The Gospel accounts of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on what we now call Palm Sunday stir our imaginations with the descriptions of the excitement of the crowd. What a thrill it must have been as people rose on that morning, just days before the annual Passover celebrations. Jesus’ public ministry had been attracting more and more attention during the past 18 months, as He turned His focus increasingly from Galilee toward Jerusalem. Not only were the stories spreading everywhere about His teaching and His miracles. By this time there would have been increasing numbers of eyewitnesses from Galilee who would have come to Jerusalem, telling what they had seen and heard.

Now it was also a matter of what so many must have been hoping: that Jesus would turn out to be the long-awaited Messiah. For centuries, the prophecy in Zechariah 9:9 had been pointing to the Messianic king who would come, riding on a donkey. Passion s must have exploded when word spread through the streets that morning, that not only was Jesus in town, but that He had been spotted approaching the city riding on a donkey. As He entered, the crowds threw down their clothes to make a royal pathway for Him, waving palm branches as they sang, “Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord” (Psalm 118:26). Clearly, they recognized the Messianic implications of this connection. And we must realize that it was no coincidence that Jesus chose to come this way. He knew the prophecy as well, and made a conscious decision to fulfill it, publicly claiming to be the Messianic King. We can appreciate something of the people’s excitement as we struggle with the advance of anti-Christian legislation and increased religious departure from biblical fidelity. Just think of how exciting it would be for us today if we heard of the approach of one who could turn things around for us!

Sometimes it has been suggested that one of the tragedies of the passion narrative is the way the crowd turned against Jesus so quickly, hailing Him as Messiah on Sunday and then calling for His crucifixion just five days later. While that may be an accurate description of what happened, there is another and more likely explanation. We are not strangers to the sad dynamic of someone claiming to have come to Christ with joy, and later turning away in rejection or disinterest. Jesus predicted exactly that in His Parable of the Soils in Matthew 13. But in this case of passion week there is a more probable explanation in the deception and manipulation of the religious establishment, and especially the High Priest with the Sanhedrin, in their determination to have Jesus killed. They, and their supporters, were probably the ones who had been contacted to arrive at this illegal early morning assembly and shout for Jesus’ crucifixion.

In addition to the Gospel narratives of Jesus’ triumphal entry, Psalm 24 has rightly become a text for use in our Palm Sunday worship each year. Many of us can remember processing into the sanctuary that day, perhaps as part of the children’s choir, each holding a large palm branch. And then we would all join in the responsive reading of Psalm 24. “Lift up your heads, O gates! And be lifted up, O ancient doors, that the King of glory may come in. Who is this King of glory? The LORD, strong and mighty, the LORD, mighty in battle!” That was fulfilled on that Palm Sunday. But won’t it be marvelous when it is fulfilled in a far greater sense when this King of glory returns in His second coming, entering the gates of creation, as it were, ushering in the full revelation of His kingdom and His kingship?

Understandably, the two sections of our hymnals that have the greatest number of songs for our congregational song are those associated with Jesus’ birth (Advent and Christmas) and Jesus’ death (from Palm Sunday to Easter). Check out the table of contents of your church’s hymnal to see if that’s true. Then look through them to see how many of them you know, and how many of them are sung in your church. This is a rich treasury of biblical truth that remains significantly untapped in many places.

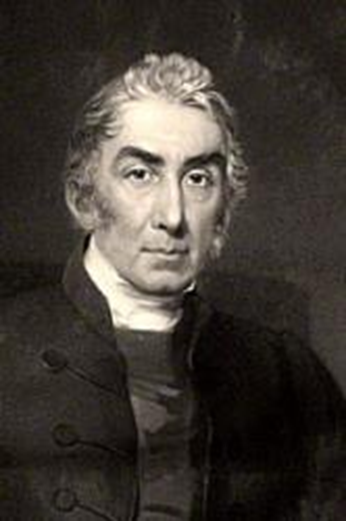

Among the festive hymns for Palm Sunday is Ride On, Ride On in Majesty, a very fitting composition to celebrate this public acknowledgement of Jesus’ royal deity and this major event in His fulfillment of prophecy leading up to Calvary. It was written in 1820 by Henry Hart Milman (1791-1868) and began to appear in hymnals starting with Reginald Heber’s hymn collection in 1827, before Heber became Bishop of Calcutta. There are 13 of his hymns in Heber’s hymnal, along with Heber’s own classic, Holy, Holy, Holy. According to John Julian’s “Dictionary of Hymnology,” by 1907 Ride On, Ride On in Majesty had become the most popular English language hymn for Palm Sunday. It continues to be so, and is often sung as a processional hymn on that day.

Milman was the youngest son of a baronet who had been given the title as a court physician to George III. He was educated at Eton and Oxford, where his career was nothing short of brilliant as he took first place honors in classics. He was ordained in 1816, and two years later became parish priest of St Mary’s, Reading. In 1821 he was elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford (this was a part-time position requiring three lectures a year). In 1830 he published his History of the Jews, which brought down on him the censure of the Church. It treats the Jews as an Oriental tribe, and all miracles are either eliminated or evaded. He was among the first of those in England who imbibed the liberalism of German scholarship in biblical interpretation, trying to interpret the Bible apart from the supernatural, as just another piece of ancient religious literature. Despite this, Sir Robert Peel made him Rector of St. Margaret’s, Westminster in 1835, and in 1849 he became Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral.

There have been several tunes used for the text over the years, including WINCHESTER NEW, TRURO, and KING’S MAJESTY. An alternative tune (in the “Trinity Hymnal)” is ST DROSTANE by John Bacchus Dykes, who composed a large number of hymns in common use today, including those to which we sing Holy, Holy, Holy; The King of Love My Shepherd Is; O Come and Mourn with Me Awhile; I Heard the Voice of Jesus Say; Come, Holy Spirit, Heavenly Dove; Christian, Dost Thou See Them; and Eternal Father, Strong to Save. There are striking similarities between ST DROSTANE and WINCHESTER NEW, the latter originally appearing in Hamburg in 1690 from George Neumark and then later adapted by Johann Freylinghausen in 1704, but with minor rhythmic variations. St. Drostan (it seems to be spelled without the final ‘e’) was a follower or possibly nephew of St. Columba and sailed with him from Ireland to Scotland in about AD 585. He founded a monastery at Old Deer in Aberdeenshire, but no trace remains.

An interesting feature of the hymn in its literary structure is the fact that each stanza begins with the same words, Ride on! ride on in majesty! This is a command, but who is speaking, and to whom are they addressing this charge? It’s pretty clear that the words are addressed to Jesus, calling on Him to continue moving forward as He rides into the city toward Calvary. But who is calling Him to do so? Is it the crowd in the streets? Is it angels and saints looking down from heaven’s courts? Or is it us, who join with those present that day, adding our voices to theirs? However we answer that question, we praise God that Jesus did indeed ride on, all the way to Calvary, to secure our salvation.

In stanza 1, the scene is set: Jesus riding on a donkey, though His royal state would have suggested a white horse as more appropriate. But in fulfilment of the prophecy, His steed is one that points us immediately to His humility. All the tribes cry “Hosanna,” the exclamation from Psalm 118, as the hymn goes on to picture the sight of waving palm branches and clothing carpeting the road before Him.

Ride on! ride on in majesty! Hark! All the tribes Hosanna cry;

O Savior meek, pursue Thy road With palms and scattered garments strowed.

In stanza 2, the humiliation Paul described in Philippians 2 is presented in a further contrast: though He rides in majesty, yet He rides in lowly pomp. We know He will triumph over death and sin, but only by suffering the pain and curse of death for Himself.

Ride on! ride on in majesty! In lowly pomp ride on to die:

O Christ, Thy triumphs now begin O’er captive death and conquered sin.

In stanza 3, we are lifted up to view the scene from a higher vantage point, that of the balcony of heaven. There “winged squadrons” of angels in the sky look down on the sight. The one whom they have worshiped from the first days of their creation, the one before whom they bowed in celestial courts, that same one must at this point have been a puzzlement to them as they “look down with sad and wondering eyes to see th’approaching sacrifice.”

Ride on! ride on in majesty! The winged squadrons of the sky

Look down with sad and wondering eyes To see th’approaching sacrifice.

In stanza 4, it’s the Father’s perspective that we consider. There is a sense of nearness as the “last and fiercest strife” is almost at hand, as if Jesus is being encouraged to press on; that the end is almost in sight. And “the Father on His sapphire throne” is watching with approval, looking forward to the completion of the mission and anticipating the triumphant return to heaven of “His own anointed Son.”

Ride on! ride on in majesty! Thy last and fiercest strife is nigh;

The Father on His sapphire throne Expects His own anointed Son.

In stanza 5, we are returned to the immediate scene. The crowds are cheering now, but within days the Son will be raised up on the cursed cross (Galatians 3:13). There has been the pomp of majesty, but before Jesus can claim His “power and reign,” it will be transformed in His death as He must “bow Thy meek head to mortal pain.” And that’s what has made it possible for our heads to be lifted high in victory through His atonement.

Ride on! ride on in majesty! In lowly pomp ride on to die:

Bow Thy meek head to mortal pain, Then take, O God, Thy power and reign.

Here is a recording of the hymn to the ST DROSTANE tune, as sung by the congregation of Pittsburgh’s East Liberty Presbyterian Church.