Because God is the God of perfect justice, we who have been made in His image have an innate longing for justice. In fact, without a belief in the existence of this God and the moral law He has established, there is no explanation for the source of this longing for justice found in human hearts. Apart from that awareness, how is it that in every culture and in every age, there has been a concept not merely of right and wrong, but more specifically of justice? In many instances it may be perverted and imperfectly applied, but it’s always been there. When we hear a news story about some terrible thing that has been done to an individual, we feel frustrated if the guilty party/parties are not apprehended and prosecuted. This is true in the case of the career criminal, the drunken driver, the mean-spirited employer, the bribe-taking lawmaker, the child-abuser, the unfaithful spouse, the mean-spirited racist, or the wicked totalitarian government that brutalizes its citizens and invades its neighbor’s land.

But we live in a world where justice is all too often beyond our grasp. We see wickedness go without retribution. Governments and law enforcement agencies will repeatedly fail us, leaving us with a sense that things are unfinished, wondering if the guilty will go unpunished. In fact, we too often see the evil doer not only “get away with it,” but even succeed and prosper, while the righteous suffer, as in Psalms 37 and 73. We are left wondering if justice will ultimately prevail, and if the guilty will ever be held accountable. But God’s Word tells us that that will definitely happen. We cry out, along with the souls of the martyrs under heaven’s throne, “How long, O Lord?” (Revelation 6:9). But then we remember the words of Ezekiel 34:7 where God promises that “He will by no means leave the guilty unpunished.” So we patiently await that day, in the words of the hymn, “Whate’er My God Ordains Is Right.”

God has given us a number of Psalms which we can sing to call out to Him for justice. A number of these are in the context of imprecatory Psalms. In fact, 15 of the 150 Psalms (that’s 10% of the entire Psalter!) are of this sort. In these, God has given us inspired words to call on Him to judge those who have set themselves against Him, against His anointed, and against His people. Too many Christians feel embarrassed to pray (or sing) these Psalms. They seem to be contrary to the spirit of love in the New Testament. But God’s love and God’s justice are never set against each other. Both are true of Him, and we should sing and pray about both in our worship.

When we are regularly singing the Psalms in our worship, we will find texts that give expression to this matter of our longing to see divine justice administered. Psalm 5 is one such text, and we have this in the hymn “O Jehovah, Hear My Words.” This falls into the more specific category of “Psalms of Lament,” and is one of about sixty such Psalms, as we cry out to God to hear us in the midst of the trouble that is being forced upon us by those who are enemies of the gospel. They are described in harsh terms concerning their character and their actions, qualities that clearly indicate they have taken their stand as enemies of God Himself.

As commentators have noticed, there is a common pattern to such Psalms of lament, a pattern we find in Psalm 5. They typically begin with an introductory address to God, a petition that asks Him to hear the complaint we bring (1-3). Then comes a more specific description of the complaint itself, and the sense of lament that this creates within our hearts (4-6). Following that, there comes an earnest petition for salvation from our foes, with the confidence that a just God must respond in order to be true to His righteous character (7-8). Next is the particular request we make, asking God to judge them by imposing on them the judgment they deserve (9-10). Finally, the Psalm concludes with public praise in the confidence that God will hear and respond, even if we don’t see it yet (11-12).

Psalms 3, 4, and 5 are traditionally identified as Psalms of David, the first having been composed at the time of the coup led by his son, Absalom. Psalm 3 therefore seems to be David expressing his feelings as he was confronted on that first morning by that terribly painful situation, as his own son had become his mortal enemy. That would make it not merely “a morning psalm,” but the next morning after this happened, making this as gloomy a day as the one before. This marked the first full day of his exile, writing Psalm 4 as an evening psalm as that day ended. Then with Psalm 5 he awoke again to see the same situation, but now with more mature thoughts about it all. He sees in this Psalm the broader scene of God’s opponents, not just his. All five stanzas of Psalm 5 are rightly directed to God. David begins with seven ways of describing these bad people, and then six ways of describing what God thinks of them.

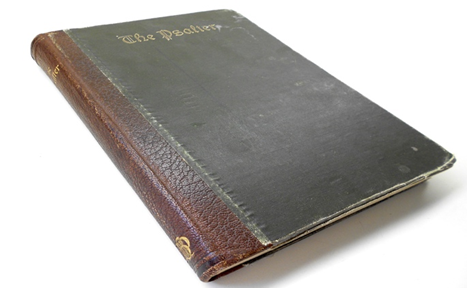

The metrical setting of this Psalm we consider here as “O Jehovah, Hear My Words,” comes from the 1912 “Psalter,” which has been the source of many of the Psalms used in Reformed psalters and hymnals throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries. A metrical Psalm is one which has been translated from the original Hebrew into a contemporary language, following as closely as possible the inspired words of Scripture, but cast into poetic form with balance in the rhyming words and rhythmic phrases that we are accustomed to finding in English poetry. This involves much more than simply writing a hymn based on a few phrases and basic themes of the Psalm. The goal is to be able to sing God’s words in our own language as closely and literally and smoothly as possible.

It was the desire of the creators of that “Psalter” that the singing of Psalms should have a significant, even if not dominant place in the corporate worship of the church, as well as in the hearts of believers. In the introduction to the 1912 “Psalter,” the committee articulated these goals.

- The Christian church should sing all of the psalms—not just a few praise choruses based on single out-of-context verses.

- The Psalms should function as well-crafted poetry, and versifications and tunes must be chosen to bring out this poetry most faithfully.

- The selection of appropriate tunes for each psalm is extremely important; considerations of suitability, quality, familiarity, and longevity must all be taken into account.

- The pair of psalm and tune must be treated as a unit, for the benefit of the congregations and the integrity of the setting.

Here is the on-line description of the process by which this classic 1912 “Psalter “came into being.

By the early 20th century, there had been a long-felt desire for a version of the Psalms which would satisfy modern literary standards and be recognized as the mutual property of the Presbyterian family in Canada and the United States.

Prior to the publication of this joint-venture Psalter, it is unclear exactly what songbooks were in use in the various Reformed denominations. Presumably, many of them had individual collections at their disposal, but the need was growing for a single psalter—a valuable contribution to the interdenominational unity of the churches. An earlier psalter was published in 1887, which laid the groundwork for the 1912 “Psalter.” Still, a solid “modern” source of psalm settings was urgently needed.

It was in 1893 that the United Presbyterian Church first appointed a committee to propose the creation of a new psalter to the various denominations with which it had ecumenical relations. The work commenced, continuing slowly but steadily over the next twelve years. The preface reports, “The Committee of the United Presbyterian Church, increased and definitely instructed by the General Assembly of 1905, set itself very earnestly to its duty, proposing practically a new metrical translation of the Psalms. In 1910, the completed collection of songs was officially adopted as “The Book of Praise of the United Presbyterian Church of North America.” But the work of the committee was not yet done; a complete psalter still needed to be compiled and prepared for publication. The finished product was eventually published at the end of 1912.

The principles outlined in this preface were thoroughly applied to the creation of the 1912 “Psalter”. The result was a songbook that has been widely used, even to this day, by Reformed denominations such as the Free Reformed Churches of North America (FRCNA), the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America (RPCNA), and the Heritage Reformed Churches (HRC).

But the story continues. Twenty years later, the synod of the Christian Reformed Church commissioned a revision of the 1912 “Psalter” which would include not only contributions from the “Genevan Psalter,” but for the first time a collection of hymns as well. The result was the 1934 “Psalter Hymnal.” Later editions of the CRC’s songbook, including the familiar 1959/1976 version from which we sing today, were simply revisions of this modified “Psalter.” Selections from the 1912 songbook are still common even in the CRC’s current (1987) “Psalter Hymnal;” a few of these psalm-hymns have made it into the hymn section of the proposed URC “Psalter Hymnal” and I have no doubt that plenty more will be included among the psalm settings. From this brief historical summary, it is clear that the impact of this book of psalms has continued to this day, through multiple editions, denominations, and generations!

The 1933 hymnal of America’s “Northern Presbyterian Church” made generous use of the 1912 “Psalter” as a source for singing many of the Psalms. Both the “Trinity Hymnal” of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (1961) and the revised edition of 1990, in cooperation with the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA), contain many of the metrical Psalms from that 1912 “Psalter.” And that proposed URC “Psalter Hymnal” has now been completed in a joint effort by the URC and the OPC as the 2018 “Trinity Psalter Hymnal.” It contains all 150 Psalms, many of them from the 1912 “Psalter,” thus perpetuating the legacy and usefulness of that effort from more than a century ago.

The hymnal text of the metrical setting of this Psalm follows very closely the Hebrew original.

In stanza 1, we sing our request to be heard, since we belong to Him. It is very personal, addressing Him as Jehovah (His personal covenant name given to Israel), with the repeated use of the first person singular possessive pronoun, “my.” And it reflects the fact that the psalmist knows he will be heard because of the intimate connection to “my King, my God.” Even in the midst of opposition, there is the certainty that God will hear this prayer, offered up “as morning sacrifice.”

O Jehovah, hear my words, To my thoughts attentive be;

Hear my cry, my King, my God, I will make my prayer to Thee.

With the morning light, O Lord, Thou shalt hear my voice arise,

And expectant I will bring Prayer as morning sacrifice.

In stanza 2, we sing the basis of our hope: that God hates evil. It is here that we begin to note the theme of divine justice. This is a God whose eyes are too pure to even look on evil (Habakkuk 1:13). He loves righteousness and hates evil. But it’s not only evil; He hates evil doers. Here the evil are described as sinners, proud, lying, with violence, and deceit.

Thou, Jehovah, art a God Who delightest not in sin;

Evil shall not dwell with thee, Nor the proud Thy favor win.

Evil doers Thou dost hate, Lying tongues Thou wilt defeat;

God abhors the man who loves Violence and base deceit.

In stanza 3, we sing of our hope in the one who can deliver and lead us. This is not only a God of righteousness; He is also a God of grace. The right way for oppressed believers to respond is to flee immediately to the Lord, to bow “toward Thy holy place,” asking that He would “lead me in Thy righteousness,” keeping me from letting my feet turn aside.

In the fulness of Thy grace To Thy house I will repair;

Bowing toward Thy holy place, In Thy fear to worship there.

Lead me in Thy righteousness, Let my foes assail in vain;

Lest my feet be turned aside, Make Thy way before me plain.

In stanza 4, we sing these additional accusations that we bring against them, asking that God would judge them. They are “false and faithless,” “no truth is found” in their mouths, they speak “deadly words,” and in language reminiscent of Genesis 6:5, “All their thoughts with sin abound.” And so our desire is that God would bring “their plans to naught,” and “hold them guilty.” And we see clearly here that the issue is not that they have made themselves to be our enemies, but that they have set themselves against God as His enemies.

False and faithless are my foes, In their mouth no truth is found;

Deadly are the words they speak, All their thoughts with sin abound.

Bring, O God, their plans to naught, Hold them guilty in Thy sight,

For against Thee and Thy law They have set themselves to fight.

In stanza 5, we sing our confidence that the Lord will hear and answer. We can trust Him to do what is right in our cause, even if we do not see it now, or even in our lifetime. We can be joyful, knowing that we are “safely guarded,” compassed about by His favor “as a shield.” Here is one of the instances where we walk by faith in who He is and what He has promised, rather by sight in what we see or how we feel.

O let all that trust Thy care Ever glad and joyful be;

Let them joy who love Thy name, Safely guarded, Lord, by Thee.

For a blessing from Thy store To the righteous thou wilt yield;

Thou wilt compass him about With Thy favor as a shield.

The tune ABERYSTWYTH is the best-known of the roughly 400 hymn tunes composed by Joseph Parry (1841-1903). He was born into a poor but musical Welsh family in Glamorganshire, the seventh of eight children. Although he showed musical gifts at an early age, he was sent to work in the puddling furnaces of a steel mill at the age of 9, laboring at a 56 hour week. His family immigrated to a Welsh settlement in Danville, Pennsylvania in 1854 where he found a job in a local iron works, and where he later started a musical school. He served there as the organist for the Mahoning Presbyterian Church. Some of his coworkers in the iron works were musicians and offered him music lessons. While in Danville he married Jane Thomas. They had three sons and two daughters. He traveled around the United States and in Wales, performing, studying, and composing music, and he won several Eisteddfodau (singing competition) prizes.

Returning to England, he studied at the Royal Academy of Music and earned a doctorate at Cambridge where part of his tuition was paid by interested community people who were eager to encourage his talent. From 1873 to 1879 he was professor of music at the Welsh University College in the town of Aberystwyth. He established private schools of music in Aberystwyth and in Swansea, where he became the organist at Ebenezer Chapel. He was lecturer and professor of music at the University College of South Wales in Cardiff from 1888 until his death in 1903. He was a man of genuine devotion to the Lord.

A prolific composer, he produced oratorios, cantatas, an opera, orchestral and chamber music, as well as his 400 hymn tunes, many of which are found in hymnals today. The ABERYSTWYTH tune, first published in 1879, is recognized by many as the music with which we sing Wesley’s hymn, “Jesus, Lover of My Soul.” He died of the effects of blood poisoning after a second surgery. His last composition was written during his final illness, a tribute to his wife, Jane, titled, “Dear Wife.” At least 7,000 people attended his funeral, lining the route from his home to Christ Church. Ministers of several denominations assisted in the service. He was buried in the Saint Augustine’s Churchyard at Penarth. Shortly after his death, a national fund was established in his name to provide for his widow.

Here you can hear the singing of this Psalm.