In the Gospels, the Holy Spirit has given us significant details about Jesus’ intense struggles in the Garden of Gethsemane. As theologians have taught us, the deepest pain was not from the scourging or the crown of thorns or the nails, or even the taunting of the crowd. No, it was the anguish of suffering the Father’s wrath in our place as “He who knew no sin became sin for us.” It was not the abandonment of His disciples; it was being forsaken by His Father, with whom He had enjoyed such glorious love from eternity, and being there made a curse for us. And He was already beginning to experience that in the Garden. Truly we should say as we look at Him there, “That should have been me!”

The Savior’s distress was very real. It was Doctor Luke who has written that Jesus’ sweat became like great drops of blood falling down to the ground. (Luke 22:44) Physicians today call this rare condition hematidrosis when blood pressure becomes so elevated (as from intense anxiety) that blood is forced out of the capillaries into the sweat glands. And it’s in the book of Hebrews that we read that Jesus “offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears.” (5:7)

In the hymn ‘Tis Midnight and Olive’s Brow, we sing of the profound pain in His soul as Jesus was entering into that intense spiritual darkness. In each stanza, the hymn repeatedly begins “’Tis Midnight.” Having celebrated the Passover, and instituted the Lord’s Supper, with the disciples, He had led them out that night to the Garden of Gethsemane, in the midst of a grove of olive trees where He had frequently gone before for prayer. It was a relatively short walk from the city of Jerusalem across the Kidron Valley to the rounded hilltop of the Mount of Olives. He asked the disciples to watch and pray while He went aside by Himself to wrestle in prayer. But in their weariness, they repeatedly fell asleep. The hymn sets the scene for us at midnight.

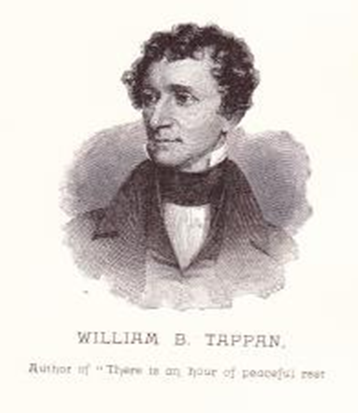

It was written in 1822 by William Bingham Tappan (1794-1849) at the young age of only 28. He was born in Beverley, MA and in 1810 was apprenticed to a clockmaker in Boston, his father having died when he was only 12 years old. In 1815 he moved to Philadelphia where he was engaged in the clockmaking and repair business for a time. In 1822 he became Superintendent of the American Sunday School Union. In 1840 he was licensed to preach with the Congregationalists and became known as a successful evangelist, preaching in several states. He died suddenly of cholera at West Needham, MA on June 18, 1849. He has left us ten volumes of poetry and a few hymns, the best known being ‘Tis Midnight and On Olive’s Brow.

Stanza 1 sets the place and time, on the Mount of Olives during the middle of the night. What did Tappan mean about the star being dimmed? Was it simply the stars of the night obscured behind clouds? Was it the star of Bethlehem that was no longer shining? Or was it the star of Jesus’ popularity with the crowds from His miracles and teaching that was now dimmed? Whichever was the case, the Suffering Savior prophesied by Isaiah 53 was praying alone.

‘Tis midnight; and on Olive’s brow The star is dimmed that lately shone;

‘Tis midnight; in the garden now The suffering Savior prays alone.

Stanza 2 emphasizes the fact that Jesus was alone. He had left the twelve in another part of the garden. There is symbolic truth in this, because the work of atonement was something that only Jesus could do, and that involves no partnership from us. The Gospels show a very close relationship between Jesus and John. He was the only one of the twelve to be at the cross, and was the one to whom Jesus committed the on-going care of His mother, Mary. But at this point, even John was sound asleep.

‘Tis midnight; and from all removed, Emmanuel wrestles lone with fears

E’en the disciple whom He loved Heeds not his Master’s grief and tears.

Stanza 3 is the most theologically-oriented part of the text. It’s a very brief phrase, but extremely important to a correct understand of the cross. It was “for other’s guilt” that Jesus died. “He who knew no sin became sin for us.” (2 Corinthians 5:21) Once again, the central doctrine of the substitutionary atonement is prominent in our hymnody. That’s because it is prominent in Scripture. The Suffering Servant Song in Isaiah 52 and 53 tells us that we have gone astray, and the Lord has laid our iniquity on Him. The stanza also includes reference to Jesus’ sweating as it were great drops of blood. But then the stanza also include a very puzzling statement that He was not forsaken by His God. How can this be, since the Gospels clearly identify as one of “the seven last words” Jesus’ quoting from Psalm 22, “My God, my God, why have You forsaken Me?” He was indeed forsaken – on the cross! And yet it must have been the Father who gracious sent an angel to minister to Jesus – in the Garden. (Luke 22:43)

‘Tis midnight; and for others’ guilt The Man of Sorrows weeps in blood;

Yet He that hath in anguish knelt Is not forsaken by His God.

Stanza 4 has been revised in our hymnals to speak of “heav’nly plains” instead of Tappan’s original text, “ether plains.” The word “ether” refers to ethereal, which is of course an unfamiliar phrase today. Changing it to “heav’nly” is entirely consistent with Tappan’s meaning. And what is the song that Tappan had in mind? Here, poetic license is utilized to imagine angels singing to “sweetly soothe the Savior’s woe,” music that no “mortal” could have heard.

‘Tis midnight; from the heav’nly plains Is borne the song that angels know;

Unheard by mortals are the strains That sweetly soothe the Savior’s woe.

The tune, OLIVE’S BROW, was composed for this text by William Batchelder Bradbury (1816-1868). It first appeared in his 1863 work The Shawm. Bradbury provided well-known tunes for several hymns, such as Sweet Hour of Prayer and He Leadeth Me.

Here is a recording of the singing of Tappan’s hymn.