Of all the Christ-centered events in the biblical account of Jesus’ life, probably the one least celebrated in the Church Year is that of His ascension. The details of the event are clearly described in Scripture as the concluding step in His earthly ministry, and also as the culmination of that work of redemption in His heavenly ministry. We find it in the Gospels, in Acts, and in the epistles. It is especially prominent in the book of Hebrews as the author relates it to Jesus’ coronation and continuing intercession for us, as a Savior, who in Herman Bavinck’s words, has much remaining to do for the kingdom.

In 2015, the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals published an excellent essay by Pastor Tim Bertolet about the ascension in Hebrews. In it, he wrote this.

Hebrews is concerned with the climax of God’s revelation of himself in the person of the Son. Now in completion of the Old Testament revelations to the prophets, God has spoken in His Son. It is the climax of salvation history. In verse 3b-4, the main clause is “he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high.” This heavenly session of reign and rule would have been impossible without His death (3b) and by extension his resurrection (7:16b). Yet Hebrews draws attention to the reality of the ascension as the element of climax to the ‘it is finished’ of the cross.

Second, Hebrews itself tells us that the central focus of the book is the work of Christ in His heavenly ascension and session on our behalf. Hebrews 8:1 “Now the point in what we are saying is this: we have such a high priest, one who is seated at the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in heaven, 2 a minister in the holy places, in the true tent that the Lord set up, not man.”

We cannot make sense of the work of Christ if in the completion of the cross and resurrection he has not ascended bodily to heaven where He continues as both king and priest. The ascension of the Lord Jesus Christ is a part of the one event complex that brings God’s redemption to fulfillment.

Thus, the ascension of the Lord Jesus Christ draws the kingship of Christ into focus as the eternal Son is coronated as the true human king reigning over all of the Father’s creation. This is seen plainly in Hebrews as Christ’s ascension and sitting into heaven. Jesus is like a king who having conquered sits down to rule his kingdom, all creation. Just as He is king, He also ascends to take his seat as priest, ascended to minister in a new eschatological perfection of a glorified human state ….

In light of these considerations, we return to our opening question: what role, if any, does the ascension of Christ in the devotional and worship life of the believer? We would argue, along with the whole of Scripture that the ascension of Jesus Christ is an essential element of the redemption work of Christ. The Messiah who does not ascend bodily into heaven is no true Messiah. If we might riff from Pauline theology on the resurrection, without the historical ascension our faith and our preaching is in vain, we are still in our sins.

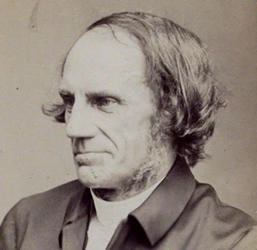

One of the most compelling hymns about the Ascension, “See the Conqueror Mounts in Triumph” was written by Christopher Wordsworth, D.D. (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln (1869-1885). Between 1830 and 1836 he was a fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge, where his career was an extraordinarily brilliant one. He was engaged as classical lecturer in the college for some time, and in 1836 was chosen Public Orator for the University. In the same year he was elected Head Master of Harrow School, and in 1838 he married Susan Hatley Freere. He became the most celebrated Greek scholar of his day. In 1869 he was elevated to the bishopric of Lincoln, which he held for more than fifteen years, resigning it a few months before his death, which took place on March 20th, 1885. As bearing upon his poetical character, it may be noted that he was the nephew of the famous poet-laureate, William Wordsworth, whom he constantly visited at Rydal up to the time of the poet’s death in 1850, and with whom he kept up a regular and lengthy correspondence.

This hymn was first published in his work, “The Holy Year” (1862), where it was a long hymn of 10 stanzas in the author’s favored 15.15.15.15 meter. It was originally intended for both Ascension Day and Pentecost, and was subsequently divided to give two separate hymns, five stanzas for Ascension and four, beginning “Holy Ghost, illuminator” for Pentecost, with a doxology to either part. Wordsworth explained his choice of meter based on its being an ancient rhythmical principle that the tetrameter trochaic of fifteen syllables should be specially employed on occasions where there is a sudden burst of feeling, after a patient waiting, or a continuous struggle.

In his classic 1892 “A Dictionary of Hymnology” John Julian judged that this hymn was “one of Bishop Wordsworth’s finest compositions, and is the nearest approach in style and treatment to a Greek ode known to us in the English language.” He further observed: “Prophecy, types, historical facts, doctrinal teaching, ecstatic praise, all are here.”

While Christopher Wordsworth was a very voluminous writer, the only one which claims notice from the hymnologist’s point of view is “The Holy Year,” which contains hymns, not only for every season of the Church’s year, but also for every phase of that season, as indicated in the “Book of Common Prayer.” Dr. Wordsworth, like the Wesleys, looked upon hymns as a valuable means of stamping permanently upon the memory the great doctrines of the Christian Church. He held it to be “the first duty of a hymn-writer to teach sound doctrine, and thus to save souls.” He thought that the materials for English Church hymns should be sought (1) in the Holy Scriptures, (2) in the writings of Christian Antiquity, and (3) in the Poetry of the Ancient Church. Hence he imposed upon himself the strictest limitations in his own compositions. He did not select a subject which seemed to him most adapted for poetical treatment, but felt himself bound to treat impartially every subject and branch of a subject that is brought before us in the Church’s services, whether of a poetical nature or not.

While Wordsworth wrote 10 stanzas, it would be hard to find a hymnal today that includes all of them. In most hymnals today, only stanzas 1, 2, and 5 are included. Here is the original text.

Stanza 1 sets the stage for the hymn by helping us to imagine the scene of the victorious Christ’s arrival into heaven. Like John in Revelation, it is as if we have been transported to the heavenly places ourselves to witness this joyful occasion and celebrate with the angels (Revelation 5:9-14).

See the Conqueror mounts in triumph, see the King in royal state,

Riding on the clouds His chariot, to His heavenly Palace gate;

Hark, the quires of angel voices joyful Hallelujahs sing,

And the portals high are lifted, to receive their heavenly King.

Stanza 2 continues the scene, starting with the rhetorical question drawn from Psalm 24, “Who is this that comes in glory?” The question is quickly answered by the proclamation of who Christ is. He is the God of armies, the Word who took on flesh and conquered His foes by His death and resurrection (John 1:14; Colossians 2:15).

Who is this that comes in glory, with the trump of jubilee?

Lord of battles, God of armies, He has gain’d the victory;

He who on the Cross did suffer. He who from the grave arose,

He has vanquish’d Sin and Satan, He by death has spoil’d His foes.

Stanza 3 looks back in time to the day of Jesus’ ascension with “raised hands in blessing,” leaving His friends to carry on the work of the Great Commission. “While their eager eyes behold Him, He upon the clouds ascends,” just as Luke described it in Acts 1. And in language that sounds like homesickness remedied, Jesus who from eternity had been with the Father, then returned “to His everlasting home.”

While He raised His hands in blessing, He was parted from His friends;

While their eager eyes behold Him, He upon the clouds ascends;

He who walk’d with God, and pleased Him, preaching truth and doom to come.

He, our Enoch, is translated to His everlasting home.

Stanza 4 has Bishop Wordsworth doing a masterful job of weaving together the themes of Christ as priest, king, and prophet with the types of Christ found throughout the Old Testament. In the resurrected and ascended Christ, we find the fulfillment of everything to which the prophets pointed (Luke 24:25-27). The language of typology connects Jesus with Aaron, Joshua, and Elijah, but doing far more than any of them had accomplished.

Now our heavenly Aaron enters, with His blood, within the veil;

Joshua now is come to Canaan, and the kings before Him quail;

Now He plants the tribes of Israel in their promised resting-place;

Now our Great Elijah offers double portion of His grace.

Stanza 5 tells how those of us who have been baptized into Christ have been united with Him in a resurrection like His (Romans 6:3-5). Being made alive together with Christ, God has raised us up and seated us with Him in the heavenly places (Ephesians 2:4-7) where He is adored. There we will reign as heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ (Romans 8:16-17).

Thou hast rais’d our human nature on the clouds to God’s right hand,

There we sit in heavenly places, there with Thee in glory stand;

Jesus reigns, ador’d by Angels; Man with God is on the Throne;

Mighty Lord, in Thine Ascension we by faith behold our own.

It is at this point that some hymnals have divided the hymn, with these first five stanzas sung for Ascension and the remaining stanzas in a separate hymn sung for Pentecost, as the focus turns initially to the Holy Spirit, before returning to details of the Ascension and then to a Gloria Patri.

Stanza 6 makes a dramatic connection between Stephen’s martyrdom and the ascended Savior, who that apostolic deacon apparently saw beckoning him home in those last moments before he died. In the hymn, we pray that our eyes might “look up with Stephen” to see the same Savior who is today “standing at God’s right hand,” preparing to call us home.

Holy Ghost, Illuminator, shed Thy beams upon our eyes,

Help us to look up with Stephen, and to see beyond the skies,

Where the Son of Man in glory standing is at God’s right hand,

Beckoning on His Martyr army, succouring His faithful band.

Stanza 7 calls us to remember that Jesus is not only preparing to call us home. He has gone before us, not to wait in passive inaction until that day arrives. He is preparing us for those heavenly mansions through the Spirit’s sanctifying work each day, and through all these days “pleading for us with prevailing prayer,” interceding for us before the throne (Hebrews 7:25). And at the same time, He is preparing for His future role of “summoning the world to Judgment on the clouds” when He will come again.

See Him, Who is gone before us, heavenly mansions to prepare,

See Him, Who is ever pleading for us with prevailing prayer;

See Him, Who with sound of trumpet and with His angelic train

Summoning the world to Judgment on the clouds will come again.

Stanza 8 anticipates that wonderful day, when our earthly struggles will have come to an end, and He will then “lift us up from earth to heaven; give us wings of faith and love.” What is it about that future that awaits us that should cause us the greatest joy in anticipation of our hour when His voice lifts us to glory? It won’t be anything less than the thrill of seeing Him whom our souls love, sitting “enthroned in glory in His heavenly Citadel.”

Lift us up from earth to heaven; give us wings of faith and love,

Gales of holy aspirations wafting us to realms above;

That with hearts and minds uplifted we with Christ our Lord may dwell,

Where He sits enthron’d in glory in His heavenly Citadel.

Stanza 9 entices us to long for that day of His appearing, when if not during our earthly lifetime, then as “we from out our graves may spring,” with the eagle’s wings of Isaiah 40:31, “flocking round our heavenly King, caught up on the clouds of heaven” we will “meet Him in the air, rise to realms where He is reigning, and may reign forever there.” This reminds us that His physical ascension guarantees our physical ascension.

So at last, when He appeareth, we from out our graves may spring,

With our youth renew’d like eagles, flocking round our heavenly King,

Caught up on the clouds of heaven, and may meet Him in the air,

Rise to realms where He is reigning, and may reign for ever there.

Stanza 10, in typical British fashion, brings the story to a conclusion with a Gloria Patri, giving glory to the Holy Trinity, “One God in Persons Three,” who, in perfect unity, brought about our salvation. How gladly we sing, “Glory both in earth and heaven, glory, endless glory be!”

Glory be to God the Father, Glory be to God the Son,

Dying, ris’n, ascending for us, Who the heavenly realm has won;

Glory to the Holy Spirit; to One God in Persons Three,

Glory both in earth and heaven, glory, endless glory be!

The tune RUSTINGTON was written in 1897 by one of the great names in British music, Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848-1918). He was born at Richmond Hill, Bournemouth, England, son of a wealthy director of the East India Company (also a painter, piano and horn musician, and art collector). His mother died of tuberciulosis shortly after his birth. His father remarried when he was three, and his stepmotherfavored her own children over her stepchildren, so he and two siblings were sometimes left out.

He attended a preparatory school in Malvern, then at Twyford in Hampshire. He studied music from 1856-58 and became a pianist and composer. His musical interest was encouraged by the headmaster and by two organists. He gained an enduring love for Bach’s music from Samuel Wesley and took piano and harmony lessons from Edward Brind, who also took him to the Three Choirs Festival in Hereford in 1861, where Mendelssohn, Mozart, Handel, and Beethoven works were performed. That left a great impression on the teenage Hubert. It also sparked the beginning of a lifelong association with the festival.

That year, his brother was disgraced at Oxford for drug and alcohol use, and his sister, Lucy, died of tuberculosis, as well. Both events saddened Hubert. However, he began study at Eton College and distinguished himself at both sport and music. He also began having heart trouble, that would plague him the rest of his life. Eton was not known for its music program, and although some others had interest in music, there were no teachers there that could help Hubert much. He turned to George Elvey, organist of St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, and started studying with him in 1863. Hubert eventually wrote some anthems for the choir of St George’s Chapel, and eventually earned his music degree.

While still at Eton, Hubert sat for the Oxford Bachelor of Music exam, the youngest person ever to have done so. His exam exercise, a cantata: “O Lord, Thou hast cast us out” astonished the Heather Professor of Music, Sir Frederick Ouseley, and was triumphantly performed and published in 1867. In 1867 he left Eton and went to Exeter College, Oxford. He did not study music there, his music concerns taking second place, but read law and modern history. However, he did go to Stuttgart, Germany, at the urging of Henry Hugh Pierson, to learn re-orchestration, leaving him much more critical of Mendelssohn’s works.

When he left Exeter College, at his father’s behest, he felt obliged to try insurance work, as his father considered music only a pastime (too uncertain as a profession). He became an underwriter at Lloyd’s of London, 1870-77, but he found the work unappealing to his interests and inclinations. In 1872 he married Elizabeth Maude Herbert, and they had two daughters: Dorothea and Gwendolen. His in-laws agreed with his father that a conventional career was best, but it did not suit him. He began studying advanced piano with W. S. Bennett, but found it insufficient. He then took lessons with Edward Dannreuther, a wise and sympathetic teacher, who taught him Wagner’s music.

At the same time that Hubert’s compositions were coming to public notice (1875), he became a scholar of George Grove and soon an assistant editor for his new “Dictionary of Music and Musicians.” He contributed 123 articles to it. His own first work appeared in 1880. In 1883 he became professor of composition and musical history at the Royal College of Music (of which Grove was the head). In 1895 Parry succeeded Grove as head of the college, remaining in the post the remainder of his life. He also succeeded John Stainer as Heather Professor of Music at the University of Oxford (1900-1908). His academic duties were considerable and likely prevented him from composing as much as he might have. However, he was rated a very fine composer, nonetheless, of orchestrations, overtures, symphonies, and other music. He only attempted one opera, and it was /deemed unsuccessful.

Edward Elgar learned much of his craft from Parry’s articles in Grove’s Dictionary, and from those who studied under Parry at the Royal College, including Ralph Vaughn Williams, Gustav Holst, Frank Bridge, and John Ireland. Parry had the ability when teaching music to ascertain a student’s potential for creativity and direct it positively. In 1902 he was created a Baronet of Highnam Court in Gloucester. Parry was also an avid sailor and owned several yachts, becoming a member of the Royal Yacht Squadron in 1908, the only composer so honored. He was a Darwinian and a humanist. His daughter reiterated his liberal, non-conventional thinking. On medical advice he resigned his Oxford appointment in 1908 and thereafter produced some of his best known works.

He and his wife were taken up with the Suffrage Movement in 1916. He hated to see how WW1 ravaged young potential musical talent from England and Germany. In 1918 he contracted Spanish flu during the global pandemic and died at Knightscroft, Rustington, West Sussex. In 2015, 70 unpublished works of Parry’s were found hidden away in a family archive. It is thought some may never have been performed in public. The documents were sold at auction for a large sum. Other works he wrote include: “Studies of Great Composers” (1886), “The Art of Music” (1893), “The Evolution of the Art of Music” (1896), and “The Music of the 17th century” (1902). His best known work is probably his 1909 study of “Johann Sebastian Bach.”

In our hymnals today, we have music from Parry with “Sing Praise to the Lord” (LAUDATE DOMINUM), and “O Love of God, How Strong and True” (JERUSALEM). And one of the most famous anthems everyone has heard, “I Was Glad” (Psalm 122) is a masterpiece from his hand.

Here is a link to the first five stanzas being sung by the Redeemer Choir of Austin, Texas.