What more wonderful theme could come from our lips than that of the love of God? It is there in the best-known verse in the entire Bible, John 3:16: “God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in Him should not perish but have everlasting life.” Not only believers in the devotional thoughts in the privacy of their homes and in their attitude in corporate worship as their hearts are warmed by this consideration, but also preachers and theologians in the depths and heights of their detailed examinations of this great theme are left in awe and wonder at its unsearchable limits. One of the greatest treatises in all the history of Christendom is Jonathan Edwards’ classic 18th century exposition of Paul’s words in “the love chapter,” in 1 Corinthians 13:1-8. In his sermon, “Heaven, A World of Love,” he demonstrates that heaven’s greatest joy will be that of experiencing eternally the ineffable love of God.

Another classic, only this time in our own day, is J. I. Packer’s “Knowing God.” In a series of chapters, he outlines what God has revealed about Himself in His Word, carefully examining another attribute in each chapter. The entire book thrills the soul every time we read it. Packer’s chapter on the love of God is one of the highest peaks within the entire mountain range of the divine attributes that Packer “unpacks.” He first writes that “‘God is love’ is not the complete truth about God so far as the Bible is concerned.” And then a few pages later he wrote that “‘God is love’ is the complete truth about God so far as the Christian is concerned.”

That distinction is very important, since liberals tend to focus on God’s love as if it was the only attribute. They treat it as something that virtually cancels out God’s justice, God’s jealousy, God’s wrath, and God’s punishing sin. Such an idea was at. The heart of Rob Bell’s 2011 book, “Love Wins.” That view has been so extreme that one denomination in their hymnal revision tried unsuccessfully to change a key phrase in the Getty/Townsend hymn, “In Christ Alone.” Instead of “And on the cross as Jesus died the wrath of God was satisfied,” they sought to replace it with, “And on the cross as Jesus died the love of God was magnified.” It certainly was magnified, but that attempt made clear that they did not believe in the wrath of God. No, God’s love is actually magnified most spectacularly by His satisfying His wrath on Christ in our place.

Returning to Packer’s “Knowing God,” here is the definition of God’s love that he offers, and then expounds phrase by phrase through the rest of the chapter. “God’s love is an exercise of His goodness towards individual sinners whereby, having identified Himself with their welfare, He has given His Son to be their Saviour, and now brings them to know and enjoy Him in a covenant relation.” And if we simply go to a concordance to find a fuller list of Scriptures that inform us about God’s love, we will have a marvelous adventure ahead of us to consider such texts as Romans 8:38-39 or Ephesians 3:17-19.

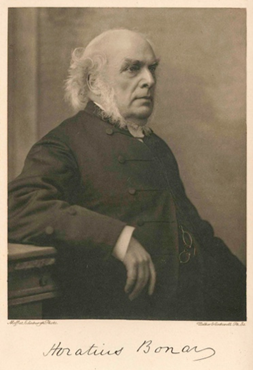

One of the great hymns about the love of God is Horatius Bonar’s magnificent Scottish hymn, “O Love of God, How Strong and True.” Horatius Bonar (1808-1889) was born in Edinburgh, educated in that city, and then ordained to pastoral ministry in 1837, serving first in Kelso. He was part of the evangelical exodus of the “Disruption” into the Free Church of Scotland in 1848. In 1866 he accepted a call to serve as pastor at the Chalmers Memorial Church, and in 1883 was chosen Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland.

He stood out in his generation as a champion of orthodoxy. He is best known today for his hymns, and has been called “The Prince of Scottish Hymn Writers.” Nearly 100 of his texts are in use in hymnals today across a wide span of denominations. They include “I Heard the Voice of Jesus Say,” “Blessing and Honor and Glory and Power,” “Here, O My Lord, I See Thee Face to Face,” “Not What My Hands Have Done,” “Thy Way, Not Mine, O Lord,” “A Few More Years Shall Roll,” and “I Lay My Sins on Jesus.” His hymns all reflect a very deep personal spirituality to be embrace by the singer(s). They are clear about the person and work of Jesus, focusing on His substitutionary atonement. Bonar had a special interest in prophecy and in the much-anticipated Second Advent of Christ.

One of his greatest compositions is the majestic song, “O Love of God, How Strong and True.” In the comments below about the text, it is evident that this has come from the heart of a man for whom his passion was this God of love. His poetic descriptions of that divine love are cast in extraordinarily eloquent language. When combined with the JERUSALEM tune by Parry, it rises to the level of glorious regal majesty, befitting the King of Love.

Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848-1918) is one of the most distinguished composers of the Victorian Anglican Church. He is remembered today, among other things, for the magnificent anthem based on Psalm 122, “I Was Glad,” written for the 1902 coronation of England’s King Edward VII. It continues to be a favorite in church choral repertoire, performed with two choirs, organ and brass. After his mother died and his father re-married, he and his two siblings were raised in a preparatory school. His musical interest was nurtured by the headmaster and two organists, and he soon became a skilled keyboardist.

During his study at Eton College, he developed heart trouble that would plague him for the rest of his life. He studied organ with George Elvey, organist of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, and eventually earned his music degree. He continued study in law and modern history at Exeter College, Oxford. At his father’s urging, he tried insurance work as an underwriter at Lloyd’s of London from 1870-1877, something he found very unsatisfying. In 1872 he married Elizabeth Maude Herbert and they had two daughters. He returned to music, studying piano, and began writing music again.

As his compositions began to come into public notice about 1875, he became an assistant editor for George Grove and his new “Dictionary of Music and Musicians,” contributing 123 articles to it himself. In 1883 he became professor of composition and musical history at the Royal College of Music and in 1895 succeeded Grove as head of the college. He also succeeded John Stainer (composer of “The Crucifixion”) as Professor of Music at Oxford (1900-1908). Though he had major academic responsibilities, he was able to continue to compose and orchestrate.

In 1895 Parry succeeded Grove as head of the college, remaining in the post for the remainder of his life. He also succeeded John Stainer as Heather Professor of Music at the University of Oxford (1900-1908). His academic duties were considerable and likely prevented him from composing any more than he did. Those who studied under Parry at the Royal College included Ralph Vaughn Williams, Gustav Holst, Frank Bridge, and John Ireland. Parry had the ability when teaching music to ascertain a student’s potential for creativity and direct it positively. Parry was also an avid sailor and owned several yachts, becoming a member of the Royal Yacht Squadron in 1908, the only composer so honored. He was a Darwinian and a humanist. His daughter reiterated his liberal, non-conventional thinking. On medical advice he resigned his Oxford appointment in 1908 and subsequently produced some of his best-known works. In 1918 he contracted Spanish flu during the global pandemic and died at Knightsscroft, Rustington, West Sussex. In 2015, unpublished works of Parry’s were found hidden away in a family archive. It is thought some may never have been performed in public. The documents were sold at auction for a large sum.

Parry’s JERUSALEM tune was joined with Bonar’s text and is sung often in churches today. It was sung in Washington Cathedral in 2004 for the funeral of President Ronald Reagan. The music is recognizable today to many from its having been included near the end of the movie, “Chariots of Fire,” about 20th century olympic runner and missionary martyr, Eric Liddell. Parry’s JERUSALEM tune has also become something of an unofficial British national anthem with the text from William Blake’s odd poem, “And Did Those Feet in Ancient Times,” from the preface to his epic “Milton, a Poem in Two Books.” It has become England’s most popular patriotic song. The song has also had a large cultural impact in Great Britain. It is sung every year by an audience of thousands at the end of the last night of the proms in the Royal Albert Hall and simultaneously in the “Proms in the Park” venues throughout the country.

It is often assumed that Blake’s 1804 poem was inspired by the apocryphal story that a young Jesus, accompanied by Joseph of Arimathea, a tin merchant, travelled to what is now England, and visited Glastonbury during His unknown years. Most scholars reject the historical authenticity of this story out of hand, and according to British folklore scholar A. W. Smith, “there was little reason to believe that an oral tradition concerning a visit made by Jesus to Britain existed before the early part of the twentieth century.” Blake does not name the walker on “England’s green and pleasant land.” According to a story available at the time of Blake’s writing, in Milton’s “History of Britain,” Joseph of Arimathea, alone, travelled after the death of Jesus, and first preached to the ancient Britons. The poem’s theme is linked to Revelation 3:12 and 21:2, describing a Second Coming, in which Jesus establishes a New Jerusalem, a metaphor for Heaven, a place of universal love and peace.

And did those feet in ancient time, Walk upon England’s mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God, On England’s pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine, Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here, Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my Bow of burning gold: Bring me my Arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold: Bring me my Chariot of Fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem, In England’s green & pleasant Land.

In the most common interpretation of the poem, Blake asks whether a visit by Jesus briefly created heaven in England, in contrast to the “dark Satanic Mills” of the Industrial Revolution. Blake’s poem asks four questions rather than asserting the historical truth of Christ’s visit. The second verse is interpreted as an exhortation to create an ideal society in England, whether or not there was a divine visit. This mythical patriotic text is hardly something that deserves a place in Christian worship. Perhaps the closest it comes is in the phrase about “chariots of fire,” which resembles the account of Elijah being taken into heaven in 2 Kings 2:11.

Returning to Bonar’s hymn text, we have these magnificent lines about the love of God.

Stanza 1 presents an awesome collection of more than a dozen of the excellencies of God’s love. Each one warrants careful examination on its own. Many are immediately obvious in their meaning. But several are unexpected, like “uncomprehended and unbought.” Such love is more than we can fully comprehend, and it is so grace-based and unmerited that we could do nothing to buy it. The phrase “far deeper than man’s deepest hate” is stunning, when we realize just how deep man’s hate is as we hear of wicked atrocities in the news. And what an unusual description in the final line that flows out of God’s aseity, His complete independence, drawing His being and nature from nothing outside of Himself: His love is “self-fed, self kindled” like the light.

O love of God, how strong and true, eternal and yet ever new,

uncomprehended and unbought, beyond all knowledge and all thought!

O love of God, how deep and great, far deeper than man’s deepest hate;

self-fed, self-kindled like the light, changeless, eternal, infinite.

Stanza 2 takes those attributes and applies them to our hearts for our times of pain and suffering. His love is most precious to us when we most need it, “in days of weariness and ill, in nights of pain and helplessness,” when His “wide-embracing, wondrous love” is poured out in our hearts and minds “to heal, to comfort, and to bless!” And this love is so wide, that we see it not only in our hearts, but also in the world around us as He lovingly cares for His creation, “in the sky above,” “in the earth below,” and in seas “that swell and streams that flow.”

O heav’nly love, how precious still, in days of weariness and ill,

in nights of pain and helplessness, to heal, to comfort, and to bless!

O wide-embracing, wondrous love! We read you in the sky above,

we read you in the earth below, in seas that swell and streams that flow.

Stanza 3 moves to the greatest demonstration of God’s love, far greater than just helping us through our physical and emotional trials, and far greater than His care for the sky, the earth, and the seas. The best place to “read” of His love is at Calvary where He “came bearing for us the cross of shame.” It was there, as He who knew no sin became sin for us (2 Corinthians 5:21), that we might receive that gift of eternal life. And in the final lines of the hymn, we read His power best in this work of redemption by which He has rescued us from “the darkness of the grave” which He endured in our place, securing for us that “resurrection light” in which He became “the first fruits from the dead” (1 Corinthians 15).

We read you best in Him who came bearing for us the cross of shame;

sent by the Father from on high, our life to live, our death to die.

We read your pow’r to bless and save, e’en in the darkness of the grave;

still more in resurrection light we read the fullness of your might.

Stanza 4 becomes pure praise, exalting this God of such incredible love. His love has been there for us “through all the perils of our way.” This love enables us to “rest, forever safe, forever blest.” And so we will “ever praise Your name,” and “evermore Your praise proclaim.” The more we consider Bonar’s lyrics, the more we may come to feel that this is one of the most glorious texts in our hymnals.

O love of God, our shield and stay through all the perils of our way!

Eternal love, in you we rest, forever safe, forever blest.

We will exalt You, God and King, and we will ever praise Your name;

we will extol You ev’ry day, and evermore Your praise proclaim.

Here is this majestic hymn as sung at the funeral of President Ronald Reagan in 2004.