America’s National Day of Prayer, now observed on the first Thursday in May, has roots stretching back to the nation’s founding. While not formally established until 1952, the practice of national days of prayer and thanksgiving existed even before the country’s independence. The First Continental Congress in 1775 called for a National Day of Prayer, and later Presidents like George Washington and John Adams also issued proclamations for days of prayer and thanksgiving. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed a Congressional resolution in 1863 designating a day of fasting and prayer. President Harry S. Truman formally established the National Day of Prayer in 1952, designating it to coincide with the anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. President Ronald Reagan amended the law in 1988 to designate the first Thursday in May as the official National Day of Prayer.

Today it is observed with suggested guidelines from a national task force. In many communities, there is a noon prayer service on the steps of the city hall. In some schools, students gather around the flagpole before classes begin. And often nearby churches will join together for an evening prayer service. In each of these, ideas are provided to have prayers led by local leaders (not just pastors) focusing consecutively on such topics as our president, congress, and supreme court, local schools, police and fire personnel, schools and school boards, families, members of our armed forces, as well as specific topics such as poverty and joblessness, political issues, judicial decisions, international relations, crime, and especially for the need for a widespread revival that would return our people and culture to biblical principles of true righteousness.

In these prayer gatherings, not only are prayers offered, but also appropriate scriptures are read, interspersed with hymns about prayer. In every hymnal, one of the first to come to people’s minds on the topic of prayer is, not surprisingly, “Sweet Hour of Prayer.” Written perhaps by William W. Walford (1772-1850), it first appeared in print in the New York “Observer” on September 13, 1845. Little is known about him. At the time he may have written this, he was an elderly man and blind, and owned a small trinket shop in Coleshire, England. Day by day, he would sit in the chimney corner, carving and polishing pieces of bone to make shoehorns and other useful items for sale. As he worked, he would commune with the Lord in prayer, sometimes putting together thoughts to be shared in church the following Sunday.

Of obscure birth, Walford had no formal education, but the Lord had given him an amazing memory. He knew much of the Bible by heart, and was sometimes called upon to preach in a rural English church. He composed sermons in his head to deliver on Sundays. Having memorized a huge amount of the Bible, he quoted extended passages verbatim with unerring precision in his sermons, even giving chapter and verse, with hardly a slip.

At intervals he attempted poetry. There is a traditional account that one day in 1842, an American clergyman named Tom Salmon, pastor of the nearby Congregational Church, visited Mr. Walford’s little shop. As Salmon later is said to have reported, apparently, the old man talked with him about the theme of prayer, and the delight he took in fellowship with the Lord. Then he asked if Pastor Salmon would write down some lines of verse he had composed. Walford repeated two or three pieces which he had composed, and having no friend at home to commit them to paper, he had laid them up in the storehouse within his mind. “How will this do?” he asked, as he repeated the following lines, with a complacent smile that conveyed some light lines of fear lest he subject himself to criticism. Salmon rapidly copied the lines with his pencil as he uttered them, and three years later sent them for insertion in the New York “Observer,” writing “if you should think them worthy of preservation.”

However, there is no record of a blind, wood-carving preacher named William W. Walford ever living near Coleshill. Yet, there was a William W. Walford who was born at Bath in Somersetshire, England, in 1772. Educated at Homerton Academy, he became a Congregational minister, serving churches in Suffolk and Norfolk, and then worked as a classical tutor at Homerton. Also, he was minister at Uxbridge in Middlesex for two terms, after which he retired. His death occurred at Uxbridge on June 22, 1850.

Were the Walfords of Coleshill and Homerton the same man? There are vague references in the latter’s autobiography to a prolonged period of serious illness which might correspond to the break in his labors at Uxbridge, and it is possible that during this time he may have retired to Coleshill and pursued the hobby of woodcarving and done some preaching. His eyesight may have been affected as well, but Salmon may have been ignorant of his past. It is interesting that in 1836 Walford had written a book entitled “The Manner of Prayer,” which bears some striking resemblances to the hymn.

Others believe that perhaps Salmon or someone else had read Walford’s book to a blind, wood-carving preacher near Coleshill, possibly even with a similar name, who produced the poem, and Salmon’s calling the hymnwriter Walford may have just involved a slip of the memory. No one knows for sure. In any event, the hymn’s first appearance in a hymnbook, with words only, was in the 1859 edition of “Church Melodies,”compiled by Robert Turnbull and Thomas Hastings.

Hymns about prayer certainly need to be included in our hymnals. This is one of the most wonderful privileges and spiritual disciplines of the Christian life, both in private devotional dealings with the Lord as well as in public occasions of corporate prayer in worship services. Not only do we find prayers recorded in all parts of the Scriptures. At the center of our Bibles are 150 prayers, the Psalms that God has given as the inspired hymnal for the church. We recognize many different kinds of prayers in the liturgical language we see in our printed bulletins: prayers of invocation, adoration, supplication, and thanksgiving, along with pastoral prayers, offertory prayers, and prayers for illumination. In addition to general hymns about the subject of prayer, our hymnals also give us hymns that will fit every one of these kinds of prayers at the appropriate place in the worship service.

“Sweet Hour of Prayer” is one of those nineteenth century hymns which more liberal preachers and musicians today sometimes tend to denigrate as old-fashioned and unworthy of the dignity appropriate for corporate worship. Perhaps part of the reason is the word “sweet.” But we still use that word as an appropriate and positive description of everything from the picture of a lovely granddaughter to a romantic moment on a wedding anniversary. Of the four original stanzas, many hymnals today only include numbers 1 and 3. But all four are of value to the church.

The nature of the text is unusual, in that it is not actually addressed to the Lord, but rather to prayer itself as if it were personified and able to hear and respond to the statements made about it and requests made of it. Perhaps a way to deal with this is to imagine ourselves addressing the God to whom we pray, as each of the phrases would be fitting to include in our prayerful addresses to the Lord. Beyond that, we could perhaps think of ourselves addressing the Holy Spirit, since He is the one who shapes our prayers and presents them on our behalf at the throne of grace.

According to stanza 1, prayer is a relief and escape from the devil’s snare. Prayer does indeed free us from the bondage of undue attention to and anxiety about the world in which we live, a world that may indeed threaten us, but which has no interest whatsoever in viewing life from the perspective of being a beloved, adopted child of God. When we can remember that we live in the presence of the throne of the universe on which our heavenly Father sits, relief does indeed come even in those “seasons of distress and grief.” We can look back and recall the times in the past when our souls, through prayer have “oft escaped the tempter’s snare.”

Sweet hour of prayer! sweet hour of prayer! That calls me from a world of care,

And bids me at my Father’s throne Make all my wants and wishes known.

In seasons of distress and grief, My soul has often found relief

And oft escaped the tempter’s snare By thy return, sweet hour of prayer!

According to stanza 2, prayer is a time for joy and bliss. This will be true only for “those whose anxious spirits burn with strong desires for” this spiritual relief. We would have expected the phrase to speak of the return of the Lord, but it seems to be for the return of such a season of prayer. But perhaps those will often be found to be virtually synonymous, for it is during those sweet hours of prayer that “God my Savior shows His face.”

Sweet hour of prayer! sweet hour of prayer! The joy I feel, the bliss I share,

Of those whose anxious spirits burn With strong desires for thy return!

With such I hasten to the place Where God my Savior shows His face,

And gladly take my station there, And wait for thee, sweet hour of prayer!

According to stanza 3, prayer is an opportunity to make known our wishes, cares, and petitions to God. It pleases the Lord when we come to Him to express our love for Him and to renew our trust in Him. What a beautiful image we find in that of our prayers having wings with which to carry our petitions into God’s presence. The final line bears close resemblance to 1 Peter 5:7, where we are told to cast all our cares on Him as the one who cares for us.

Sweet hour of prayer! sweet hour of prayer! Thy wings shall my petition bear

To Him whose truth and faithfulness Engage the waiting soul to bless.

And since He bids me seek His face, Believe His Word, and trust His grace,

I’ll cast on Him my every care, And wait for thee, sweet hour of prayer!

According to stanza 4, prayer is communion with God and a glimpse of heaven. Great consolation is available for us when we envision ourselves, like Moses standing on Mount Pisgah, looking across into the promised land, not of Canaan, but of heaven. And the stanza goes on to create an imaginary (but believable!) video of ourselves, dropping our fleshly bodies to rise up and be transported across that divide, “passing through the air” into the land where we will no longer need those occasional hours of prayer, but will enjoy the bliss of eternal immediate access to the throne of grace.

Sweet hour of prayer! sweet hour of prayer! May I thy consolation share,

Till, from Mount Pisgah’s lofty height, I view my home and take my flight.

This robe of flesh I’ll drop and rise To seize the everlasting prize;

And shout, while passing through the air, ‘Farewell, farewell, sweet hour of prayer!’

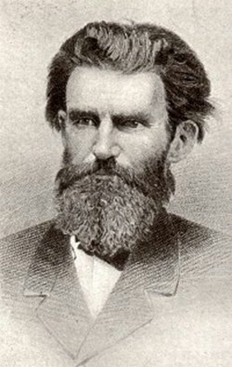

The tune SWEET HOUR was composed by William Batchelder Bradbury (1816-1868). After seeing the poem in a newspaper, he produced the music and published the hymn in his 1861 hymnbook “The Golden Chain.” Sometimes the source is given as Bradbury’s 1859 “Cottage Melodies.” However, the song did not appear in the first edition, but was apparently inserted in later printings after 1861. Bradbury was that famous gospel song writer who composed music for so many beloved gospel hymns such as “Just As I Am” (Charlotte Elliott), “The Solid Rock” (Edward Mote) and “He Leadeth Me” (Joseph H. Gilmore).

He was born on October 6, 1816, in York, Maine, where his father was the kleader of a church choir. He moved with his parents to Boston where he met Lowell Mason, and by 1834 was known as an organist. In 1840, he began teaching in Brooklyn, New York. In 1847 he went to Germany, where he studied harmony, composition, and vocal and instrumental music with the best masters. He is best known as a composer and publisher of a series of musical collections for choirs and schools. He was the author and compiler of fifty-nine books starting in 1841. In 1862, Bradbury found the poem “Jesus Loves Me” and wrote the music for it, adding the chorus, “Yes, Jesus loves me, Yes, Jesus Loves me …”

He died on January 7, 1868, in Bloomfield, New Jersey (now Montclair) at the age of 51. He was buried there in Bloomfield Cemetery.

Here is a link to a very gentle, devotional presentation of three of the stanzas of “Sweet Hour of Prayer,” for solo voice along with piano, cello, and strings.