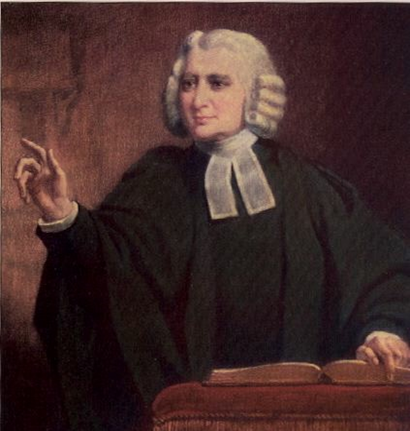

“O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing” was written by Charles Wesley when he was just one year old! One year old in the Lord, that is. He penned this classic hymn a year after his conversion. He gave it the title, “For the Anniversary Day of One’s Conversion.” Filled with great enthusiasm about the experience – and doctrine – of regeneration, it thrills the heart of every person who has been born again to new life in Jesus Christ. One study found that this hymn is found today in more than 1600 hymnals! He would go on to write more than 6500 hymns.

The story of the conversion of the Wesley brothers, John and Charles, in 1738 is one of the best known personal accounts of the doctrine and experience of being born again. That phrase, of course, comes from John 3:3 where, in their evening meeting, Jesus told Nicodemus, “unless one is born again he cannot see the kingdom of God.” This is the Spirit’s work of regeneration, and is the distinguishing mark of the essence of biblical Christianity. A Christian is not someone who has done something for God, but someone for whom and in whom God has done something. As we read in 1 Peter 1:3, it is God who “has caused us to be born again to a living hope.”

The early eighteenth century was not a time marked by health and vitality in the Church of England. Alcohol abuse, gambling, and immorality were common in the cities of the nation. It was reported that in many neighborhoods, every other structure was a rum house. Broken homes and poverty added to the plight of residents. The church was led by men of mediocre spirituality, at best. Ritualism dominated the services and baptism was assumed to guarantee eternal life, regardless of the lack of heart devotion to Christ or obedience to His Word in the years that followed.

It was into such a society that Charles Wesley was born in 1707. He was one of nineteen children born to Samuel and Susanna Wesley. Even though he was an Anglican priest, Samuel was a terrible husband and father, sadly remembered for his abuse of his wife and children. Charles and his brother John felt a strong attraction to spiritual things in their teen years. Both attended Oxford University to pursue studies that would lead to their both being ordained as Anglican priests. While there they joined with several other students, including George Whitefield (who later became a well-known evangelist) to form what they called the “Holy Club.” They covenanted together to cultivate the disciplines of spiritual life: Bible study, prayer, journaling, and frequent communion.

Following their graduation and ordination, John and Charles sailed to the colony of Georgia where they engaged in preaching and attempts to improve the conditions of residents. Charles was secretary to Governor Oglethorpe. After less than a year in that work, they set sail for their home in London. In transit, they encountered what sounds today like a hurricane. Experienced sailors were terrified and lashed themselves to masts to avoid being swept overboard. Yet in the midst of the storm’s fury, the Wesleys saw a group of Moravians praying and singing together. It was obvious that they did not have the fear of death that the Wesleys were experiencing. After the storm abated and they were back on solid ground, that memory did not fade.

Back in England, Charles came under the influence of Zinzendorf and the Moravians, which led to his studying under the Moravian scholar Peter Böhler. Wesley was continuing to struggle with severe doubts about his faith. In May of 1738 he was bedridden with pleurisy. A group of Christian friends visited on Sunday afternoon May 21 to encourage him with scripture and prayer. After they had gone, he spent time reading his Bible and in thought and prayer. The Spirit of God worked in his heart to bring clarity to his understanding of the gospel, and he was born again. He wrote these words in his journal. “I was composing myself to sleep in quietness and peace when I heard one come in and say, ‘In the name of Jesus of Nazareth, arise, and believe, and thou shalt be healed of all thine infirmities.’ The words struck me to the heart. I lay musing and trembling. With a strange palpitation of heart, I said, yet feared to say, ‘I believe, I believe!’”

That experience was woven into the words of the hymn that he composed a year later to celebrate that anniversary.

Jesus! The name that charms our fears, that bids our sorrows cease;

‘Tis music in the sinner’s ears, ’tis life, and health, and peace.

Just days later, on May 24, his brother John experienced that same new birth after attending what we would call a home Bible study on Aldersgate Street, not far from St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. They were examining Luther’s preface to his commentary on Romans. John wrote in his journal about the Moravian preacher leading the study, “while he was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt that I did trust in Christ … ; and an assurance was given me that He had taken away my sins.”

Until that point in their lives, both John and Charles had been trusting in their own merits, their own good works, their own morality, their own work as clergymen. Transferring their trust to Christ changed all that. It also changed them. And it certainly changed their preaching and ministry from that point on. They preached the need for conversion, a message which was much needed, but not welcomed by many of the clergy of their day. Bishops forbade the preaching of these “enthusiasts,” as they were labeled. Having been barred from the pulpits of the churches, they preached in the streets and in the fields. Thousands gathered to hear them and they brought new life only to their communities but even to the culture. This was the beginning of one of the greatest revivals in church history, known today as the “Great Awakening.”

Many of the hymns that Charles wrote were for singing in these open air preaching occasions. Some have even suggested that more people were converted by his hymns than by his preaching. That may be true in part, since most of the preaching was done by his brother, John. Charles’s hymns have become a staple in the song life of the church, with a healthy number of his compositions present in every hymnal. Not surprisingly, Methodist hymnals often have “O for a Thousand Tongues” as number one in their collection. According to several scholars, this famous opening line may have been inspired by Charles’ spiritual mentor, German-born Moravian missionary Peter Böhler, who said, “Had I a thousand tongues, I would praise Him with them all!”

Isaac Watts, often called the father of English hymnody, had earlier provided 600 Psalm paraphrases and original hymns. His poetry tended to be more objective, doctrinal expositions in comparison to the more subjective descriptions of personal Christian experience found in Wesley’s hymns. Wesley’s poetic responses to his own conversion are filled with literary excellence and beautiful language. He employed hyperbole right from the start with the description of “a thousand tongues” to heighten the emotional impact of the text. To further intensify the emotional nature of the poem, Wesley punctuates words like “Jesus” and the last words of phrases with an exclamation point. Other poetic devices used to express the incredible nature of salvation include the oxymorons present in stanza six.

Hear Him, ye deaf; His praise, ye dumb, your loosened tongues employ;

Ye blind, behold your Savior come, and leap, ye lame, for joy.

Wesley used antithesis throughout to contrast the darkness of sin with the light of the atoning blood that heals and humbles our hearts, and replaces our fears with the rejoicing for a new life. This contrast underscores the nature of Wesley’s own conversion.

Charles not only wrote thousands of hymns, many of them were included in hymnals published during his lifetime. Such collections included “Hymns on God’s Everlasting Love” (1742), “Hymns on the Lord’s Supper” (1745), “Short Hymns on Select Passages of the Holy Scriptures” (1762), and “Hymns and Prayers to the Trinity,” as well as others celebrating the major festivals of the Christian year. Beyond that, his poetry included epistles, elegies, and political and satirical verse.

In April of 1749, he married the much younger Sarah Gwynne, also known as Sally. While they lived in Bristol, she would accompany the Wesley brothers on many of their preaching tours. In 1771 the whole family moved to London where they remained until Charles’s death in 1788. Only three of the couple’s eight children survived infancy. Both Samuel and Charles junior were musical child prodigies and became organists and composers. And Samuel’s son, Samuel Sebastian Wesley, was one of the foremost British composers of the 19th century. On Charles Wesley’s deathbed, he sent for the Rector of St. Marylebone Parish Church, John Harley, and purportedly told him, “Sir, whatever the world may say of me, I have lived, and I die, a member of the Church of England. I pray you to bury me in your churchyard.” He died at the age of 80 on March 29. His body was carried to the church by six clergymen of the Church of England. A memorial stone to him stands in the gardens in Marylebone High Street, close to his place of burial. His son, Samuel, became the organist of that church.

The original hymn had 18 stanzas. The seventh stanza became the first stanza of the hymn that we now know.

Stanza 1 describes our wish that we actually had a thousand tongues to sing Jesus’ praise. Notice Wesley’s focus is not only on our Redeemer’s glory and triumph in saving us by His grace, but more on our experience in celebrating that triumph in song.

O for a thousand tongues to sing my great Redeemer’s praise,

The glories of my God and King, the triumphs of His grace.

Stanza 2 is directed to the Lord, asking that He would assist us in that celebration, and that He turn it into a proclamation of the gospel “through all the earth.” Here we see Wesley the evangelist, not just rejoicing in his own salvation, but longing that others would be brought to faith as well.

My gracious Master and my God, assist me to proclaim,

To spread through all the earth abroad, the honors of Thy name.

Stanza 3 recalls the moment of conversion when a person realizes who Jesus is and what He has done. Here are 3 things that name accomplishes: it charms our fears (which are many!), bids our sorrows cease (which are painful!), and becomes music in our ears, giving life, health, and peace.

Jesus, the Name that charms our fears, that bids our sorrows cease;

‘Tis music in the sinner’s ears, ‘tis life, and health, and peace.

Stanza 4 points us to the cross where the blood of Jesus has set us free from bondage to sin and washed us from the filth of our sin. Wesley wrote of “cancelled” sin, but some hymnals have changed it to “reigning” sin. Cancelling sin is not exactly what Jesus has done; He conquered it.

He breaks the power of reigning sin, He sets the pris’ner free;

His blood can make the foulest clean, His blood availed for me.

Stanza 5 is a description of Wesley’s own experience, and that of everyone who has been born again in adulthood. We were dead in our sin, and He has raised us to new life (Ephesians 2). We mourn over sin no longer as He heals our broken hearts, and takes away our spiritual poverty.

He speaks and, listening to His voice, new life the dead receive;

The mournful broken hearts rejoice; the humble poor believe.

Stanza 6 is a powerful statement of what the gospel has done. The deaf hear, the dumb speak, the lame leap, the blind see. All this recalls Jesus’ healing ministry as His miracles were pictures of salvation, giving spiritual hearing to the deaf, spiritual speech to the dumb, spiritual sight to the blind, spiritual mobility to the lame.

Hear Him, ye deaf; His praise, ye dumb, your loosened tongues employ;

Ye blind, behold your Savior come; and leap, ye lame, for joy.

When we sing this, it’s almost like having Wesley himself in our church giving his testimony!

The music we use, named AZMON, was written by the American church musician Lowell Mason (1792-1872), based on a composition by the German musician, Carl Gotthelf Gläser (1781-1829). Mason wrote AZMON specifically for this Wesley text. He composed or arranged the music for many other the well-known hymn tunes we sing regularly, including the music for “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross,” “Joy to the World,” and “There Is a Fountain Filled with Blood.”

Here is a recording of the hymn as sung at Grace Community Church in California.

Wesley’s text is often sung in the UK to the wonderful tune LYNGHAM, as you can listen below. It is a very energetic setting, well-suited to Wesley’s theme.

O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing (Complete Text)

- Glory to God, and praise and love,

Be ever, ever given;

By saints below and saints above,

The Church in earth and heaven. - On this glad day the glorious Sun

Of righteousness arose,

On my benighted soul he shone,

And filled it with repose. - Sudden expired the legal strife;

‘Twas then I ceased to grieve.

My second, real, living life,

I then began to live. - Then with my heart I first believed,

Believed with faith divine;

Power with the Holy Ghost received

To call the Saviour mine. - I felt my Lord’s atoning blood

Close to my soul applied;

Me, me he loved – the Son of God

For me, for me he died! - I found and owned his promise true,

Ascertained of my part,

My pardon passed in heaven I know,

When written on my heart. - O For a thousand tongues to sing

My dear Redeemer’s praise!

The glories of my God and King,

The triumphs of His grace! - My gracious Master and my God,

Assist me to proclaim,

To spread through all the world abroad

The honors of Thy name. - Jesus! the Name that charms our fears,

That bids our sorrows cease;

‘Tis music in the sinner’s ears,

‘Tis life, and health, and peace. - He breaks the power of cancell’d sin,

He sets the prisoner free;

His blood can make the foulest clean,

His blood avail’d for me. - He speaks, – and, listening to his voice,

New life the dead receive;

The mournful, broken hearts rejoice;

The humble poor believe. - Hear him, ye deaf; his praise, ye dumb,

Your loosen’d tongues employ;

Ye blind, behold your Saviour come,

And leap, ye lame, for joy. - Look unto him, ye nations; own

Your God, ye fallen race;

Look, and be saved through faith alone,

Be justified by grace. - See all your sins on Jesus laid;

The Lamb of God was slain;

His soul was once an offering made

For every soul of man. - Harlots, and publicans, and thieves,

In holy triumph join!

Saved is the sinner that believes,

From crimes as great as mine. - Murderers, and all ye hellish crew,

Ye sons of lust and pride,

Believe the Savior died for you;

For me the Saviour died. - Awake from guilty nature’s sleep,

And Christ shall give you light,

Cast all your sins into the deep,

And wash the AEthiop white. - With me, your chief, ye then shall know,

Shall feel your sins forgiven;

Anticipate your heaven below,

And own that love is heaven.