When we sing our Christmas carols, it’s helpful to know something about their origin in regard to both words and music. Sometimes the stories attached to them are quite surprising. And here in the case of “What Child Is This?” the surprise includes a possible musical connection to the infamous 16th century British monarch, Henry VIII, and a love ballad to “my lady Greensleeves.”

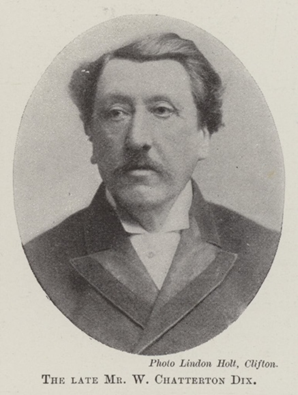

But of first importance is the origin and meaning of the text. The words come from the pen of an insurance agent by the name of William Chatterton Dix (1837-1898), an Anglican layman, the son of a surgeon in Bristol, England. He spent most of his life as a businessman, working as a manager for the Maritime Insurance Company in Glasgow, Scotland. We know of his church affiliation only through his hymns.

Dix wrote “What Child Is This?” at Christmas time in 1865 at the age of 29 when he was afflicted by an unexpected and severe illness that resulted in his being bedridden and suffering from severe depression. This near-death experience was used by the Lord to bring about a significant spiritual renewal in his heart while recovering. During that time, he read the Bible “comprehensively” and was motived to write a number of hymns, including “Alleluia! Sing to Jesus!” and the Epiphany hymn “As with Gladness Men of Old.”

While William continued working in insurance, he used his love of writing as a form of worship. His favorite form of writing was poetry, and while most of his compositions stayed hidden within a writing desk at home, there was this one poem that he wanted to share beyond his desk drawer. The poem was called “What Child Is This?” Not being musically inclined, he searched for an established melody to pair with his poem. There was one such melody that gave the poem of sense of grandeur and significance, a classic melody already beloved within the Christmas season, GREENSLEEVES. Slowly, the combined poem and melody began to spread from church to church as Christmas seasons came and went.

“What Child Is This?” was first published in 1871, six years after its origin. It was featured in an influential and prestigious collection of carols in the United Kingdom, titled “Christmas Carols Old and New.” The hymnal was edited by Sir John Stainer (composer of the beloved 1887 choral passion work, “The Crucifixion”) and Henry Ramsden Bramley. Stainer was primarily responsible for harmonizing the musical setting of Dix’s hymn. In our day, the carol has gained great popularity in the USA, in spite of its roots being in Great Britain.

The meaningful lyrics and the soulful melody of the carol evokes a moving scenario. It conveys the amazing reality that God Himself, in the second person of the Trinity, has been supernaturally transformed into a true human being through this baby, and that the Almighty has arrived to rescue His elect. It’s a certain and clear sign of hope, which the early witnesses went on to declare with courage and ingenuity. This musical tribute is fitting, as humans marvel and wonder in amazement while pondering this awesome question, “What Child Is This?”

And the fact that the hymn repeatedly asks questions is one of the unique dimensions of the song. The opening question in the first two stanzas is then answered in the refrain, before the final stanza calls on all to join the Magi bringing costly gifts of adoration. David Mathis, executive editor of Desiring God, wrote this about how valuable questions can be.

As a child, I was not impressed with a Christmas song that asked a question everyone already knew the answer to. “ It’s Jesus, of course.” We all know that — even the kids know that.

What I didn’t yet understand is that questions aren’t just for solving problems and requesting new information. Sometimes questions make a point. We call those “rhetorical questions.” Other times the form of a question expresses awe and wonder about something we know to be true, but find almost too good to be true. It’s too good to simply say it directly like we say everything else.

When the disciples found themselves in a great windstorm, with waves breaking into the boat, and Jesus calmed the storm, they said to one another, “Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him?” (Mark 4:41). They knew the answer from Scripture. Only God himself can still the seas (Psalm 65:7; 89:9; 107:29), somehow, must be God. But it was too wonderful just to say. This new revelation of Jesus’s glory was too stupendous to keep quiet, and too remarkable not to say it in some fresh way. God himself had become man and was in the boat with them. “Who then is this?”

It’s in a similar vein that we say at Christmas, “What child is this?” We know the answer. It has been plainly revealed. And it is almost too wonderful to be true. God himself has become man in this baby, and has come to rescue us. The eternal Word has become flesh and dwells among us (John 1:14). It is clear and certain. We must say it straightforwardly and with courage. And it is fitting that at times, like Christmas, we wonder, we marvel, we declare in awe, “What child is this?”

Hymnologist Albert Bailey noted that some of Dix’s hymns are “horribly sentimental,” but on the whole says, “his hymns are simple, reverent, sincere, imaginative, not above the average comprehension, and two of them at least have proved to be continuously serviceable.” Of course, those two are “As With Gladness Men of Old” and “What Child Is This?”

The lyrics were inspired by one of Dix’s poems titled “The Manger Throne.” It urges humanity to accept Christ. The eloquent melody is haunting, and its beautiful essence reiterates the “Adoration of the Shepherds” who paid a visit to Jesus during the nativity. The lyrics pose questions that reflect what the shepherds might have been pondering during the encounter, and subsequently offers a response to such questions.

Some versions of the hymn today use the final two staffs as a refrain at the end of each stanza. Most however include additional text for the conclusions, carrying the wondering contemplation even further in worship, rather than having a repeated refrain. These are identified here as the 2nd half of each stanza.

Stanza 1 (1st half) asks for the true identity of this child. Dix condenses Luke 2:8-16 into a singe stanza, painting a picture of a classic nativity scene with Christ sleeping on “Mary’s lap” while angels sing “anthems sweet” and “shepherd’s watch are keeping.”

What Child is this, who, laid to rest, On Mary’s lap is sleeping?

Whom angels greet with anthems sweet, While shepherds watch are keeping

Stanza 1 (2nd half ) gives the answer to the questions. It settles the identity of this child, He is “Christ, the King.” Dix gives a dramatic contrast, faithful to the biblical account. Lowly shepherds are present as privileged guards, and glorious angels are present as heavenly choristers. Having identified Him, then we engage our voices to invite all to make haste “to bring Him laud.”

This, this is Christ, the King, Whom shepherds guard and angels sing:

Haste, haste to bring Him laud, The Babe, the Son of Mary!

Stanza 2 (1st half) offers a momentary reference to “mean estate,” or less than an ideal condition. The poet registers similarity with the first stanza with another rhetorical question. He wonders why the Christ child should be displayed in such a humble environment. The second stanza alludes to the anguish and distress of Christ’s future, as well as to His ongoing intercession.

Why lies He in such mean estate, Where ox and ass are feeding?

Good Christian, fear: for sinners here The silent Word is pleading.

Stanza 2 (2nd half) reminds us that there’s much more here than just the sentimental scene of a sweet baby. Dix points us ahead to the cross, since this was the purpose for the incarnation. Dix’s answer to the reason for the “mean estate” under which Christ was born lies in his future suffering on the cross. Possibly Dix knew the Waits’ New Year’s carolmentioned earlier. The second stanza of this carol written over a century earlier also alludes to the suffering of Christ: “His hands and feet were wounded deep, And his blessed side with a spear.”

Nails, spear shall pierce Him through; The cross He bore for me, for you;

Hail, hail the Word made flesh, The babe, the Son of Mary!

Stanza 3 (1st half) Dix expands the emphasis on the people attending the humble scene. He draws inspiration from the Epiphany season and focuses on the metaphorical gifts that are being bought for the infant. His setting flouts the conventional structure of time quite comprehensively, like everyone, stating both the “king” and the “peasant” are offered an equal chance.

So bring Him incense, gold, and myrrh, Come, peasant, king to own Him.

The King of kings salvation brings; Let loving hearts enthrone Him.

Stanza 3 (2nd half) brings the solemn inquiries to an exuberant conclusion by calling one another to lift up a song of praise to the King born in Bethlehem. Here we peek in as “the virgin sings her lullaby,” and respond with the repeated “joy, joy,”

Raise, raise the song on high, the virgin sings her lullaby:

Joy, joy for Christ is born, the babe, the son of Mary.

The GREENSLEEVES tune was already one of the most aesthetic and beloved melodies of the festive season at Dix’s time. Although it’s not a quintessential Christmas tune, its association with the festive season can be dated back to 1642. It was paired back then with Waits’ carol titled, “The Old Year Now Away is Fled.” Also, William Shakespeare refers to this popular tune twice in his famous play, “Merry Wives of Windsor.”

Popular lore says that the infamous King Henry VIII wrote the tune as a love ballad “to my lady Greensleeves.”

Alas my love you do me wrong To cast me off discourteously;

And I have loved you oh so long Delighting in your company.Greensleeves was my delight, Greensleeves my heart of gold

Greensleeves was my heart of joy And who but my lady Greensleeves.

Some sources suggest that the king may have written it for his mistress, Anne Boleyn, who resisted his advances at first. But this great story is probably just a myth, because the musical style of the melody is of an Italian type that reached England after Henry’s death, a style not known to have been imported in England prior to 1550.

In spite of its obscure origins, there was a sudden rush of applications at the Stationers’ Company for licenses related to this tune, starting on 3 September of 1580, with Richard Jones registering “A new Northern Dittye of the Lady Greene Sleeves,” and on the same day Edward White registering “A ballad, being the Ladie Greene Sleeves Answere to Donkyn his frende.” Twelve days later, a religious version was registered as “Greene Sleves moralised to the Scripture, declaring the manifold benefites and blessings of God bestowed on sinful man.” None of these original printings seem to have survived. The oldest surviving printing of a song or ballad intended to be sung to GREENSLEEVES is “A new ballad, declaring the great treason conspired against the young king of Scots … to the tune of Milfield, or els to Greenesleeues,” by William Elderton, registered on May 30, 1581 and printed in London. The original broadside is held by the Society of Antiquaries of London.

The tune was featured more prominently in “A Handefull of Pleasant Delites” (1584), published by the same Richard Jones who had registered his “new Northern Dittye” on September 3, 1580 (this could be the same ditty, but the connection is impossible to prove). This version is text-only, headed “A new Courtly Sonet, of the Lady Green Sleeues. To the new tune of Greensleeues.” The oldest and best example of the melody is usually credited to William Ballet’s lute book, which is a manuscript dated ca. 1590, a piece labeled “greene sleves.” The Ballet version is considered to be the ultimate predecessor for all modern printings of the tune, probably because of the work of William Chappell in transcribing and publishing it in 1840 and 1859.

GREENSLEEVES was famously cited twice in William Shakespeare’s “Merry Wives of Windsor,” written about 1597 and first published in 1602. The quote most interesting to hymn lovers is in Act 2, Scene 1, in which the character Falstaff writes a letter to Mrs. Ford, making an analogy by noting the disparity between PSALM 100 (OLD 100TH) and GREENSLEEVES.

I shall think the worse of fat men, as long as I have an eye to make difference of men’s liking. And yet he would not swear, praised women’s modesty, and gave such orderly and well-behaved reproof to all uncomeliness, that I would have sworn his disposition would have gone to the truth of his words: but they do no more adhere and keep pace together, than the Hundredth Psalm to the tune of Green Sleeves.

GREENSLEEVES was first referenced as a carol tune in Good and True, Fresh and New Christmas Carols (London, 1642) where it was named as the recommended tune for “A Carrol for New-yeares day,” which began “The old yeare now away has fled.”

Here is the carol as sung at King’s College, Cambridge.