There are two different calendar calculations in Christendom which result in the observation of different days for Christmas and for Easter. Christmas in the Eastern Orthodox world is always January 7, about the time that churches in the western world observe Epiphany. And while there are significant varieties of dates for Easter in both worlds, they are generally not the same date. The date is calculated based on the first new moon in the spring. The eastern churches follow the Julian calendar, whereas the western churches follow the Gregorian calendar. The result is that the two branches of Christendom will observe Easter (and Holy Week) on different dates. In the year that this study is being written, western Easter was April 17, and eastern Easter was April 24.

Christianity was officially and permanently (until now) divided by the “Great Schism” that took place in 1054, when the western Pope excommunicated the eastern church, and the eastern Patriarch excommunicate the western church. Over the centuries, political as well as theological disputes forced the two regions further and further apart. The western church encompassed most of what we now know as Europe, with Rome as the leading city. The eastern church encompassed areas from Greece and Turkey and further east, with Constantinople as the leading city. This eastern world became known as the Byzantine Church. In addition to the iconoclastic controversy (images) and the matter of the Spirit’s proceeding from Father and Son, language was also an issue, with the dominant ecclesiastical language in the east being Greek and the dominant ecclesiastical language in the west being Latin. The language issue affected not only worship, but also education and theological writing and disputation.

While a protestant today may initially feel that worship in the two branches of Christendom is similar, a closer look reveals significant differences. While both seem to be highly oriented toward a fixed and very formal ceremonial liturgy, several things stand out when examined more carefully. In the western Roman Catholic churches, 3-dimensional statues abound in the church sanctuary. But in the Eastern Orthodox churches, everything is 2-dimensional, with only flat paintings and mosaics permitted. In the western churches, there is a great variety of musical styles. But in the eastern churches, musical styles are limited to traditional forms. Both will include choirs, but few eastern churches will have any musical instruments. Another interesting characteristic is that the western churches focus on Calvary with multiple crucifixes, whereas the eastern churches focus on heaven, with many paintings and mosaics of the saints and angels around the throne.

There is a significant history of hymnody in both branches. By the 7th century, the influence of Pope Gregory (“the Great”), the sole official approved musical style was plainsong, which is often today called Gregorian Chant, and it was limited to monks and clergy. After the 5th century, there was no congregational singing until it was re-introduced by Luther (chorales) and Calvin (psalms) at the time of the Protestant Reformation. But in the eastern churches, congregational singing flourished with many hymns, and some of those texts (not music) are found in our hymnals today.

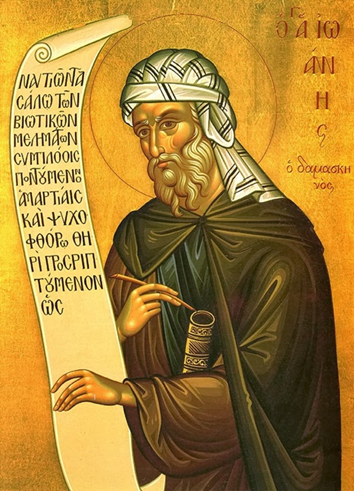

One of those is the Easter hymn, “The Day of Resurrection,” which comes to us from John of Damascus who lived about 655 to 745. His excellent literary and philosophical education in Damascus no doubt contributed to his renown as the author of many liturgical hymns in Constantinople, the seat of eastern Christianity well before the “Great Schism” already noted. Tradition suggests that he was a monk at the St. Sabas Monastery, known in Arabic as Mar Saba. This is a historically significant site overlooking the Kidron Valley, halfway between the Dead Sea and the Old City of Jerusalem. More recent scholarship by Greek scholar Vass Conticello places John of Damascus at Jerusalem Cathedral where he was the theological advisor of Patriarch John V of Jerusalem. Though most likely buried at St. Sabas, his relics were moved to Constantinople at a later date. John’s father, a Christian, was an important official at the court of the Muslim caliph in Damascus. After his father’s death, John assumed that position and lived in wealth and honor. At about the age of forty, however, he became dissatisfied with his life, gave away his possessions, freed his slaves, and entered the desert monastery of St. Sabas.

There is no doubt, however, that John of Damascus was one of the most important hymnographers of the Byzantine (Eastern) Church. His name appears often in manuscripts, although not all the hymns attributed to him may have been his. It was a common practice during this time, and indeed for hundreds of years after this, to ascribe the name of a famous or acclaimed author (or even composer) to a work. As well as being a hymn writer, John of Damascus was a prominent theologian, and late in life he became the bishop of the church in Jerusalem. He has been described as, “The last but one of the Fathers of the Eastern Church, and the greatest of her poets.”

St. John of Damascus composed in one of three major forms of Christian poetry, the kanon, called by Dimitri Conomos, “The most important event in the history of Byzantine hymnody. The kanon replaced earlier forms of hymnody that were linked to nine biblical canticles and expanded the complexity, variety of themes, and forms of hymns used in the liturgy to include major Christian festivals. St. John Damascene, the most accomplished composer of this form, wrote “Anastaseôs hêmera” as the kanon for Easter Day, translated later by John Mason Neale (1818-1866) as “The Day of Resurrection.” Neale was the great hymnologist of England’s Oxford Movement in the mid-nineteenth century.

This hymn and “Come, Ye Faithful, Raise the Strain” were both written by John as hymns from the “Golden Canon,” a series of Easter poems linking the mighty acts of God. The poetry of the Golden Canon, sometimes called the “Queen of Canons,” is said to be the finest example of Greek sacred poetry. Methodist hymnology scholar Dr. Carlton Young compares the systematic development of Byzantine chant (kanon) by John of Damascus, the most important dogmatic theologian of the Eastern church, to the role played earlier by Pope Gregory I, also known as Gregory the Great (ca. 540-604) in developing the Western chant tradition known as Gregorian Chant or plainsong.

“The Day of Resurrection” has become a regular part of the musical celebrations of Easter in the western churches, both Roman Catholic and protestant. John Mason Neale includes a description of a nineteenth-century observer of this ancient Easter liturgy, the most important festival of Christians, in which this hymn would have been sung with the explosive energy of Easter’s triumph.

As midnight approached, the archbishop, with his priests, accompanied by the King and Queen, left the Church and stationed themselves on the platform, which was raised considerably from the ground, so that they were distinctly seen by the people. Every one now remained in breathless expectation, holding unlighted tapers in readiness when the glad moment should arrive . . .. Suddenly, a single report of a cannon announced that twelve o'clock had struck and that Easter Day had begun; then the old Archbishop, elevating the cross, exclaimed in a loud, exulting tone, ‘Christos anesti!’ ‘Christ is risen!’ and instantly every single individual of all that host took up the cry. … At that same moment, the oppressive darkness was succeeded by a blaze of light from thousands of tapers which . . . seemed to send streams of fire in all directions . . .

Bands of music strike up their gayest strains. . . . and above the mingling of many sounds, . . . the aged priests were distinctly heard chanting forth the glorious old hymn of victory, ‘The day of resurrection/Earth, tell it out abroad.’

What a sight that must have been!

Stanza 1 almost explodes with joy in an announcement of this most festive day of the church year. It makes the wonderful connection between the Passover of the Old Testament, when God brought His people out of bondage to Egypt with the shedding of the blood of a lamb, and the Passover of the New Testament, as God has brought His people out of bondage to sin with the shedding of the blood of the Lamb of God. Moses was the deliverer then as a “type” of which Jesus was the fulfilment, the ”antitype.” But unlike the lambs in Egypt, the Lamb of God did not stay dead, but rose again, triumphing over death and the grave.

The day of resurrection! Earth, tell it out abroad;

the Passover of gladness, the Passover of God.

From death to life eternal, from earth unto the sky,

our Christ hath brought us over, with hymns of victory.

Stanza 2 expresses the longing of every believing heart to be made pure from evil, washed in His blood, declared justified through faith in His substitutionary atoning sacrifice. With these new hearts we long to see past all the remaining strife in our world to view “the Lord in rays eternal of resurrection light.” And instead of the sounds of the world’s anger and bitterness and war, we long to hear Jesus’ voice greeting us, and our responding with our songs of victory.

Our hearts be pure from evil, that we may see aright

the Lord in rays eternal of resurrection light;

and listening to his accents, may hear, so calm and plain,

his own “All hail!” and, hearing, may raise the victor strain.

Stanza 3 calls all creation, both heavens and earth, to join in jubilant song celebrating this triumph. That includes “all things seen and unseen”. Oh, how we long for that day when this will be realized, as every knee will bow and every tongue confess that He is Lord, singing together, “Worthy is the Lamb!” Every Easter should be a celebration in anticipation of that day. Indeed, should not every Lord’s day worship be the same? Our Sunday worship ought to be a rehearsal for that day when we shall see Him, and sing to Him, face to face!

Now let the heavens be joyful! Let earth the song begin!

Let the round world keep triumph, and all that is therein!

Let all things seen and unseen, their notes in gladness blend,

for Christ the Lord hath risen, our joy that hath no end.

Though sometimes sung to the tune ELLACOMBE (“Hosanna, Loud Hosanna”), it is usually sung to the tune LANCASHIRE (“Lead On, O King Eternal”). The composer of LANCASHIRE was the London musician, Henry Thomas Smart (1813-1879), who also composed the tune REGENT SQUARE which is used with the texts “Angels from the Realms of Glory,” “Worship Christ, the Risen King,” and “Christ Is Made the Sure Foundation.” He gave up a career in the legal profession for one in music. Although largely self taught, he became proficient in organ playing and composition, and he was a music teacher and critic. Organist in a number of London churches, including St. Luke’s, Old Street (1844-1864), and St. Pancras (1864-1869), Smart was famous for his extemporizations and for his accompaniment of congregational singing.

He became completely blind at the age of fifty-two, but his remarkable memory enabled him to continue playing the organ. Fascinated by organs as a youth, Smart designed organs for important places such as St. Andrew Hall in Glasgow and the Town Hall in Leeds. He composed an opera, oratorios, part-songs, some instrumental music, and many hymn tunes, as well as a large number of works for organ and choir. He edited the “Choralebook” (1858), the English Presbyterian “Psalms and Hymns for Divine Worship” (1867), and the Scottish “Presbyterian Hymnal” (1875). Some of his hymn tunes were first published in “Hymns Ancient and Modern” (1861).

Here is a congregational singing of the hymn, supported by choir and organ.