In Revelation 4 and 5, we are privileged to read the actual words that are continuously being sung in heaven by the saints and angels, gathered in concentric circles around the throne of God. The song, in three slightly different variations, is found in 4:11, 5:9-10, and 5:12. In all three, the common denominator is the word “worthy” as a description of Jesus, the Lamb of God. The Greek word for worthy, axios, is a word that indicates not only value, but also authority, majesty, and power, as well as of great importance and influence.

The scroll that the apostle John saw in that amazing Lord’s Day vision was written on both sides, likely symbolizing the full details of all that God has planned from eternity for the history of redemption, both in this life and on into eternity. John observed that it was sealed with seven seals (seven being the number of total fullness), implying that its contents – God’s plans – were sealed, awaiting someone who would be found “worthy” to open its seals, and therefore accomplish these divine redemptive plans.

And then comes one of the saddest moments in all of Scripture. After a mighty angel asked, “Who is worthy to open the scroll and break its seals?” no one in heaven or on earth or under the earth was found who was able to open the scroll. At that news, John began to weep loudly, because that meant that God’s saving work could not be accomplished. Creation history would descend into deeper and deeper hopelessness, and come to end in total emptiness and futility, with all of humanity forever banished from God’s loving presence. All the anguished cries of people suffering under the ravages of sin would forever go unanswered, and with no relief.

But then John hears the good news. “One of the elders said to me, ‘Weep no more; behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that He can open the scrolls and its seven seals.’” At that, John saw “a Lamb standing as though it had been slain.” And that’s what prompted that glorious chorus that follows, the chorus that Handel used at the conclusion of Messiah.

“Worthy are You to take the scroll and to open its seals, for You were slain, and by Your blood You ransomed people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation, and You have made them a kingdom and priests to our God, and they shall reign on the earth.”

Then I looked, and I heard around the throne and the living creatures and the elders the voice of many angels, numbering myriads of myriads and thousands of thousands saying with a loud voice, “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!”

And I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and in the sea, and all that is in them, saying, “To Him who sits on the throne and to the Lamb be blessing and honor and glory and might forever and ever!”

And the four living creatures said, “Amen!” and the elders fell down and worshiped.

The great theme of this opening vision in Revelation is this: “Worthy is the Lamb.” Jesus is the center of God’s revelation of Himself in history (“If you have seen Me, you have seen the Father,” John 14:9). Jesus is the center of God’s work of redemption, and also then the center of the worship of heaven. We give to Him this kind of exalted praise because He is infinitely “worthy” of such adoration and adulation.

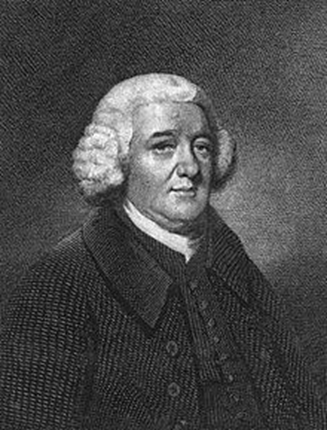

We are not all capable of singing Handel’s “Worthy Is the Lamb,” but we can certainly all sing the hymn, “O Could I Speak the Matchless Worth.” It was written by an Englishman, Samuel Medley (1738-1799), who was born at Cheshunt, Hertfordshire, where his father was tutor to the Duke of Montagne, and later ran his own school. He received a good education, in part from his grandfather, William Tonge, an Enfield teacher and a deacon at Andrew Gifford’s church in Holborn. At the age of 14 he was apprenticed to an oilman in the city of London, but found that to be less than satisfying.

In 1755 war broke out between England and France and a law was quickly passed allowing apprentices to complete their indentures in the Royal Navy. To Medley this seemed like the perfect answer to his unhappy situation. He could then be like his two older brothers, whom he had often envied. He too then determined to pursue a glorious naval career.

And so at the age of 17, we find him aboard the 74-gun Royal Navy ship The Buckingham. The ship’s captain had also been a pupil of Medley’s grandfather and as Medley was full of enthusiasm, he did what he could to further his career. Soon the captain and officers transferred to a similar ship called The Intrepid and Medley was made Captain’s mate. The Intrepid was active in the Mediterranean for the next few years. During this time Medley gladly had many opportunities to improve his education, but also, sadly, to go on in the path of sin to which he had grown increasingly accustomed, as with many sailors in those days. Despite his Christian upbringing, he soon forgot what he had been taught. With scarce a thought for serious matters, he continually sought out the pleasures of sin.

Things continued in this vein until he reached the age of 21. In 1759, an important sea battle was fought on the Portuguese Coast near Port Lagos. It was Medley’s job to sit on board and write down details of the action between the English and French fleets. It was a bloody battle. It is said that there was so much blood spilt that the French used barrels of flour on the decks to save people from slipping over. As the battle progressed a cannon ball shattered the mizzen-mast close to where Medley was. Shortly after that he saw a wounded soldier being carried by one of his shipmates. A cannon ball hit both and they fell into the hold below.

Then suddenly the mate cried out to him that he, Medley, had been wounded. Medley had not realized it until his attention was called to the fact. A large part of his leg had been shot away and he was in serious condition. He had to be helped to walk to the surgeon. He had lost a great deal of blood. The British were victorious in the battle, but Medley was unwillingly confined to his bed. Fired by this victory, his ambition ran high, but the leg did not heal properly, and he became quite depressed about the situation.

After some time, the ship’s surgeon had to inform him that there was gangrene and that his leg would have to be amputated. This was something of a shock to the wild young man, but remembering his grandfather and father’s example, he thought he had best pray. He had been leading a very profligate life, but hoped that perhaps it was not too late. He remembered that he had seen a Bible in his storage chest and sent a servant to get it. All that night he read the Word and prayed that the Lord would save his leg. Most unexpectedly, by the next morning his leg was found to be healing. Quite a change came about in Medley, but before he had recovered he began to fall into old habits. He eventually returned home to stay with his grandfather, who would often read to him from the Scriptures and encourage him to seek the Lord. One evening he read a sermon by Isaac Watts on Isaiah 42:6, 7, “I am the Lord; I have called you in righteousness; I will take you by the hand and keep you; I will give you as a covenant for the people, a light for the nations, to open the eyes that are blind, to bring out the prisoners from the dungeon, from the prison those who sit in darkness.” It was this passage that God used to finally bring him to salvation.

He joined the Baptist Church in Eagle Street, London, then under the care of Dr. Andrew Gifford (1700-1784), pastor of that Baptist congregation, beginning in 1730. Shortly afterward, Medley opened a school, which for several years he conducted with great success. Having begun to preach, in 1767 he received a call to become pastor of the Particular Baptist church at Watford. Thence, in 1772, he moved to Byrom Street, Liverpool, where he gathered a large congregation, and for 27 years was remarkably popular and useful. He had a very happy and effective ministry, especially among the many seafarers with whom he came into contact. The year after his arrival the building had to be extended, and in 1789 a new and enlarged chapel was erected.

In his latter years, Medley’s health declined and on his annual trip to preach in London in the autumn of 1798 his condition became much worse. After a long and painful illness he eventually died in Liverpool on July 17, 1799. In his last illness he wrote for himself an epitaph in Latin which has been translated,

An unworthy preacher of the gospel,

formerly pastor of this church of Christ,

by nature and practice a miserable sinner,

but redeemed by grace and the blood of the Savior,

has here laid down his body,

waiting for the bright and morning star.

Come then Lord Jesus.

Dying at the age of sixty-one, he joyfully exclaimed on his deathbed: “I am now a poor shattered bark, just about to gain the blissful harbor; and O how sweet will be the port after the storm! Dying is sweet work, sweet work. I am looking to my dear Jesus, my God, my Portion, my All in All. Glory! Glory! Home! Home!”

Medley is best remembered today as a hymn writer. His most enduringly popular is “O Could I Speak the Matchless Worth.” His hymns first appeared in pamphlet form, but from 1785 some began to appear in bound volumes. Later in life a collection of 230 of his hymns of varying quality appeared. Writing that our wonderful Savior is infinitely worthy of our praise, Medley saw the “matchless worth,” and “glories…which…shine” in the Lord Jesus Christ. So precisely what is it that Medley considered worthy of his songs of thanksgiving and worship? Three things in particular stand out. First, there is the blood-bought ransom Christ paid to deliver him from the “dreadful guilt” incurring God’s holy wrath. The wonder of the work of salvation is twofold, in that something is removed and something added. Not only are we forgiven, with our debt of sin paid, but also we are credited with the “glorious righteousness” of Christ (stanza 2). Second, there’s the holy character of Christ to celebrate. Several times the Bible asserts that He is totally without any taint of sin. But even more than that, Christ is said to represent on earth, in human form, all the perfections of God’s character (stanza 3). Finally, there’s the glorious prospect that one day believers will be ushered into the presence of Christ, and enjoy eternal fellowship with the Savior.

Stanza 1 gives praise for Jesus’ numberless glories, as we sing His matchless worth when we say with the angels, “Worthy is the Lamb” (Revelation 5:11-12). Some modern editors, apparently not liking the symbolism, have changed the latter part of the stanza to say, “I’d sing His glorious righteousness, And magnify the wondrous grace Which made salvation mine.” Some among us might object to speaking of “the heavenly strings,” but the book of Revelation does, symbolically, refer to heavenly beings as playing the strings of harps, as a symbol of the beauty of the praise offered to God, and the song simply uses the same language to express the author’s wish that he could join with them (Revelation 14:1-2). Medley assumed that since Gabriel is an angel, he would be joining the chorus of praise around the throne of Christ, so he expresses his wish to join him (Daniel 8:16; 9:21; Luke 1:19, 26).

O could I speak the matchless worth,

O could I sound the glories forth

Which in my Savior shine,

I’d soar, and touch the heav’nly strings,

and vie with Gabriel while he sings

in notes almost divine, in notes almost divine.

Stanza 2 gives praise for Jesus’ precious blood. Jesus “spilt” that blood that we might have redemption (Ephesians 1:7). Some object to the word “spilt” with reference to Jesus’ blood, saying that it implies something accidental such as spilling milk, but that is not always the case. At a dam, sometimes the operators intentionally “spill” water into a “spillway” to avoid flooding. In fact, Webster’s New International Dictionary, Second Edition, defines spill, “To cause or allow intentionally to flow out and be lost or wasted; to shed, as blood.” This blood is not wasted, but is our ransom from the dreadful guilt of sin (Matthew 20:28). This blood also makes it possible for us to be clothed in His glorious righteousness (Zechariah 3:3-4). This can be understood to refer to the righteousness which He Himself reckons to our account, and is not our own but is given to us by Him as that “alien righteousness” of which Luther wrote (Romans 4:6; Philippians 3:9).

I’d sing the precious blood He spilt,

my ransom from the dreadful guilt

of sin, and wrath divine:

I’d sing His glorious righteousness,

in which all perfect, heav’nly dress

my soul shall ever shine, my soul shall ever shine.

Stanza 3 gives praise for the multiple dimensions of Jesus’ characters (plural), apparently referring to different qualities exhibited by Christ, or perhaps different roles in which He functions. Whichever is the case, His character is determined by all the forms of love that He wears (Ephesians 5:2). His character is also demonstrated by the fact that He has been exalted on His throne (Acts 2:30-33). We “sing the character He bears” when we “make all His glories known” (John 1:14), as well as when we grow in the fruit of the Spirit (Christ-likeness) that Paul described in Galatians 5:22-23.

I’d sing the characters He bears,

and all the forms of love He wears,

exalted on His throne:

in loftiest songs of sweetest praise,

I would to everlasting days

make all His glories known, make all His glories known.

Stanza 4 gives praise for Jesus’ triumphant coming again. The original began “Soon,” but while “soon” could refer to the time of death when the Lord will bring us home, the stanza seems to be referring more to the time of the second coming, which no one knows, so many books change it to “Well” (Matthew 24:36). Even though we do not know when, we do know that someday, the Lord will come to raise the dead, change the living, and take us home to be with Him (1 Thessalonians 4:16-17). Then we shall have the blessed privilege of seeing His face in that “beatific vision” (1 John 3:1-3), the one we will forever know as our “Savior, Brother, Friend.” What an incredible joy and privilege awaits us!

Well, the delightful day will come

when my dear Lord will bring me home,

and I shall see His face;

then with my Savior, Brother, Friend,

a blest eternity I’ll spend,

triumphant in His grace, triumphant in His grace.

Originally in eight stanzas beginning, “Not of terrestrial mortal themes,” the modern version consists of stanzas 2, 4, 6, and 8, omitting these four.

Stanza 1:

Not of terrestrial mortal themes,

Not of the world’s elusive dreams

My soul attempts to sing;

But of that theme divinely true,

Ever delightful, ever new,

My Jesus and my King, My Jesus and my King.

Stanza 3:

Upon the theme I’d ever dwell,

And in transporting raptures tell

What I in Jesus see;

I’d sing with more than mortal voice,

And lose my life amid the joys

Of what He is to me, if what He is to me.

Stanza 5:

Prostrate before His throne I’d fall,

And bless His holy name for all

The riches of His grace:

I’d sing how glorious power subdued,

I’d sing, how sovereign love renewed

The vilest of the race, the vilest of the race.

Stanza 7:

But ah! I’m still in clay confined,

And mortal passions clog my mind,

And downward drag me still:

O when shall I attain the skies,

And to immortal glories rise

On Zion’s heavenly hill, on Zion’s heavenly hill.

The tune ARIEL is usually attributed to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791). If he did compose it, its origin among his works has never been found. This arrangement was made by Lowell Mason (1792-1872). It was first published in his 1836 “Occasional Psalm and Hymn Tunes.” Born at Salzburg, Austria, the son of Leopold Mozart, a minor composer and violinist, and youngest of seven children, Mozart showed amazing ability on violin and keyboard from earliest childhood, even starting to compose music at age four when his father would play a piece and Mozart would play it exactly as did his father. At five, he composed some of his own music, which he played to his father, who wrote it down. When Mozart was eight, he wrote his first symphony, probably transcribed by his father. In his early years his father was his only teacher, teaching his children languages and academic subjects, as well as fundamentals of their strict Catholic faith. Some of his early compositions came as a surprise to his father, who eventually gave up composing himself when he realized how talented his son was.

Mozart’s career led him on concert tours through many of the royal courts of his day, and into friendships with Bach and Handel. His choral, orchestral, and piano works remain in standard classical repertoire today. He was a composer of operas, as well. For many, he is best known for his “Requiem,” made famous through the 1984 movie “Amadeus.” In his later years, he fell into debt and started pawning valuables. During these events his mother died. In 1782 he married Constanze Weber Mozart Nissen. The marriage started out with a brief separation, and there was a problem getting Mozart’s father’s permission, which finally came. They had six children, but only two survived infancy: Carl and Franz. He lived in Vienna and achieved some notoriety, composing many of his best-known symphonies, concertos, and operas there.

In 1791, while in Prague for the premiere of his opera, “La clemenza di Tito,” he fell ill. He continued professional functions for a short time, but had to go home and be nursed by his wife over the next couple of months. He died at Vienna, Austria, at the age of only 35, a small thin man with undistinguishing characteristics. He was buried in a modest grave, having had a small funeral. As a side note, Mozart enjoyed billiards, dancing, and had a pet canary, a starling, a dog, and a horse for recreational riding. He liked off-color humor. He wore elegant clothing when performing and had a modest tenor voice.

It was Lowell Mason, the father of America’s music education and of American church music, who arranged the Mozart music into the present hymn form. He was born in Medfield, Massachusetts on January 8, 1792. From childhood he had manifested an intense love for music, and had devoted all his spare time and effort to improving himself according to such opportunities as were available to him. At the age of twenty he found himself filling a clerkship in a banking house in Savannah, Georgia. After some time in church music at the Independent Presbyterian Church in that city, he accepted an invitation to move to Boston and enter more fully upon a musical career. This was in 1826.

The next year Mason became president and conductor of the Handel and Haydn Society. It was the beginning of a career that was to win for him, as has been already stated, the title of “The Father of American Church Music.” He visited a number of the music schools in Europe, studied their methods, and incorporated the best things in his own work. He founded the Boston Academy of Music. The aim of this institution was to reach the masses and introduce music into the public schools. Mason resided in Boston from 1826 to 1851, when he moved to New York. Not only Boston benefited directly by this enthusiastic teacher’s instruction, but he was constantly traveling to other societies in distant cities and helping their work. Mason died at “Silverspring,” a beautiful residence on the side of Orange Mountain, New Jersey, August 11, 1872, bequeathing his great musical library, much of which had been collected abroad, to Yale College.

Here is a link to Medley’s text with the Mozart tune as arranged by Mason, sung in English by a Chinese Christian choir.