Do you know what is the oldest text in our Bibles? Some would think of Psalm 90, “Lord, You have been our dwelling place in all generations … a thousand years in Your sight are but as yesterday when it is past.” Moses wrote that in the 14th century BC. Even older than that would be Job, since his life seems to have been lived about the time of Abraham, closer to 1800 BC.

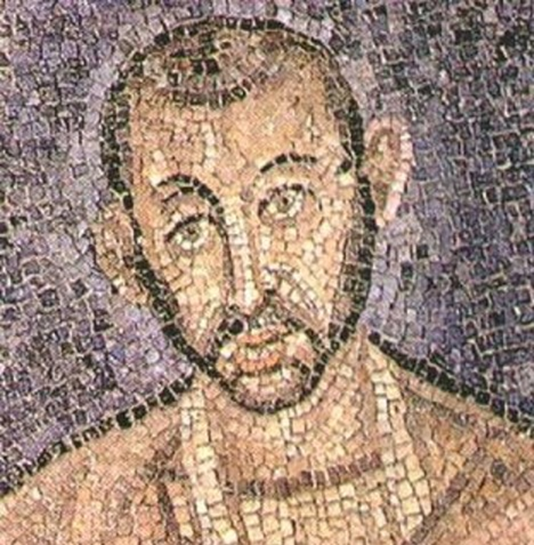

How about the oldest hymn that we sing today? One possibility would be the modern versions of the 4th century “Te Deum.” We find it in most hymnals with the text “Holy God, We Praise Thy Name.” It was an early creed, not really a poem. But when considering poetry adapted to singing that would probably be “Of the Father’s Love Begotten,” written in Latin by Marcus Aurelius Clemens Prudentius, who lived from 348 to 413 AD. That would make him a contemporary of Augustine of Hippo (354 to 430 AD), the greatest theologian before the Reformation. Of course, today we sing an English translation of that ancient poetic text.

“Of the Father’s Love Begotten” is a magnificent hymn, most often sung as part of the church’s repertoire for Advent. Its original Latin title was “Corde natus ex parentis ante mundi exordium,” literally “Born from the parent’s heart before the beginning of worlds.” Marcus Aurelius Clemens Prudentius was a Spanish poet from Saragossa in northern Spain, a very important city in the Roman Empire. Coming from a prominent family, he left military life to become a successful lawyer and a powerful judge, finishing his career as a court official for the Christian Emperor Theodosius.

After he was converted, he made it his life’s ambition to bring the gospel to his colleagues in the law profession. He did not begin writing poetry until the age of 57, when he grew weary of civic life, considering his life thus far to have been a waste. For the last decade of his life he retired to write hymns and poetry, writing some of the most beautiful hymns of his day. He penned this ode as part of a larger collection of poetry, “Liber Cathemerinon,” consisting of twelve long poems, one for each hour of the day.

This hymn was not translated into English until the mid-nineteenth century. The first translation was given by John Mason Neale (1818–66) and was included in Hymnal Noted of 1851. The second and separate translation was done by Henry W. Baker (1821–77) and was inserted in the original 1861 edition of Hymns Ancient & Modern. By the time this hymn comes to us in our hymnal, it has traveled an amazing journey through 17 centuries and at least four countries: a Latin poem from a Catholic Spanish poet in the fourth century, a tune from Italy in the 11th century, a translation from an Anglican in 19th-century England and a harmonization in the 20th century by an American Episcopal musician. The original had nine stanzas plus the refrain, “Evermore and evermore.” A later doxology that was added probably came from the closing words of the complete poem.

It seems likely that Prudentius wrote this text to combat one of the most dangerous and prominent heresies of the ancient church. The teachings of Arius (250-336), bishop of Alexandria, had been spreading rapidly. There were even songs circulating that promoted his erroneous ideas. At the Council of Laodicea in 367, the Roman Church over-reacted by banning all congregational singing, permitting songs in worship only by clergy and in monasteries. This was not overcome until the time of the Reformation. Martin Luther’s hymns restored congregational song to the people after being prohibited for a thousand years!

Arius taught that God the Son had not co-existed throughout eternity. There was a time when the Son was not. Arius taught that the Son was a created being, that occurring sometime before His incarnation, and therefore was not equal to the Father. In this view Jesus was viewed as more than man but less than God. Obviously, that strikes at the very heart of the gospel. This heresy was addressed by the Council of Nicaea in 325 and by the Council of Constantinople 381. It was at the first of these that “The Nicene Creed” was developed to clearly establish the eternity and deity of the Son. We benefit from those deliberations today, in part, as we use “The Nicene Creed.”

Since the hymn was first written in Latin, it is not surprising that there are multiple translations and settings of the hymn. Here is an English translation and metrical setting of the original nine stanzas that came from Prudentius’ pen, and from his heart. There is a wonderful progression in the stanzas as they tell the story of redemption. Stanza one speaks of the Son’s eternal nature. Stanza two is about creation. Stanza three chronicles the fall. Stanza four moves into redemption with the virgin birth. Stanza five links the Christ child to ancient prophecies. Stanza six is a chorus of praise to the Messiah. Stanza seven warns of final judgment for the wicked. Stanza eight tells of men, women, and children singing their songs of praise. And Stanza nine concludes the hymn with a song of victory to Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Most Christians will recognize some of the verses, but sadly not all.

Stanza 1 describes the Son’s eternal divine nature. There was never a time when He did not exist. He is the alpha and the omega, the one who has always been, from before the beginning into the far distant future. He is of the same divine nature as the Father, drawing His being (“begotten”) from the Father, but not as one created by the Father. All things exist because of Him (John 1).

Of the Father’s love begotten,

Ere the worlds began to be,

He is Alpha and Omega,

He the source, the ending He,

Of the things that are, that have been,

And that future years shall see,

Evermore and evermore!

Stanza 2 describes the Son as pre-dating creation. His existence knows no beginning point. He is the one through whom the Father created all that exists (John 1). It was His voice that spoke light and life, skies and oceans, trees and grains, cattle and birds, stars and moons into existence. The one who is “the Word” created all things by His spoken word.

At His Word the worlds were framèd;

He commanded; it was done:

Heaven and earth and depths of ocean

In their threefold order one;

All that grows beneath the shining

Of the moon and burning sun,

Evermore and evermore!

Stanza 3 describes the Son coming to rescue sinful human beings. Adam’s sin brought the human race and all creation under the curse in the fall. That is why there is sadness and disease and death. The Son has come “in human fashion” to suffer in our place. As a result of that, we are no longer “doomed to endless woe,” but can be delivered from the “dreadful gulf” in hell.

He is found in human fashion,

Death and sorrow here to know,

That the race of Adam’s children

Doomed by law to endless woe,

May not henceforth die and perish

In the dreadful gulf below,

Evermore and evermore!

Stanza 4 describes the Son coming to be born miraculously of a virgin, conceived in her womb by the Holy Spirit. Here we see the deity of the Spirit along with the Father and the Son, further challenging the Arian heresy. Here the Savior is named as Redeemer, even as an infant when His “sacred face” was “first revealed” to mankind..

O that birth forever blessed,

When the virgin, full of grace,

By the Holy Ghost conceiving,

Bare the Saviour of our race;

And the Babe, the world’s Redeemer,

First revealed His sacred face,

evermore and evermore!

Stanza 5 describes the Son coming to fulfill ancient prophecy. Each advent season, we are treated to a rehearsal of the prophecies of the Messiah who has now come, from the first promise in the garden in Genesis 3:15 to the gospel predictions in Isaiah and even the naming of his birthplace, little Bethlehem, in Micah 5:2.

This is He Whom seers in old time

Chanted of with one accord;

Whom the voices of the prophets

Promised in their faithful word;

Now He shines, the long expected,

Let creation praise its Lord,

Evermore and evermore!

Stanza 6 describes the praise sung to the Son by heaven’s angelic hosts. It takes the form of a call to worship extended to the angelic hosts of heaven and to those on earth who join their voices with them. It is also a prophecy of the time to come when all “powers” and “dominions” will bend the knee, confessing that Jesus is Lord (Philippians 2),

O ye heights of heaven adore Him;

Angel hosts, His praises sing;

Powers, dominions, bow before Him,

and extol our God and King!

Let no tongue on earth be silent,

Every voice in concert sing,

Evermore and evermore!

Stanza 7 describes the judgment of those who refuse to honor the Son. This Savior is also a judge who will deal righteously with those “departed souls” who have lived as rebels and who will face fierce vengeance before the King. It will impossible for them to strive against His hand as they will be driven from His face forever.

Righteous judge of souls departed,

Righteous King of them that live,

On the Father’s throne exalted

None in might with Thee may strive;

Who at last in vengeance coming

Sinners from Thy face shalt drive,

Evermore and evermore!

Stanza 8 describes the singing of human worshippers that is directed to the Son. The words reach out to encompass both old and young, men and boys, “matrons, virgins, and little maidens.” What a sight and sound that will be when all those redeemed voices are joined together in glad song. In that day not only will our hearts be pure and perfect, but so also will be our music.

Thee let old men, thee let young men,

Thee let boys in chorus sing;

Matrons, virgins, little maidens,

With glad voices answering:

Let their guileless songs re-echo,

And the heart its music bring,

Evermore and evermore!

Stanza 9 describes the praise given to the Son, along with the Father and the Spirit, in a concluding doxology to the triune God. This is the song that will never grow old, attributing “honor, glory, and dominion” to this Lord, along with “eternal victory.” How fitting that each stanza ends with the same theme as we find in this paean of praise: “evermore and evermore.” As Prudentius is there now, so will we join him and all who have gone before us, singing words like these, like those we see recorded in the vision of the heavenly throne room in Revelation 4 and 5. Until we are there, may songs like this prepare our hearts for such worship.

Christ, to Thee with God the Father,

And, O Holy Ghost, to Thee,

Hymn and chant with high thanksgiving,

And unwearied praises be:

Honour, glory, and dominion,

And eternal victory,

Evermore and evermore!

This hymn was not sung to the famous tune DIVINUM MYSTERIUM originally. That melody comes from the 11th century and was used with a different text. The harmonization of the melody comes from The Hymnal 1940 in an arrangement by C. Winfred Douglas, who was the musical editor of that Episcopal hymnal. It is based on a plainsong chant from the 13th century and it is profound in its simplicity. It is filled with stepwise motion that naturally moves up and down the tessitura of the voice and helps to capture the sense of the biblical mystery of the incarnation.

Here is a performance of an anthem based on the hymn. It comes from a Christmas concert with choir and orchestra from Augustana College.

And here is a video of the song as performed in England’s Ely Cathedral in an arrangement by the late Sir David Willcocks. In this, he has set the melody in the original pattern of triplets, rather than the plainsong rendering of flowing eighth notes.