That was an amazing night both historically and theologically. Jesus met with the twelve for that special meal that was celebrated each year at Passover. For about fourteen centuries, Jews observed the exodus in the way commanded through Moses. It was a commemoration meal of God having set them free from bondage in Egypt. In its first institution, gathering in their homes, they ate the flesh of the Passover lamb and applied its blood to the doorposts of their homes. That saved them as the angel of death passed over the land, bringing death to every first-born who was not “covered” by that blood. It was the next day that the Lord led them out to cross the Red Sea and move toward the Promised Land.

This Maundy Thursday was the moment when Jesus instituted the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. The meal in the Upper Room marks the transition from picture to reality, from the blood of animals to the blood of the Lamb of God. It sets forth the continuity between the Old and the New Testament since both Passover and the Lord’s Supper point to the same thing: freedom from bondage through the shedding of the blood of a lamb. But this also marks the dramatic transition from the Old Covenant of provisional symbols to the New Covenant of final fulfillment. As Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 5:7, “Christ our Passover Lamb has been sacrificed.”

When we gather in our churches on Maundy Thursday evening, we not only recount the events of that night. We meditate on Jesus’ washing the disciples’ feet, of His Upper Room discourse with its glorious promises of comfort, and of His going into the intense agony in the Garden of Gethsemane before Judas arrived with the temple guards to arrest Jesus and bring Him to the repeated trials of the early morning hours. Our Maundy Thursday services will include the celebration of the Lord’s Supper, celebrating the fulfilment of prophecies like that in Isaiah 53 as the Savior offered Himself as the propitiatory sacrificial substitute to suffer in His soul and body the wrath of God that we deserved, in order to redeem us.

Maundy Thursday should not only take us back to the Upper Room to remember and understand what Jesus has done for us. We also ought to be faithful to the mandate that led to the day having been named Maundy, and that is to love one another even as He has loved us. His love was unique in that it was a once for all sacrifice for our sins. In contrast to that, our love is that of on-going grateful obedience to and imitation of the selflessness of that love which we should be cultivating and demonstrating toward one another. As we come to the table of the Lord on this night, our eyes should not only be lifted up to worship the Lamb of God slain for us, but also should be looking around to see who needs to be touched by the Savior’s love through the kindness we show to them. May the Lord grant us greater devotion to the Savior, and also greater sensitivity to the needs of those near us.

Among the many hymns that fit in that service, reviewing the darkness of that night, is the hymn “ ‘Twas on That Night When Doomed to Know.” It describes that moment when Jesus told the disciples what He was doing with the familiar elements of that meal, putting entirely new meaning on the bread and the wine. Most of the six stanzas of the hymn are in quotation marks, placing Jesus’ own words directly from Scripture into the narration of the hymn text. The hymn is based especially on Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 11:23, “The Lord Jesus the same night in which He was betrayed took bread.”

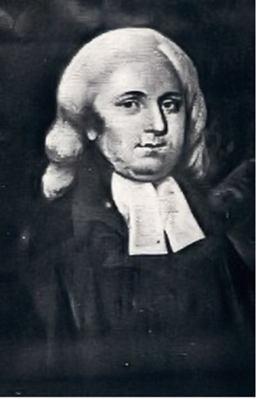

The hymn was written by John Morison (sometimes spelled Morrison) in 1781. He was born in Aberdeenshire, Scotland in 1750, the same year that Johann Sebastian Bach died in Germany and just two decades before the events of the 18th century American Revolution. He studied at the University of Aberdeen (King’s College) where he graduated. M. A. in 1771. In 1780 he became parish minister of Canisbay, Caithness. He was awarded the degree of D. D. from the University of Edinburgh in 1792. He was one of a number of Scottish clergy who added Scripture paraphrases like this one to the collections of Psalms that were the standard congregational song of the Church of Scotland. He died at Canisbay in 1798 at the relatively young age of 48 and was interred in an umarked grave. A plaque to his memory was placed in the church in Cairney, Aberdeenshire. It reads as follows, though with different spelling and a different birth year.

Sacred to the Memory of

THE REV. JOHN MORRISON D.D.

Poet and Divine

Born at Whitehill, Cairney, 18th Sept. 1746

Ordained Minister of the Parish of Cansibay,

26th Sept. 1780; Died there, 12th June 1798.

To him the Church of Scotland owes

Seven of the finest of her

Paraphrases: -

XIX,XXI,XXVII,XXVIII,XXIX,XXX,&XXV.

In Gratitude for which this Tablet

Was erected by the Church Guilds of

His native parish and other friends.

His power increasing still shall spread.

His reign no end shall know;

Justice shall guard his throne above,

And peace abound below. Par. XIX.6.

The song is very appropriate to help us prepare our minds for partaking of the Lord’s supper. As we do so, we are obeying Jesus’ command, “Do this in remembrance of Me.” (Luke 22:19)

Stanza 1 centers upon the bread. It sets it in the context of Jesus’ knowing what was taking place as the rage of earthly and demonic foes were being marshaled against Him.

‘Twas on that night when doomed to know the eager rage of ev’ry foe,

that night in which He was betrayed, the Savior of the world took bread.

Stanza 2 centers upon the meaning of the bread. It was to be a symbol of His body broken for us, and which in the sacrament becomes spiritual nourishment for our souls.

And after thanks and glory giv’n to Him that rules in earth and heav’n,

that symbol of His flesh He broke, and thus to all His foll’wers spoke:

Stanza 3 centers upon what Jesus said about the bread. It is more than a mere memorial, but actually becomes the instrument through which He is spiritually present.

“My broken body thus I give for you, for all. Take, eat, and live.

And oft the sacred rite renew that brings My saving love to view.”

Stanza 4 centers upon the cup. What beautiful literary elegance as Morison wrote of kindness glowing in Jesus’ bosom and salvation flowing from His lips.

Then in His hands the cup He raised, and God anew He thanked and praised,

while kindness in His bosom glowed, and from His lips salvation flowed.

Stanza 5 centers upon the meaning of the cup. Three things are named for our benefit: cleansing the soul, sealing the covenant, and revealing heaven’s eternal grace.

“My blood I thus pour forth,” He cries, “to cleanse the soul in sin that lies;

in this the covenant is sealed, and heav’n’s eternal grace revealed.

Stanza 6 centers upon what Jesus said about the cup. It reminds us of His instructing us to do this in remembrance of Him.

“With love to man this cup is fraught; let all partake the sacred draught;

through latest ages let it pour, in mem’ry of My dying hour.”

The tune ROCKINGHAM OLD is of unknown origin. Some scholars think that it is derived from the tune BROMLEY by Jeremiah Clarke (1669-1707), 17th century organist at London’s Westminster Abbey. Others believe that it originated with Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach (1714-1788). It first appeared anonymously in “A Second Supplement to Psalmody in Miniature,” about 1770-1780, edited by Aaron Williams (1731-1776). The modern arrangement or adaptation was made by Edward Miller, who was born on Oct. 30, 1735 (some sources say 1731), at Norwich, England. Apprenticed to his father, who was a paver, he ran away to study music under Charles Burney at King’s Lynn and at one time was a flautist in the orchestra of George Frederick Handel, receiving a doctorate degree in music from Cambridge University in 1786. An organist, Miller lived for fifty years at Doncaster in South Yorkshire, England, composing harpsichord sonatas, and his hymn tunes were published in numerous Psalm books. This version of the tune first appeared in 1790 in “The Psalms of David for the Use of Parish Churches.” Also, he published books on composition in 1787, the performance of psalmody in 1791, and the history of Doncaster in 1804. He died on Sept. 12, 1807, at Doncaster.

Here you can watch, listen, and even sing along with the text. This version does not include all six stanzas.