my ill” to draw “His goodness forth,” exactly as Joseph told his brothers in Genesis 50:20, “What you meant for evil, God meant for good.”

I praise the God of grace; I trust His truth and might;

He calls me His, I call Him mine, my God, my joy, my light.

In Him is only good, in me is only ill;

My ill but draws His goodness forth, and me He loveth still.

Stanza 6 rejoices in this central truth one more time. It includes a reference to 1 John 4:19, “I love because He (first) loveth me.” That leads to the obvious implication of that, “I live because He lives,” Jesus being the firstfruits of the resurrection” (1 Corinthians 15:20). Bonar has borrowed a phrase from Colossians 3:3, “My life with Him is hid,” as assurance of the lasting security of our redeemed status. While Bonar obviously would not have known the 1961 hymn “Heaven Came Down” by John W. Peterson, the final phrase bears remarkable similarity, as the refrain to Peterson’s hymn read, “My sins were washed away, and my night was turned to day.”

‘Tis He who saveth me, and freely pardon gives;

I love because He loveth me, I live because He lives.

My life with Him is hid, my death is passed away,

My clouds have melted into light, my midnight into day.

The tune LEOMINSTER was written in 1862 by George William Martin (1825-1881). It is often sung today in an 1874 arrangement by Sir Arthur Sullivan. Born in London, Martin became a chorister at St. Paul’s Cathedral under William Hawes, and also at Westminster Abbey at the coronation of Queen Victoria. He became a professor of music at the Normal College for Army Schoolmasters, and was from 1845-1853 resident music-master at St. John’s Training College, Battersea, and was the first organist of Christ Church, Battersea in 1849. In 1860 he established the National Choral Society, which he maintained for some years at Exeter Hall, having an admirable series of oratorio performances. He edited and published cheap editions of these and other works not readily available to the public. He organized a 1000-voice choir at the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. He had an aptitude for training children and conducted the National Schools Choral Festival at the Crystal Palace in 1859. As a composer his genius was in directing madrigal and part song, and in 1845 his prize glee “Is She Not Beautiful?” was published. “Due to intemperance” he sank from a position that gave him notoriety in the elements of musical force in the metropolis. He composed tunes, canticles, and motets. He died quite destitute in a hospital at Wandsworth, London. No information about his family has been found.

Here is a link to the congregational singing of the hymn from Washington, DC’s Capitol Hill Baptist Church, using the lyrics as usually printed today, omitting the sixth stanza, which is rarely included in recent times.