These hymn studies focus primarily on the texts and the authors. But we also take note of the composers of the music with which we sing those words. In this study, we will look at both elements of this triumphant Easter hymn, Thine Be the Glory. A popular Easter hymn, this celebrates the glory that is associated with Jesus because of His resurrection. The heart of the message of Easter, is of course, the fact of the resurrection. One of the primary biblical explanations of its importance comes in 1 Corinthians 15, where Paul wrote that if Christ has not been raised from the dead, then our faith is futile and we are still in our sins. It’s important that we not settle for sentimental messages about “resurrection faith,” focusing on butterflies and spring leaves and bunny rabbits, and how we should look for bright things in our lives to come out of dark times. No, it’s about resurrection FACT, not resurrection FAITH. It’s not about us, it’s about Jesus!

The text to Thine Be the Glory was originally written in 1884 in French as “A Toi la gloire, ô Ressuscité.” The author, French-speaking Edmond L. Budry (1854-1932), was the pastor of the Free Evangelical Church of the Canton of Vevey, Switzerland. That was part of the church that had broken away from the increasingly liberal main Calvinistic denomination in Switzerland. He was reported to have been inspired to write it after the death of his first wife, Marie de Vayenborg in Lausanne. Budry was from the north shore of Lake Geneva, from the beautiful town of Vevey, a town so ancient that it was mentioned by the writer Ptolemy back in the Second Century. From a very strict evangelical background, he studied theology with a free church faculty in Lausanne. In 1881 he went to be pastor to evangelical congregations at Cully and Sainte-Croix and in 1889 he moved to become pastor of the Free Church at Vevey, where he was to remain for 35 years, until his retirement in 1923.

Budry was a proficient linguist, and as well as writing his own works in French, was often asked to make translations of favorite German or English hymns. He preferred to rewrite the texts, trying to improve on the original, and often freely adapted old Latin hymns. He wrote over sixty chorales, some of which appeared in French hymnbooks. The inspiration for this particular hymn, according to Budry’s friend Paul Laufer, came from the words of Friedrich-Heinrich Ranke (1798-1876). Budry freely adapted Ranke’s Advent text and transformed it into an Easter hymn.

It would be twenty years before Thine Be the Glory gained fame by being published in the YMCA hymnbook at Lausanne in 1904. It would be twenty more before it became known to the English-speaking world, after it was translated into English in 1923, the year of Budry’s retirement, by Baptist minister Richard Birch Hoyle (1875-1939). The first appearance of the English text of the hymn was in 1925 in the hymnbook Cantate Domino published for the World Student Christian Federation in Geneva.

The hymn has become popular in many nations. It is a favorite choice for weddings in America, either as a processional or as a congregational hymn. In 1957 in the Netherlands, Christian author/philosopher Calvin Seerveld used it for his wedding, and it has become common as a congregational hymn there on such occasions, and especially during funerals and weddings of the Dutch royal family. In Spain, it is used as a wedding hymn with lyrics based on Psalm 96. It was translated into Danish in 1993, and is used both for weddings and funerals. In England it is often used at Easter services involving the British royal family. It was also played during a service of thanksgiving in commemoration of Queen Elizabeth’s 80th birthday. It is traditionally played during the last night of the Proms in the United Kingdom with attendees whistling the tune. In Ireland it traditionally closes the Christmas Eve services at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin But of course it is most often used as a congregational hymn in Easter Sunday celebrations.

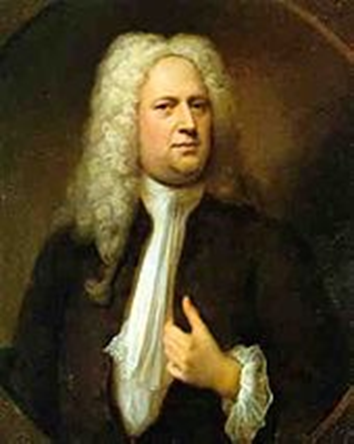

But the most famous name associated with Thine Be the Glory is, of course, George Frideric Handel (1685-1759), composer of the classic Christmas and Easter oratorio “Messiah.” The tune we use in singing this hymn was written by Handel in 1747, intended for use as a processional in his “Joshua” oratorio. However, when it was played, it was popular enough that Handel added it to later versions of “Judas Maccabaeus,” where it was set to the chorus, “See, the conquering hero comes.” In 1796, Ludwig Van Beethoven composed twelve variations on it for piano and cello. The melody was first developed as a hymn tune by the Methodist musician Thomas Butts, who included it in his collection Harmonia Sacra, a collection that was very influential in shaping John Wesley’s collection of hymns, “Sacred Melody.” Budry wrote his original words to fit the tune, and it is hard to imagine they would have such force in any other setting. The tune today carries the name MACCABAEUS.

Handel was born in Halle, Germany in 1685, the same year as Johann Sebastian Bach and Domenico Scarlatti. His father was a prominent and successful barber-surgeon for the local duke and decided early on that his son would study civil law. But George was drawn to more artistic things, especially music and the sounds instruments could make. His father forbade him from pursuing what he called “musical nonsense.” It has been reported that by some means young George was able to smuggle a small clavichord into a tiny room at the top of the house. Then at night when the rest of the family was asleep, George would silently creep up to that room to practice. And so it came as a complete surprise to family and friends at church one day when eight year-old George climbed up on the organ bench and played the postlude!

When Handel was still a young boy, he had the opportunity to play the organ for the duke’s court in Weissenfels. It was there that Handel met composer and organist Frideric Wilhelm Zachow. Zachow was impressed with Handel’s potential and invited Handel to become his pupil. Under Zachow’s tutelage, Handel mastered composing for the organ, the oboe, and the violin alike by the time he was 10 years old. From the age of 11 to the time he was 16 or 17, Handel composed church cantatas and chamber music that, being written for a small audience, failed to garner much attention and have since been lost to time.

Eventually George did enroll in law school, but music continued to dominate his imagination. He left school and began to travel to learn as much as he could about musical styles. He finally settled in London in 1711 at the age of 26. It was there that his musical career blossomed. His operas and oratorios became very popular and he was welcomed into England’s musical and social circles. After the debut of his opera, Rinaldo, Handel spent the next few years writing and performing for English royalty, including Queen Anne and King George I. Then, in 1719, Handel was invited to become the Master of the Orchestra at the Royal Academy of Music, the first Italian opera company in London. Handel eagerly accepted. He produced several operas with the Royal Academy of Music that, while well-liked, were not especially lucrative for the struggling academy.

In place of operas, oratorios became Handel’s new format of choice. Oratorios, large-scale concert pieces, immediately caught on with audiences and proved quite lucrative. The fact that oratorios didn’t require elaborate costumes and sets, as operas did, also meant that they cost far less to produce. Handel revised a number of Italian operas to fit this new format, translating them into English for the London audience. His oratorios became the latest craze in London and were soon made a regular feature of the opera season. In 1735, during Lent alone, Handel produced more than 14 concerts made up primarily of oratorios. In 1741 Dublin’s Lord Lieutenant commissioned Handel to write a new oratorio based on a biblical libretto assembled by art patron Charles Jennens. As a result, Handel’s most famous oratorio, “Messiah,” made its debut at the New Music Hall in Dublin in April 1742. He continued to compose a long string of oratorios throughout the remainder of his life, including “Maccabaeus.” In addition to choral works, he composed many instrumental works, including six concertos for organ and orchestra, “Water Music,” and “Music for Royal Fireworks,” all of which continue to be performed regularly today.

Over the course of his musical career, Handel, exhausted by stress, endured a number of potentially debilitating problems with his physical health. He is also believed to have suffered from anxiety and depression. Yet somehow, Handel, who was known to laugh in the face of adversity, remained virtually undeterred in his determination to keep making music. In the spring of 1737, Handel suffered a stroke that impaired the movement of his right hand. His fans worried that he would never compose again. But after only six weeks of recuperation in Aix-la-Chapelle, Handel was fully recovered. He went back to London and not only returned to composing, but made a comeback at playing the organ as well.

Six years later, Handel suffered a second springtime stroke. However, he stunned audiences once again with a speedy recovery, followed by a prolific stream of ambitious oratorios. Handel’s three-act oratorio “Samson,” which premiered in London in 1743, reflected how Handel related to the character’s blindness through his own firsthand experience with the progressive degeneration of his sight. By 1750, Handel had entirely lost sight in his left eye. He forged on, however, composing the oratorio “Jephtha,” which also contained a reference to obscured vision. In 1752 Handel lost sight in his other eye and was rendered completely blind. As always before, Handel’s passionate pursuit of music propelled him forward. He kept on performing and composing, relying on his sharp memory to compensate when necessary, and remained actively involved in productions of his work until his dying day.

On April 14, 1759, Handel died in bed at his rented house at 25 Brook Street, in the Mayfair district of London. The Baroque composer and organist was 74 years old. Handel was known for being a generous man, even in death. Having never married or fathered children, his will divided his assets among his servants and several charities, including the Foundling Hospital. He even donated the money to pay for his own funeral so that none of his loved ones would bear the financial burden. Handel was buried in Westminster Abbey a week after he died. Following his death, biographical documents began to circulate, and George Handel soon took on legendary status posthumously. While we make little mention of stories related to the composition of Messiah, that will deserve elaboration in another study.

Stanza 1 summarizes the glorious Gospel account of Jesus’ resurrection, reminding us not only of the facts (the angels, the stone, and the grave clothes) but also of the meaning. This was the victory over death, and not only for Jesus, the first fruits, but also for those who have put their faith in Him and can be assured of their own resurrection. In all of this, the dazzling glory of the gospel shines brilliantly.

Thine be the glory, risen, conquering Son,

endless is the vict’ry Thou o’er death hast won;

angels in bright raiment rolled the stone away,

kept the folded grave-clothes where Thy body lay.

Thine be the glory, risen, conquering Son,

endless is the vict’ry Thou o’er death hast won.

Stanza 2 brings us directly into the glory of the resurrection as it imagines the risen Savior actually meeting us face to face, with the result that the fear and gloom that would have been there for the disciples on the day of his crucifixion had then been scattered. And we are scattered as well to share the good news that death has lost its sting, as Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 15:55.

Lo! Jesus meets us, risen from the tomb;

lovingly He greets us, scatters fear and gloom;

let the Church with gladness hymns of triumph sing,

for her Lord now liveth; death hath lost its sting.

Thine be the glory, risen, conquering Son,

endless is the vict’ry Thou o’er death hast won.

Stanza 3 moves from our current situation all the way to the end when we will be brought safely home to heaven, figuratively crossing the Jordan into the Promised Land. We can live now without doubt, and can live as more than conquerors (Romans 8:35-39), since we are not alone, but have this risen Savior with us to “aid us in our strife.”

No more we doubt Thee, glorious Prince of life;

life is naught without Thee: aid us in our strife;

make us more than conqu’rors, thro’ Thy deathless love:

bring us safe thro’ Jordan to Thy home above.

Thine be the glory, risen, conquering Son,

endless is the vict’ry Thou o’er death hast won.

Here is a link to the hymn sung at the chapel of King’s College in Cambridge. Notice the lovely descant on the final stanza.