“Though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him” (Job 13:15). What kind of faith does it take to hold such strong conviction in the midst of terrible and incomprehensible suffering? When we not only experience the pain of physical misery and the anguish of emotional distress, but also have to deal with the crushing weight of our inability to understand “Why?” Oh, how often does that burden fall upon even the smallest and weakest victims.

As we review history, it’s stunning to realize how common that intense plight has befallen individuals, families, and even nations. It may have been disease or hunger or injustice … or even war. For 21st century Americans, we have been incredibly blessed to live in a time when so many of these tragedies occur in distant lands that we only hear about in the news. Compared to so many places in the world in our day, we have experienced almost nothing of the hardships that have characterized every day of the lives of countless millions of “innocent” victims who have been forced to endure the terrible ravages of war and disease and hunger.

At the time of the writing of this hymn study, the unprovoked war in Ukraine is two weeks old, with growing numbers of incidents of war crimes mounting. Already there have been thousands of deaths on both sides, with 2.5 million – yes, million! – mothers and children fleeing across borders as refugees seeking safety, with more to come, while their fathers and husbands remain to fight off the invaders. And what has been especially horrendous to western eyes has been the indiscriminate, if not intentional, bombings on residential apartments, small businesses, children’s schools, and even a maternity hospital. I am among those who have personal friends in whose homes and churches I have ministered, friends who are today in grave danger.

Certainly a strong lesson we should draw from all this is the reality not only of sin, but also of evil. We rightly compare the actions of Russia’s Vladimir Putin with those of murderous dictators of past generations, men like Adolph Hitler, Josef Stalin, and Pol Pot. And behind all of those is the real enemy, that son of the morning, Lucifer, whose rebellion continues to this day, and will until that moment of Christ’s return. O how we long for that day, when not only will all evil be cast into the pit of hell forever, but also when “every knee will bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Philippians 2:10-11).

So how do we handle the questions that have no answer this side of heaven? Where is God in all of this? Why has He permitted it? How should we respond in faithfulness to Him when we can’t figure it out, or even what we should be doing? The best answer that we have is the biblical response of Proverbs 3:5-6. “Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and do not lean on your own understanding. In all your ways acknowledge Him, and he will make straight your paths.” Yes, trust Him even when we don’t understand what He’s doing, knowing that He is good, that all evil will be punished and all faithfulness will be rewarded, and that an unimaginably glorious kingdom is coming.

How do we sing with that kind of confidence in the face of suffering that we can’t explain? Though there could be many good suggestions, the best hymn that I know is “Whate’er My God Ordains Is Right,” written in 1675 by Samuel Rodigast (1649-1708), born in Groben, Germany just a year after the completion of the Westminster Confession of Faith and Catechisms in England. This hymn should be included in every hymnal and in every Christian’s vocabulary. Even if someone knew nothing of the hymn but that opening phrase, it would be sufficient to qualify as a powerful profession of a faith that is not native to the human heart, but comes only from the supernatural work of the Holy Spirit. And the substance of the assertion of this song is mind-bogglingly powerful and pastorally comforting, when Christians understand it, as only they can.

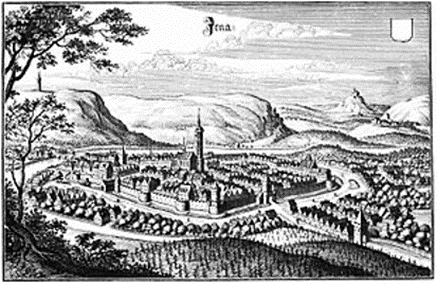

Samuel Rodigast was a German teacher, the son of a Lutheran pastor. He entered the University of Jena in 1668 graduating M.A. 1671, and was in 1676 appointed adjunct of the philosophical faculty. In 1680 he became vice-rector of the Greyfriars Gymnasium at Berlin. While in this position he refused the offers of a professorship at Jena and the Rectorships of the Schools at Stade and Stralsund. Finally, in 1698, he became rector of the Greyfriars Gymnasium, and held this post till his death. He was part of the influential Pietist movement in Germany, a movement that encouraged deep personal devotion to Jesus. It was inspired by Philipp Jakob Spener (1635-1705). (We don’t have a portrait of Rodigast, but attached to this study is a 1650 engraving of the town of Jena where he was when he wrote this hymn.)

The text of the German chorale that Rodigast composed, “Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,” became part of the beloved congregation hymnody in Lutheran churches, and was included among the cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). It was also included as part of the powerful symphonic organ work, “Variations on Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen” (“Weeping, Lamenting, Worrying, Fearing”) written in 1859 by Franz Liszt. It requires significant technical skill and is part of the advanced concert repertoire for organists. The original chorale text is regarded as one of the earliest examples of what became a very sizeable corpus of Pietist hymnody.

Rodigast wrote the hymn while his friend, the cantor Severus Gastorius, whom he knew from school and university, was seriously ill and confined to what he believed would prove to be his deathbed in Jena. When Gastorius recovered, he asked his choir in Jena to sing the hymn each week at his front door! This was to make it better known. It may be that Gastorius wrote the hymn melody and harmony, though proof of that is lacking. But we do know that the music we use has been associated with the text as early as 1690. Before that, the melody with the hymn title had already been used by Johann Pachelbel for an organ partita in 1683.

As with many of the German chorales, the English translation we use was written by Catherine Winkworth (1827-1878). She was the youngest of four daughters in an Anglican manufacturing family. She was never married, never formally educated, and died suddenly when she was only 50, yet her work translating hymns from German to English is indispensable in the tradition of hymn singing today, especially in Lutheran churches. We regularly sing her translations in songs like “Now Thank We All Our God,” “Praise to the Lord, the Almighty,” “From Heaven High I Come to You,” “Soul, Adorn Yourself with Gladness,” and “Jesus, Priceless Treasure.”

Born in London, Winkworth began studying German in her late teens and, molded by her parents’ involvement in her and her sisters’ spiritual upbringing and by private tutors, her study of the German language led her to begin translating German chorale hymns into English. By the mid-19th century, Winkworth’s translations began appearing in English hymnals. She translated nearly 400 German hymns written by more than 170 authors in her lifetime. Aside from translating hymns from German to English, Winkworth spent her life advocating for women’s rights and education, uplifting the poor and impoverished, and writing histories and biographies on German hymnody and hymnwriters.

As we sing this hymn, we are taken back to the account of Abraham who asked, “Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?” And the text grows out of a heart totally secure in the knowledge of the sovereign foreordination of all things by a God who cannot do wrong, even if we cannot perceive it at the moment. This is worlds apart from Islam’s profession of a fatalistic view of God’s control of all things. And it’s certainly far richer and more comforting than a mere sense of resignation, almost a “whatever will be, will be” spirit. No, this is an expression of faith that is profoundly personal, confident that even when I don’t understand what God is doing, He knows exactly what He’s doing at every moment, and it’s all perfect. So I can trust Him!

We have records of six stanzas, though only four of them are generally found in hymnals today. One of the most notable features of the chorale is the repeated statement in the opening line of each stanza, “Whate’er My God Ordains Is Right,” almost as a shout of defiance against the spirit of fear and anxiety that Satan tries to throw like a dark blanket over our hearts in such difficult times.

Stanza 1 points us to the only source of consolation in troubled times: to our God. As we sing, we promise to “be still” as we follow Him where He leads us. And even if that road is dark, we rest in the promise that He will not allow us to fall. The road ahead is the one that will perfectly accomplish His holy will. “Wherefore to Him I leave it all.”

Whate’er my God ordains is right: His holy will abideth;

I will be still whate’er He doth; And follow where He guideth;

He is my God; though dark my road, He holds me that I shall not fall:

Wherefore to Him I leave it all.

Stanza 2 continues the pattern of following wherever He leads us. It may seem a strange path to us, but we know that in His sovereign wisdom it will ultimately prove to be “the proper path,” not only in the sense that He has chosen it, but because He has chosen the path that will best glorify Him. Contentment will enable us to wait for the day when we will see that. Until then we look to Him to turn our griefs away, confident that He will never deceive us.

Whate’er my God ordains is right: He never will deceive me;

He leads me by the proper path: I know He will not leave me.

I take, content, what He hath sent; His hand can turn my griefs away,

And patiently I wait His day.

Stanza 3 enlarges the truth that the God who loves us is trustworthy. The cup He gives us to drink will never contain a poison that could ultimately harm us. It is medicine from our great physician, medicine that will work to cure us from the debilitating effects of sin. Every morning will bring fresh grace to endure even hardships because that grace creates strength within that is not our own.

Whate’er my God ordains is right: His loving thought attends me;

No poison can be in the cup That my physician sends me.

My God is true; each morn anew I’ll trust His grace unending,

My life to Him commending.

Stanza 4 shows more of the honest assessment that the path He’s chosen will not always be easy. But it is the one chosen by the one who is “my friend and Father.” Storms are never pleasant. They bring woe but come into our life along with calm days of joy. These are hard to understand now, but “some day I shall see clearly” that His love was at work in all of it.

Whate’er my God ordains is right: He is my friend and Father;

He suffers naught to do me harm, Though many storms may gather,

Now I may know both joy and woe, Some day I shall see clearly

That He hath loved me dearly.

Stanza 5 goes even further in the honesty of recognizing that there will be times when that cup will seem bitter “to my faint heart.” But if it comes to us in the hand of our loving heavenly Father, we can take it without shrinking, knowing our God would never lie to us. And because of that we find “sweet comfort” for our troubled heart, knowing that “pain and sorrow shall depart.”

Whate’er my God ordains is right: Though now this cup, in drinking,

May bitter seem to my faint heart, I take it, all unshrinking.

My God is true; each morn anew Sweet comfort yet shall fill my heart,

And pain and sorrow shall depart.

Stanza 6 concludes with the solid confidence that enables us to proclaim, “Here shall my stand be taken.” It might be a path of “sorrow, need, or death.” How hard it can be to really believe that in the moment when we face those possibilities. But as we’ve been told in Psalm 23, even in the valley of the shadow of death we will fear no evil, because He is there, holding us that we not fall.

Whate’er my God ordains is right: Here shall my stand be taken;

Though sorrow, need, or death be mine, Yet I am not forsaken.

My Father’s care is round me there; He holds me that I shall not fall:

And so to Him I leave it all.

Here is a recording of the song. There does not appear to be a you tube recording of the original tune, which might be preferred, since it was the one written by Gastorius, the man whose illness prompted Rodigast to write the words. Here the text is sung to a new tune recently composed for it.